At the end of 1973 the unemployment rate in America was 4.9%, the inflation rate was 8.7% and the economy (GDP) was still growing at 5.6%. A year later, the economy was in its deepest recession since the 1930s.

The economy would return to growth after a few years, inflation subsided then bubbled up again. But for the rest of the decade the unemployment rate would never be as low as its pre-Oil Embargo levels.

The national mood was sour. People went to work, but the relentless suburbanization of the previous two decades meant that most people had to drive to get to their places of employment and gas prices had jumped 43%, and there were shortages. To conserve fuel, a national speed limit of 55 miles per hour was imposed.

Something beyond an economic era in history had ended with the quadrupling of oil prices. The sense of social solidarity that had not only been instrumental in winning World War 2, but had been appealed to throughout the 1960s to advance civil rights, withered quickly. The social democratic goals of the New Deal—although no one involved in planning and delivering them would ever have used the term, “social democrat” in public—were put aside.

The new course on which American society was headed was not clearly marked out but if you looked closely, in two places tied closely to New Deal liberalism, you could discern the path: California and the concrete Eden where I was born, New York City.

Both the New York City fiscal crisis which nearly led the city to bankruptcy and the Proposition 13 tax revolt in California are stories derived from how government is funded: via the bond market and taxes.

Neither bonds nor taxes have the same impact in memory that riots and assassinations do, which may explain why these events don’t resonate in America’s national memory. But stay with me, reader. Bonds and taxes may be dull subjects but the fallout from these events were significant steps along the way to America’s calamity. And I will try to liven up the narrative so you won’t nod off as I explain why.

To begin: the Great Inflation following the October 1973 Oil Embargo was a major factor in both these events.

In New York, the city could no longer finance itself via the bond market. Municipal bonds are how cities and states borrow money to finance infrastructure projects and pay-off previous debts. They are an aid in keeping the tax burden on citizens reasonable.

A paper written 15 years later for the St. Louis Federal reserve explains how the Great Inflation changed financial structures

For nearly 30 years after the Great Depression, the financial

sector experienced an era of relative profitability and little stress.

That began to change in the late 1960s and early 1970s with in-

creases in the level and volatility of the rate of inflation, the advent

of the electronic age and new competition, and the increasing inter-

nationalization of the world's economies.

The average annual rate of inflation rose from less than 2 per-

cent in 1950-65, to about 4.5 percent in 1966-73, to nearly 9.5 per-

cent in 1974-81; in that last period the rate was also very volatile,

ranging from about 6 percent to almost 14 percent. As the level

and volatility of inflation increased, so did the level and volatility

of interest rates. Faced with higher levels of inflation, lenders de-

manded higher interest rates, since the dollars with which they

would be repaid in the future would be able to purchase less than

the dollars they were lending.

The bonds, regarded as safe and secure, were the foundation of many retirement portfolios—personal and institutional. In 1973, New York City municipal bonds might pay 5% interest twice a year. But with inflation suddenly running to double digits those returns meant investors were losing money. As inflation had spiked, the market for municipal bonds collapsed. But the City’s obligations were ongoing and considerable. It needed to continue to borrow to meet them.

In the decade prior to October 1973, the suburbanization process which saw families like mine leave the city began to hit New York’s business community. A thousand businesses a year were leaving, taking with them jobs and tax revenue and leaving behind workers who needed public assistance as they looked for new employment, employment that was increasingly difficult to find.

