Even in the era when newspapers were fat with advertising and therefore dense with real news there were some days there was no space to fit it all in. Sunday, October 21, 1973 was one of those days. US news editors must have struggled with the overload as a look at the front page of the New York Times from that Sunday shows.

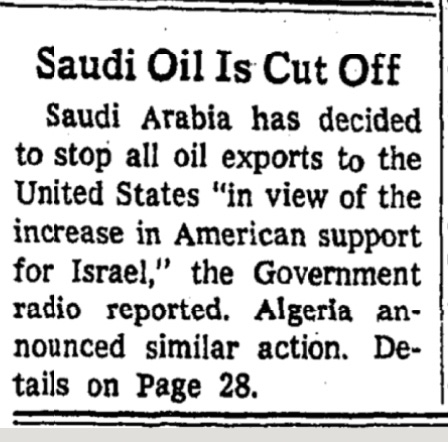

Yet the news that would bring the post-war era to a permanent close was relegated to a box somewhere below the fold.

I wonder how many readers made the jump to page 28, or were so exhausted from reading all the reporting on the Saturday Night Massacre and the on-going war in the Middle East that they simply lacked the energy to read the news in full.

Those who did thumb through the paper to page 28 might have missed the article as it carried no byline and ran a single column long, the page’s other seven columns were filled with a massive advertisement for some Bloomingdale’s hair grooming products aimed at men who were going bald.

The piece datelined Amman, Jordan was based on a monitored radio report from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

“In view of the increase in support for Israel, the Saudi Arabian Kingdom has decided to stop the export of oil to the United States of America for adopting such a stand.”

The move came a day after Libya announced it would no longer export to the US because of its support of Israel. Smaller oil producers in the region also announced cuts.

Of all the historical turning points that would take place that autumn, the Arab Oil Embargo is the one that has had the deepest impact, yet when it was announced the initial response was calm.

Policy-makers seemed to retreat into the safe language of expectations. The coordinated attacks of the Egyptian and Syrian armies on Israel had taken them by surprise. But as soon as they recovered their collective breath the prospect of oil being used as an economic weapon by Arab producers was top of their lists of possible knock-on effects of the war.

Embargos on oil sales had been tried as an economic weapon during the 1967 War and during the Suez crisis. But had been not particularly successful. Unity among Arab nations is always difficult to maintain.

This past history may explain the sanguine conclusions of a CIA report dated October 14, one week after the Yom Kippur war began, on the prospect of oil being used as a weapon.

In the US, the report claimed,

"The impact would not be felt immediately … But Europe and Japan would be seriously affected within three months."

There were stocks in various oil reserves, the report's authors noted. In addition, at any given time, there is a month's supply in tankers already on the high seas.

The report noted, there was ample time to get together a diplomatic strategy to keep European allies united with the US should the embargo really bite. Something that hadn't happened on earlier occasions.

No need to panic is the CIA analyst’s tone.

This prior history must have informed the reporting as representatives of OAPEC, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries, met in Kuwait in the week before Saudi Arabia’s announcement.

"Sign of Arab Moderation in use of oil weapon" was the headline on the first report in The New York Times on October 17th. The story was a 3 paragraph item noting that Gulf oil states were raising the price of crude to $3.65 a barrel or £1.46. Not really that big a price rise.

The CIA report may also have helped to encourage the Nixon administration to get off the fence and choose a side in the Arab-Israel war which had been going on for more than ten days. Israel was slowly clawing back not just territory it had lost in the surprise attack on Yom Kippur but its self confidence. However, its military was fast running out of ammunition and weaponry. On October 19th, Nixon had asked Congress for $2.2 billion worth of arms to be made available to Israel.

Over the next week the oil producers ratcheted up the pressure step by step. The next day's story was: Arabs will cut oil by 5 percent a month every month until Israel withdraws from the occupied territories

The next day Saudi Arabia announced its cut in production.

A week after the first announcement, Libya's Muammar Gaddafi was threatening to deprive Europe of all Arab oil.

By October 26th the flow of oil had been cut by 4 million barrels a day, a reduction of 10 percent globally. Europe with 80 percent of its supplies coming from the Middle East, immediately began to suffer. That big a cut, overnight, even had an impact on the US which relied on the Middle East for only 10% of its oil.