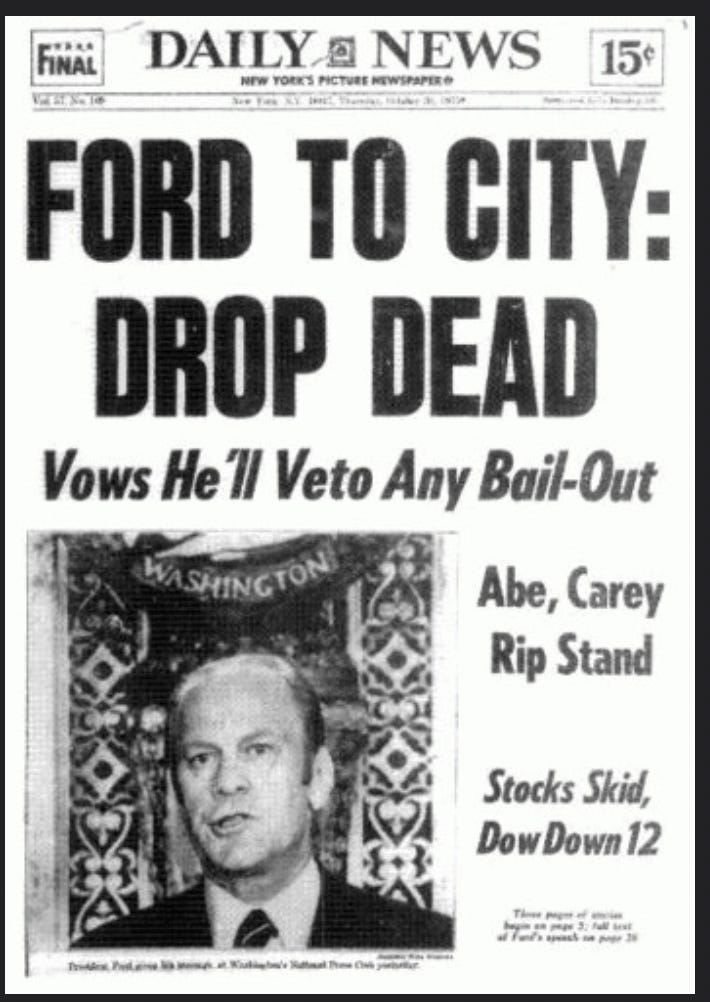

But even with the underlying economic conditions, access to credit should not have been impossible. New York City was the financial capital of not just America but the West—the “free world”—locked in a Cold War struggle with Soviet communism. The idea that the capital city’s government might default on all its obligations should have been unthinkable. But the federal government was willing to think it, hence the Daily News’ front page. The city’s business elites were also willing to think it and even allow it to happen, unless they were brought in to restructure the City’s finances and re-direct its’ government’s goals.

A terrible game of brinkmanship went on as the city began to cut services and defer maintenance of infrastructure. Crime increased. New Yorkers’ civic pride, which often seems like arrogance to outsiders, was not marshalled to stop the city’s physical decline.

Starting with the events of October 1973 and the Oil Embargo, a financial crisis boiled up. New York needed to borrow heavily to cover pension payments to its city work force as well as other normal operating expenses. But like a business that was going bad, city government had for years cooked the books. It claimed future anticipated revenues that went beyond optimistic into the realms of fantasy. Money set aside for long term capital expenditure had been used to cover day to day operating expenditure.

Inflation hit the city’s unionized work force. Instead of inflation-linked raises they were told there would be wage freezes and lay-offs. Wildcat strikes followed.

The Governor of New York, Hugh Carey, and the new Mayor, Abe Beame, a former accountant, as well as some people deputized from Wall St. looked for a way to head off the fiscal crisis. Over the summer of 1975 the city had obligations totaling nearly $3 billion due and no way to pay them.

In the spring of 1975, a rescue plan was hatched by a group led by Felix Rohatyn, a partner at venerable investment bank, Lazard Freres. A new non-profit entity, the Mutual Assistance Corporation known as MAC, was set up so that New York State could lend New York City money. The quid pro quo for loans from the MAC was surrender of much of the city’s authority over its budget despite the fact that much of the funding to start the MAC came from the pension funds of municipal employees’ unions. In addition to funding the rescue operation, union leaders agreed to a twenty percent reduction in the City’s work force: a total of 50,000 jobs would go.

New York City became the trial run for the policy called in the 21st century, “austerity.”

The fiscal crisis would ease over time, but the city and those of us who lived there would pay a price.

Seventeen years after I had been exiled from the city of my birth, I had returned to New York to work as an actor. I arrived in late August 1975 shortly after Martin Scorsese wrapped filming on Taxi Driver and about two months before Gerald Ford told the city to drop dead.

I moved onto east 12th street, the street whose life is depicted in Scorsese’s film. The pimp, played by Harvey Keitel in Taxi Driver, oversaw the prostitutes working the corner of Third Avenue and 12th Street from a little portico just a few yards in from the corner. Keitel’s hair and costume were a direct copy of the pimp’s. The star of his stable was a pubescent girl who couldn’t have been more than 14, just like the Jodie Foster character. I watched her age three decades in the three years I lived on the block. The needle tracks sprouting on her arms, her face growing puffy with alcohol and occasional beatings. No one from city services or even the police intervened. Indeed the cops were rarely seen on the block.

Like most wannabe actors I had to do something else to make rent while confidently waiting for the break that would make me, if not a star, at least a well-known jobbing actor. The choice was between waiting table or driving a cab. I hate standing up for hours at a time and love driving, so I chose the cab and signed up for the night shift at Dover Garage on Hudson St. in the West Village.

Every driving shift contained triggers for a reverie, reconnecting me to the early life I had lived and never wanted to leave.

Coming back from Queens on the 59th St Bridge I always looked for the ambulance elevator down to Roosevelt Island, Welfare Island as my parents called it. Metropolitan Hospital used to be there. It was where they met. My father was a resident in Obstetrics and Gynecology and my mother was a dietitian. Every time we drove over the bridge, one or the other of them would point it out.

“The night you were born, Mike, we rode down to the hospital in that elevator.”

The words spoken while the burnt sugar smell of bread being baked at the Silvercup building came through the car windows.

Any corner, any street had a memory.

The intersection of 80th and Madison Avenue. On the northeast side of the street was PS 6, my elementary school. On the north west side, Frank Campbell’s Funeral Home. Everytime I passed through that intersection a vivid memory of looking out the window of my first grade classroom at the crowds blanketing the intersection the day of bandleader Jimmy Dorsey’s funeral at Campbell’s popped into my head.

Trapped on Seventh Avenue and 31st Street at rush hour, a regular occurrence, images of my Uncle Charlie and Uncle Lou in their work spaces in the garment and fur businesses located in the vicinity were as vivid in my line of sight as the stalled traffic and the Hispanic and Black guys pushing racks of clothes along the sidewalks and between cars.

But the ghost from the life I had almost lived who accompanied me everywhere was my grandfather, dead that same autumn of 1973 when the world changed.

“Do you work the Bronx?” guys at shape-up would ask each other. People at downtown parties would ask me the same question. The Bronx, the city’s only borough on the mainland of the United States, was going up in flames. Cabbies were getting robbed and killed up there.

“Work anywhere,” I would reply. But especially the Bronx. Because it is where all my beloveds—grandparents and aunts and uncles—had lived.

My paternal grandfather was born into terrible poverty in 1896 in a tenement underneath the Manhattan Bridge on one of the worst streets on New York’s Lower East Side. He was the youngest son in a family of six and ended up supporting everyone.

He pulled himself out of that poverty by his own will power and became a dentist. He did well, built a nice middle-class practice in the Bronx. The Great Depression didn’t hurt him as much as it hurt others. People always need their teeth fixed. He had cash flow when most didn’t.

Growing up, there was no person on earth I loved more than my grandfather. Everyone loved him. He was easy-going and generous and supported a large extended family. He never asked for anything back. He was happy he made enough of living to help. It was a personal thing but it mirrored in many ways New York in its era of mid-20th century greatness. It was a manufacturing center and predominantly working class immigrant city with a simple social democratic governing ethos. Those who have help take care of those who don’t.

By the time I started driving the cab my grandfather was dead and the rest of my family had left the Bronx. They had retired to Florida but maybe before they were ready to go.