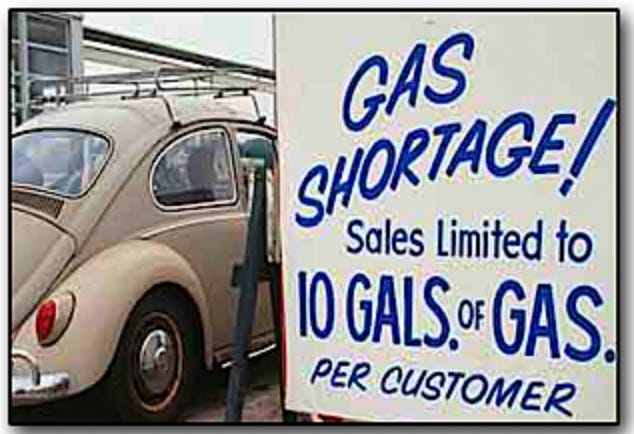

Those sanguine estimates of America's ability to withstand a cutoff of supply were clearly wrong. A little over two weeks after the Oil Embargo got underway stories appeared saying stocks were running low quickly.

It was panic stations on both sides of the Atlantic. A 55-mph speed limit was introduced in the US. Sunday pleasure driving was banned in the Netherlands. The British tabloid, the Daily Mail, then as now looking for the lead lining in any cloud, ran a feature on why Britons' might only be allowed to drive 50 miles a week by Christmas.

Panic buying at American gas stations began.

Panicked public relations gestures were made—officials in the New York area stopped using their limousines.

A quarter-century long economic era of unprecedented prosperity came undone in a matter of weeks.

In the month after the embargo began consumer prices shot up 0.8 percent, the highest jump since the start of the Korean war.

And they would be going higher. American regulators gave airlines permission to bump their airfares up by 5 percent because of the increase in the cost of fuel.

And if things were bad in America, they were worse in Britain.

It was just a month since I had returned to the US from England. My hope was to spend six months back in the US to work at something/anything, save and put aside enough of a stake to return to London to live.

It very quickly became clear that I would not be able to get back any time soon.

Inflation had already been a factor in both the US and UK economies for several years. Now it was accelerating at stupefying speed. At the start of the year in the US, the inflation rate was 3.65 percent, by December it was 8.7 percent. Britain ended the year with a 9.1percent inflation rate. By the end of 1974 the respective numbers would be 10.98 and 16.05, and in 1975, while inflation began to moderate in the US, in Britain inflation would reach an astonishing 24.24 percent.

One reason things were so much worse in Britain was many of its industries were nationalized. The government was big business. Coal, electricity generation, railroads, steel, almost all areas of manufacturing ultimately were owned by the government. The workers in these industries were unionized. In October 1973 the government was Conservative led by Prime Minister Edward Heath. There was a deep, deep antagonism between unions and any Conservative government. The oil shock went to the core of the way British society had been re-organized after the twin shocks of the Great Depression and then the war.

It's not just generals who fight the last war, so do politicians. The men—and they were all men—who were running both the American and British governments' response to the crisis had fought in World War 2. Some had helped organize the post-war architecture for dealing with international economic crises.

Despite being free marketeers they believed that state solutions imposed from central government were the way to prevent extreme economic distortions from creating social upheavals in market economies. Most had grown up in the Great Depression and understood just how extreme distortions could be in capitalist systems. They thought that Wage and Price controls and rationing, were the way to keep things on an even keel. This is the way their economies had worked since the end of World War 2.

And now these solutions turned out to be wholly inadequate. When the Oil Embargo hit, Prime Minister Edward Heath was in the process of rolling out phase 3 of his prices and incomes policy to try and control already existing inflation. The speed with which this new form of inflation accelerated overtook his plans but he tried to press ahead anyway.

And then three weeks after the embargo began, the National Union of Mineworkers turned up. The NUM had already tabled demands for wage increases of 22 to 47 percent during the summer. Now the miners had leverage.