And the reason for their early departure was the city was at war with itself and the frontline was the Bronx and one of the major areas of engagement was the very street where my grandfather had his dental office: Bathgate Avenue

I was working uptown in Manhattan, a warm Sunday afternoon, and got flagged down and taken to an address somewhere under the elevated train on Jerome Avenue in the Bronx. It wasn’t eight blocks to where my grandparents’ apartment had been.

I had heard things had changed in the five years since they had left. When I told one garage wise guy about my family’s connections to the neighbourhood, the man said, you don’t want to go there. But like a child at his first open-coffin funeral I just had to sneak past the adults to see what a corpse looked like.

The corpse was my childhood.

Nothing, not one single thing was left as it had been on my last visit five years earlier.

A neighbourhood that was mostly Jewish and Irish had in under five years become almost completely Black and Hispanic. On Burnside Avenue, the local shopping street, all the businesses had changed hands.

The Garden bakery, which had the best rye bread and challah in the world, cheese Danish to die for, was now the Muslim no. 3 bakery run by the Nation of Islam, the Black Muslims. The Orthodox synagogue next door to my grandparents’ apartment building was now a Spanish Pentecostal church.

The barber shop, the hole in the wall pizza place … gone. Gone in no time.

White flight at warp speed.

But what was as shocking as the sudden disappearance of white faces was how the streetscape had changed from one of middle class tidiness to poverty’s landscape: uncollected rubbish blowing along the sidewalk and rolling into the street, pedestrian faces sullen from a daily grind without hope.

Back at the garage, another shape-up, I told the wise guy about my journey through the past. “You are a glutton for punishment.” he snorted.

A few months later in the dark of winter, a Saturday evening up by the George Washington Bridge, trying to work my way downtown to where the money is. The Saturday rush hour of people heading to restaurants, theatre, parties, is well under way. Cruise towards the great teaching hospital complex at 168th and Broadway. The temperature in the teens fahrenheit and just outside Columbia Presbyterian Hospital a young woman steps half into the street to flag me down.

A cab driver processes a lot of visual information into economic decisions in under a second. What I processed, looking at this person illuminated by the pink glare of halogen street light was: not a woman, maybe 16, not more than 18, Black, holding bundle in front of her, bundle clearly a newborn infant, must be since she’s in front of hospital, not dressed properly for the cold. Alone, why alone? Going home with baby. Will be going to Harlem or Bronx. Will not have much money. Keep going.

A thought overrode the data processed conclusion. An illustration from a Dickens novel, fallen girl, alone on the highway, needing mercy.

I stopped. She got in. Gave me an address in the Bronx.

“Can you show me where?” She nodded.

We drove in silence off the island of Manhattan, over the Harlem River and into the borough, towards the Grand Concourse.

It really is a grand boulevard, the Concourse, modeled on the Champs Elysees, although instead of the Arc de Triomphe at one end and the Place de la Concorde at the other, it has Yankee Stadium and Loews Paradise movie theatre. The Bronx is a place of the people and for the “people.”

The bulk of it was developed in the 1920’s and 30’s after the subway arrived, connecting the area to jobs in Manhattan. The Concourse and the streets close by were covered in glorious art deco apartment buildings. My grandparents lived in one.

The Bronx is quite hilly and the Concourse runs along a ridge and either side the streets slope away quickly. The girl told me to turn off the boulevard and head down one of the eastern sloping streets.

Into the urban valley of death we rode. Only a few of the street lights worked, many of the apartment buildings seemed to be completely empty.

I made eye-contact with her through the rear-view mirror. God, she was young. There was no affect in her face: neither listless, nor sad, nor angry, eyes alert but no further outward show of energy. The infant was stuffed inside her cheap parka, asleep, a bit of face and clenched fist showing. She was going home. To what? To whom?

The buildings were abandoned or seemed to be. Darkness in the houses on this grim black night.

“Here is good.”

A triangular intersection, the middle of nowhere, too cold for a soul to be in the street.

A tiny voice. “I haven’t got any money.”

“I didn’t think you did.”

She slid out. I should have made my way back up the slope to the Concourse but I didn’t. Instead of filling my pockets with Saturday night tips working the Upper East Side of Manhattan, I went deeper into the Bronx. I cruised a few blocks and found myself at Crotona Park, 127 acres of grass and trees in the middle of one of the most densely populated areas in America.

I drove up a hill to the park’s northside. Middle class apartment buildings overlooked the park. Well, middle-class no more. Several were abandoned. Scorch marks from the fires that emptied them scarred the brick work. People were living in one burnt out shell. They had built an open fire in the living room and I stopped and looked up at their coming and going in the flickering light. In other abandoned buildings you could see the same thing. Life going on in the rubble, like a photo of Berlin after the war.

Crotona Park was a few blocks away from Bathgate Avenue where my grandfather’s office had been. I had come this far and had to go the rest of the way.

I saw nothing recognizable. Burnt store fronts, no people. Wreckage.

Somewhere on one of these blocks my grandfather had practiced dentistry. For 30 years he had left his apartment and walked the mile and a half to Bathgate Avenue, seen patients all day, and walked home again. The neighbourhood had begun to change in the 60’s, the children of his Jewish/Irish/Italian clientele had moved to the suburbs. Puerto Ricans and African-Americans moved in. He stayed.

One day in 1970, shortly after the last Passover Seder my family celebrated in my grandparents’ apartment, he got mugged in his office. He went back to work the next day. A few weeks later he got mugged again. He was 74 years old and my father and uncle said, Enough, Pop. He and my grandmother were in Florida within months.

One story, but even if it was multiplied a hundred times a year in this small section of the city it still shouldn’t have amounted to this devastation.

Something terrible had been allowed to happen here. Why? How could its leaders allow a huge section of this city to be reduced to rubble—as if it had been on the receiving end of a night raid by the Luftwaffe in 1940?

And it wasn’t just the Bronx.

Another bitter cold night, another hospital, Beth Israel, First Avenue and 15th Street. Past midnight. A woman under streetlight hailing a cab. Process info: middle-aged, Black, white uniform peaking out under hem of winter coat, white shoes, bone-tired face, nurse coming off shift. Economic decision: pick her up.

She got in and closed the door then said, Brooklyn. Can you show me where? Yes. Which bridge? Brooklyn Bridge. We went over the great span.

“Now where?”

“Just go along Atlantic Avenue.” And so I did. Deeper and deeper into Brooklyn. She dozed. Wake her up.

“Going in the right direction?”

“Keep going.”

It was the same thing as the Bronx. Street lights not working, buildings abandoned, scorch marks licking up their sides.

We came to a neighbourhood called East New York, turned down a couple of side streets and were in the middle of several square blocks of burnt out half-standing apartment houses. Only one was still in tact. A few of its windows had lights on hinting at occupancy.

“Here,” the woman said.

Whatever the fare was I don’t remember but I do remember she was a quarter short. “Can you find your way back?”

“Yes.”

Quickly head back towards Atlantic Avenue. Stopped at a red light, a couple of young men walk past. They processed their visual information. Their conclusion was written on their faces. An alien has landed: White cab driver, 1 a.m. in East New York. Citizens of the same city, as strange to each other as visitors from another planet.

My grandfather was a wonderful, generous man, he made a good living and took care of all his family when they had tough times. New York until a few years earlier had done the same, taken care of its own when times were tough and now it was no longer doing that.

Why? Driving back along Atlantic Avenue to the garage, done for the night. Why?

For the city to reach this state and then to settle on austerity policies as a way to extricate itself from the crisis required a particular mindset among its policy makers. An idea that was discussed among them was the idea of “planned shrinkage”, getting the population numbers down by withholding government services in certain areas.