The oil embargo made coal an even more important source of energy in Britain. And here, too, the union leadership misunderstood the new situation and continued to fight the last war—or Britain’s never ending one of the working class against the bosses—only, as I said, the bosses were the government. Heath offered a 13 percent pay increase. THIRTEEN PERCENT!

The union leaders turned it down. The NUM stopped short of striking to get what it wanted. Instead it imposed an overtime ban.

British life quickly veered to the surreal as energy supplies dwindled. Wartime austerity measures returned. Motor fuel ration books were issued.

Not a shot had been fired.

Then in December the NUM announced it would strike.

In response, the Heath government imposed a three day work week on the country.

When I point to October 1973 as a turning point of history and my life, I don't mean there was an instantaneous change of direction, like a train being shunted onto a new track.

It was a subtle shift—no blood was shed in the US or UK—yet it was definitive. In an article published on the last day of 1973, Geoffrey Smith in The Times wrote,

"Suddenly some of the most important assumptions that have gone unchallenged for the past quarter of a century and more no longer look so secure."

In Smith’s words social cohesion, the Social Compact, in which no side would act in a way that would destroy the economy, no longer existed.

But the foundations of the economy no longer existed. In 1972 Western Europe paid a collective $11 billion for imported fuel. As the Autumn of 1973 drew to a close the estimate was that in 1974, European nations would have to pay $50 billion.

There is no way to distribute a price increase of that size rationally. There was no way for wages on either side of the Atlantic to keep up with the inflationary pressures of that increase.

And after a while they didn't.

But it is wrong to understand the impact of the oil shock in spread sheet terms, We live in times where we are not supposed to quarrel with data but social change cannot be simply understood by numbers.

On the same day that Geoffrey Smith published his analysis, Anthony Lewis in the New York Times wrote of living on two distinct levels of consciousness,

"We go about our daily business; we talk about politics, about possessions, about travel and food and football. And all the while it becomes harder to avoid awareness that the ground upon which our society rests is shifting."

The shifting ground: a progressive era with government as the honest broker and referee between business and labour was coming to an end. A transition to a conservative epoch with unregulated markets as the ultimate arbiter of all things was beginning.

One of the by-products of this new age was a revisionist view of the events of Autumn 1973:

No, it wasn't the Arab Oil Embargo that caused the problem, says a paper from Washington's conservative Cato Instititute, The embargo was just gesture politics. Really it was existing price controls that caused the problem by distorting the natural efficiency of the market to allocate and determine prices even in times of crisis.

Historians and economists with this view have some facts at their command: inflation had already begun to afflict the western economies, the Bretton Woods system—a critical piece of that post-War economic architecture—had fallen apart in 1971. The US left the gold standard leading to dollar depreciation. Imports were more expensive, oil denominated in dollars was becoming more expensive for importers—like the UK.

But these problems were being managed—then came October 1973.

A home whose roof has a few tiles that need replacing can manage to survive for many years with minimal repairs and a family can live securely—with the occasional leak—in the house underneath. But if a once in a half-century hurricane blows through, that roof is gone and the house is ruined. The Oil Embargo was a category 5 hurricane.

The fall-out cannot be measured merely in economic terms.

In Britain, as 1973 ended, the three day week went into effect. The miners were on strike. Heath called a general election asking, "Who runs Britain?"

Not you, said the voters. He lost.

18 months later Heath would be ousted as leader of the Conservative party and replaced by Margaret Thatcher. When Mrs. Thatcher became Prime Minister four years later her second order of domestic business—after weaning the British economy from government oversight, and causing another violent contraction in the process—was to destroy the people she called “the enemy within”: the miners and their union.

In America, the political turmoil surrounding Richard Nixon obscured for a time the effect of the Oil Embargo. But following his resignation, his replacement, Gerald Ford is remembered primarily for his hapless WIN campaign, Whip Inflation Now.

Unwhipped, in 1976 Americans voted in Democrat Jimmy Carter to sort things out. He had no luck. Two years after Carter was sworn in, Iran underwent a revolution. The American client regime of the Shah was overthrown by the theocrat Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

This led to another oil crisis and surge in inflation in the United States. The inflation rate for 1979 was 13.3%. The key factor in the consumer price index skyrocketing was gasoline at the pump: up by 52.2%; and home heating oil, which rose by 56.5%.