We could simply accept the fact that the city’s population is going to shrink, and could cut back on city services accordingly, realizing considerable savings in the process.

That was how Roger Starr summarized the idea of planned shrinkage in November 1976 in the New York Times Magazine. Starr was the city’s Administrator for Housing and Development. His was an official voice advocating for a policy that wasn’t official but had been around for a few years.

In the late 60’s the Rand Corporation’s New York office began looking at the problem of increasing fires in the city. Rand was notorious as a defense think tank that provided the cold numerical calculations for some disastrous policy decisions on Vietnam. It’s founder Herman Kahn was allegedly the model for Dr. Strangelove.

In 1971 as the city’s slide towards bankruptcy was well and truly underway, the Mayor at the time, John V. Lindsay, approached the Rand guys to help him find a few million in savings from the fire department budget. They crunched the numbers on response time to initial reports of fires and created an equation that found 40 fire stations around the city could be closed. By a not so amazing coincidence these 40 stations were mostly in poor neighbourhoods whose net contributions to the city’s coffers in tax revenue were low. Where the stations closed, the city burned.

If numbers were the only inputs to use in making these decisions then the quants at Rand crunched the wrong ones. At precisely the time they were doing their studies— the half decade from the late 60’s to early 70’s—New York City was losing 600,000 manufacturing jobs, 1/6th of all jobs in the city. It was a long term trend accelerated by the Oil Crisis. In the same period of time, a quarter of the city’s white middle-class residents moved out, while there was an almost equal increase in the city’s black and Hispanic population. It was these newcomers, who had migrated to the city to work in industry just as New York was losing its manufacturing base, whose neighbourhoods were burning.

The manufacturing job losses showed New York was no longer a working class city, a rough democracy where the little guy’s experiential wisdom counted as much as a Yale-educated guy’s theoretical wisdom. Roger Starr had attended Yale, and thought that managing the decline of the city was the only way forward. That meant moving poor people out. A decade before his New York Times Magazine article appeared Starr had written:

“American communities can be disassembled and reconstituted elsewhere about as readily as freight trains.”

Move the poorer communities out, resettle them elsewhere.

And now, as the very areas where fire companies had been shut down burned, Starr, wrote in the New York Times it was

“Time for all New Yorkers to recognize that the golden door to full-participation in American life and the American economy is no longer to be found in New York.”

During my time in the cab some fire companies in the Bronx were fighting twenty fires a day. That’s 7,300 a year.

Arson was alleged to be the cause of most of them but recent research has shown that fewer than ten percent of the fires were set by vandals or landlords trying to get insurance money. The more common reason buildings burned: Fire inspections were down by 70 percent as a result of budget cuts, fire call boxes weren’t maintained for the same reason.

Planned shrinkage began to work. In the south Bronx some districts lost 90 percent of their residents in less than half a decade.

Throughout 1977 the reality of New York life made it seem as if some deity was trying to encourage people to leave - planned shrinkage as dictated from Olympus.

On July 13, at twilight, the streetlights began to flicker and then surge bright and then the whole city went dark. Blackout. Within minutes rioting began in a Brooklyn area that had seen services withdrawn: Bushwick. People surged towards the shopping streets, emptied stores of their goods and then torched them.

When the New York Yankees reached the world series that autumn a helicopter shot of Yankee Stadium showed a large fire a mile away. The millions who had tuned in to watch a baseball game got to see the grim reality of the city instead.

Planned shrinkage was never an official policy or a law. Later in his life, after he had left his job as the city’s housing administrator, and become an editorial writer for the New York Times and a founding father of what would come to be called neo-Conservatism, Roger Starr expressed regret at coining the term.

But withholding fire and policing services to New York’s poorest did have the expected effect: New York lost nearly 10% of its population in the 70’s. Most of that loss came from the neighbourhoods burnt out by official neglect.

The Great Inflation undid the New Deal ethos of the Democratic Party not just in New York City but around the country. Government services began to cost more, primarily because government workers needed to earn more to keep up with rising prices. To pay for those increases meant raising taxes which was politically a less and less viable option.

Democratic political leaders from Presidential hopefuls through governors became advocates for cutting deficits despite persistent unemployment. The core New Deal economic policy—spend in times of recession to get people jobs—was put aside.

The 1973 Oil Shock recession inevitably saw a spike in unemployment. The number of people out of work nearly doubled, from 4.6% to 9%. But this time around, unlike the 1930s, there was no rush by the Federal government to ease that shock. Nor was there a rush at the state level and, as the New York City example demonstrated, at the local level either.

A neat forty years after Franklin Roosevelt was sworn in as President, the biggest downturn since the Great Depression showed that the sense of solidarity and government purpose that helped beat back that catastrophe no longer existed.

Race played some part in this. Government programs, particularly Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs were seen to benefit racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately.

But the pushback against taxes was more about crude, individual economic self-interest. That is the origin of California’s Proposition 13 ballot initiative, which sought to limit property taxes.

Proposition 13 came directly out of the Great Inflation. As inflation fed through into the property market, tax assessments started going up dramatically. Elderly home-owners, many living on fixed incomes, struggled to pay the increased property tax rate.

In California, education was funded by property taxes and here is where racism may have had some influence. Some people resented the fact that their rising property taxes went to fund schools where students might be children of illegal Mexican migrants but for most supporters of the initiative it really was about cutting tax, nothing else.

Proposition 13 set a cap of 1% on the rate of property tax. The proposition also required any future increase in state income or sales tax to be passed in both houses of the California legislature by a 2/3rds majority, a very high hurdle.

The initiative was put to a referendum vote in June 1978, nearly 2/3rds of California’s voters took part. Proposition 13 passed in a landlside.

The result was immediate. Property tax revenue dropped by 60%. The funding for education declined rapidly. From having one of the best public education systems in the country, California’s ranking fell quickly. Class sizes mushroomed, summer schools were shut down, school library hours shortened, basic maintenance of buildings was delayed.

Today the state languishes near the bottom of the 50 states on most measures of educational attainment.

The Proposition 13 victory was an important signpost on the path to calamity. It represented a giant step away from the idea that education was a public good that needed to be funded generously and should not be politicized.

But it also confirmed for professional politicians of both parties that in a time of extreme inflation people were not willing to pay more taxes to maintain public services or fund welfare programs for those who needed a boost up. The New Deal era was over. The plug had been pulled in response to October 1973 and the Great Inflation which followed.

In New York, pushing the cab around the city, waiting for my big acting break, Proposition 13 was a noise off-stage. Many of the other events of the last half of the 1970s passed me by. In this I was not much different than most other Children of Victory.

When the oil shock hit and the great inflation set in, the response was not a progressive one.

What isn't understood or remarked on enough—because it is more anecdotal than data backed—is that the great cultural paradigm shift that occurred in the 1960s was the result of a remarkable coalition of two kinds of radicalism: lifestyle and political.

For a few years the two were harnessed. Liberation could be about sex or it could be about undoing racial segregation.

Radicalism could be about smoking marijuana as an act of civil disobedience or it could be about forcing your own government to end a war it was prosecuting.

But as the Vietnam war wound down, and the government started firing live rounds at student protestors, the lifestyle/political radical coalition started fragmenting.

When the great inflation set in the split more or less became total. The need to earn a living would have come to all in my segment of the post-war demographic bulge but how much people had to earn was going up and up as they tried to keep pace with the cost of living.

What price principles in an age of runaway inflation?

The world where you could hold back and say, No, to business as usual was built on the same cheap energy as the post-war economic boom.

One of the greatest powers of the Anglo-American version of capitalism is its ability to commodify anything. Lifestyle became a commodity, something that could be sold back to people.

Woodstock Generation? At Woodstock, the fences had been knocked down and the festival became a three-day long free concert. People of all sizes and shapes took drugs, danced naked and fornicated in the mud. That was 1969.