Carter addressed the nation in July 1979 about energy and oil. He said, "all the legislation in the world can't fix what's wrong with America."

In that speech, known as the malaise speech, Carter also said, "We believed that our Nation's resources were limitless until 1973, when we had to face a growing dependence on foreign oil. These wounds are still very deep. They have never been healed."

In Hampstead, there is a valise in a mansion block flat overlooking Southend Green. It is mine. At least I like to think it is still there even though I know it is not. I left it behind in late September 1973.

The valise contained writing, the best of my undergraduate attempts at fiction and essays. Most of it would be embarrassing to look at today, although in my memory two pieces were quite good. The start of a story, describing a mixed race couple—two young men, at Antioch, who must be in love—you can tell by the way they walk together, in lockstep, their hips and hands brushing. In those days heterosexuals didn't notice those things or write about them lyrically.

There was also an essay I had written taking on the entire English-language philosophical orthodoxy of the time. Logical positivism and ordinary language philosophy be damned, my essay argued that the subjectivity of perception is not a barrier to philosophical certainty. “That’s psychology, not philosophy,” had been my tutor’s condescending response. This led me to the correct subjective perception that I should not pursue a career in the academy.

Also, in this valise was a Kelly green pullover made of mohair, a gift from my not quite ex-girlfriend's parents the previous Christmas. Plus an assortment of basic clothing, probably not well-laundered.

The flat was above a bookstore where, according to a memorial plaque, George Orwell once worked.

I was room sitting for an acquaintance from Antioch. She was off on a month-long jaunt before her year abroad began. The flat was owned by a gay man who rented out rooms to young women. He was a Roddy McDowall'ish character connected to the theatre and very much a mother hen to his tenants. I think he regarded me as a fox in his coop.

The weather was exceptionally fine. The windows were open all day long and a steady pile driving din came through them—a hundred yards up the road the new Royal Free Hospital was under construction.

And the reason I remember all these details half a century later is that the Oil Embargo ended up snapping my life plan in two. These are the memories frozen in time, the before in the before and after moments of an epoch-changing crisis.

My money had run out and I thought I would go back to the US for a while to work, save, and then come back. It was not a crazy idea. Although the pound was very strong against the dollar, the cost of living in England in comparison to America was extraordinarily cheap. And average American wages were nearly double what you could earn in England.

If I could sock away a couple of grand, or just fifteen-hundred bucks, I could afford to rent a place in London for a year while figuring a way around work restrictions on foreigners and getting a career in the theatre going. It wasn’t a complete pipe dream, I knew some people who knew some people.

But the massive inflation in Britain over the next eighteen months meant I needed to save much more money to have a grubstake. It was more than I could earn doing freelance medical writing or other menial work.

Around Christmas, two months after the Oil Embargo began, I had a letter from the classmate in whose room I had stayed. The big valise was in her way and it had to go. Unless I sent her money so she could ship it back she was throwing it out. I didn’t have the money to send her, nor did I have a permanent address where it could be sent.

So it was thrown out. Literally and symbolically, my childish things were put out with the rubbish.

But I was not the only one of victory’s children forced to change my life plans. The effects of the embargo put American society into a transition that would play out for the remainder of the 1970s.

(read on to Chapter Eleven)

And if you need to catch up on earlier chapters, Part 1 of the book , Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here.

Notes:

https://www.nytimes.com/1973/10/20/archives/nixon-asks-22billion-in-emergency-aid-for-israel.html

https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v36/d223

http://inflationdata.com/Inflation/Inflation_Rate/HistoricalInflation.aspx

Wage Politics in Britain: The Rise and Fall of Incomes Policy Since 1945, Peter Dorey, Sussex Academic Press

Super analysis. House mortgages at 18-20%.

Oh boy. In 1974 I had to buy my first car (I had had motorcycles previously) and the 1971 Corolla used cost more than the new price. Also about that time an article promoting the invasion of the Middle East for the oil was published in Harpers. Then there was "Five Days of the Condor" (movie: Three Days..reflecting our shrinking attention spans) where a CIA plot to take the oil was uncovered by intrepid CIA researcher Robert Redford. In this century we have seen how that played out in real life. By the way, another fine piece.