By 1977, Studio 54 had replaced the ideal of Woodstock. There wasn't a fence, there was a velvet rope. Wannabes desperately queued for hours hoping they were pretty enough to be selected to get inside, where beautiful people took drugs, danced naked and fornicated in the balcony.

And it was certainly not free. "We make more money than the Mafia," the club's owner, Steve Rubell, reputedly said.

The poorest parts of New York were burning down while the party went on at Studio. There was howling among political radicals, but to no effect. The lifestyle party was in full swing, and it cost good money to join in. Drugs cost money, having your hair styled cost money. The partygoers tuned out the politics.

While people danced or read about celebrities in People Magazine, which was launched around this time, a great population shift from Detroit and other industrial cities was going on. It was every bit as devastating as the migration out of the Great Plains during the Dust Bowl years of the Depression. By the time it was over the Rust Belt cities would lose 40 percent of their population.

No John Steinbeck recorded this in the hopes of rousing people to action—although Bruce Springsteen told the story in songs and sold millions of records and filled up global stadia singing them. The disconnection between the intentions of his work and its commodification is something he has spoken of as he has grown older, in his plain way.

But for the most part, people who had gone into the streets to protest the Vietnam War, were untroubled by the economic disintegration inaugurated in October 1973.

The memory of pulling together through depression and war turned to an autumn mist and then burnt away.

Individuals made their accommodation with the economic and political reality that had come into being. Progressive politics reflected the coming age of conservative individualism. It fragmented, with many people devoting themselves to single issues, fighting for narrow causes that would benefit them alone.

I grew up taking part in political demonstrations that changed history. As a journalist I have covered conflicts whose origins are in centuries old history, and wars that will still be effecting history a century from now. I have also lived long enough to have acquired a fair amount of personal history.

What I’ve learned is that for all the politics and ideologies and massacres the greatest force driving history is each individual's realization that they will only live this one life, and either they seek to change the world or accept it as it is.

The effects of October 1973 lead to the Great Inflation and it took the rest of the decade for people to accept that there would be no going back to the time before. The Children of Victory accepted the situation.

As the 1970s ended, the Age of Reaction, the foundation on which America’s calamity would be built, was about to begin.

This is the fifth and final chapter in part 2 of History of a Calamity, October 1973, which begins here. If you like what you’ve been reading, please make a donation.

And if you need to catch up on earlier chapters, Part 1 of the book , Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here.

Part 3, of History of a Calamity, “It’s a Hack’s Life”, will be published chapter by chapter in the month’s ahead:

“Journalism is a calling, gathering news and information is what we do. People value the information we report and journalists need to be paid, so the news became a business. And in the difference between a calling and a business is the tension and destructive force that news media has become on America’s march to calamity. Sadly, this has occurred during the decades I have spent working as a reporter, a hack.”

Notes:

https://www.multpl.com/inflation/table/by-month

https://www.thebalance.com/unemployment-rate-by-year-3305506

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/ERP/pages/6688_1990-1994.pdf

https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/why-the-bronx-really-burned/

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-inflation#opportunity

https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1242&context=jssw

https://capitalandmain.com/taxpayers-remorse-the-life-and-times-of-proposition-13-0729

https://cdha.cuny.edu/coverage/coverage/show/id/33

p.10 in above

The history matters aside (I remember people saving that issue of the Daily News), I am struck by your memories of individuals that you encountered as a cab driver. In very different contexts, archivist, librarian, bookseller, and residence hall director, I had interactions that, while not particularly dramatic, have stuck with me. (I seem to have quite a few of those and I am not sure what that says about my life.) The people you have described in this issue and others in the series are drawn vividly with me wondering what ever happened to them, too. I am looking forward to future stories.

Thanks, Rip. These memories have accrued like barnacles on the inside of my skull. I tell myself that if I could make these things up I could be a novelist ... but I can't. So I'm a historian and memoirist.