CHAPTER FOURTEEN: IS GOD PUNISHING US?

Part Three of History of a Calamity: It's a Hack's Life

When you prepare to move on from the city of your birth, the place where you have made your adult life, every moment is filled with doubt. Emigration is an act of despair as much as hope. You spend your time cutting for sign, making sure the new track you are about to set out on is the right one.

Or maybe you get a sign from heaven.

The third week of November 1985. I was a newlywed, emigrating to London on the strength of my wife’s passport, wedding largesse from family and friends, and two letters of introduction to editors at liberal publications in Britain.

My wife was already in London looking for a flat and I was sitting immobile in her New York apartment at the corner of First Avenue and Second Street, amid suitcases and the detritus of departure. My left ankle encased in a plaster cast.

The day before I was supposed to fly out to meet her I had gone for one last jog along the East River Promenade. I ran down Houston Street to the river, not quite a mile away, full of good spirits, a new life in prospect, a chance to start over at 35—a gift. Turned north at the river and glided along gthe promenade for a half mile then turned back for home. Ahead was a pile of neatly raked leaves. I felt giddy as a five year old and ran straight for it. The leaves were covering a pothole about a foot and half deep. My left leg went into it at jogging speed. My foot curled in and my ankle twisted. I lay on my back for a while laughing at my stupidity and gasping in pain. After a few minutes I remembered what city I was in and where I was: Loisaida, Alphabet City looking at the Jacob Riis housing project which was called Little Saigon by the police.

Lying like Gregor Samsa on my back, I was aware that I would very likely get squashed if I didn’t get up and out.

The ankle wasn’t broken but the ligament and muscle around the joint had been turned to spaghetti. Surgery wasn’t an option as my wife was waiting for me in London so the doctor encased it in plaster.

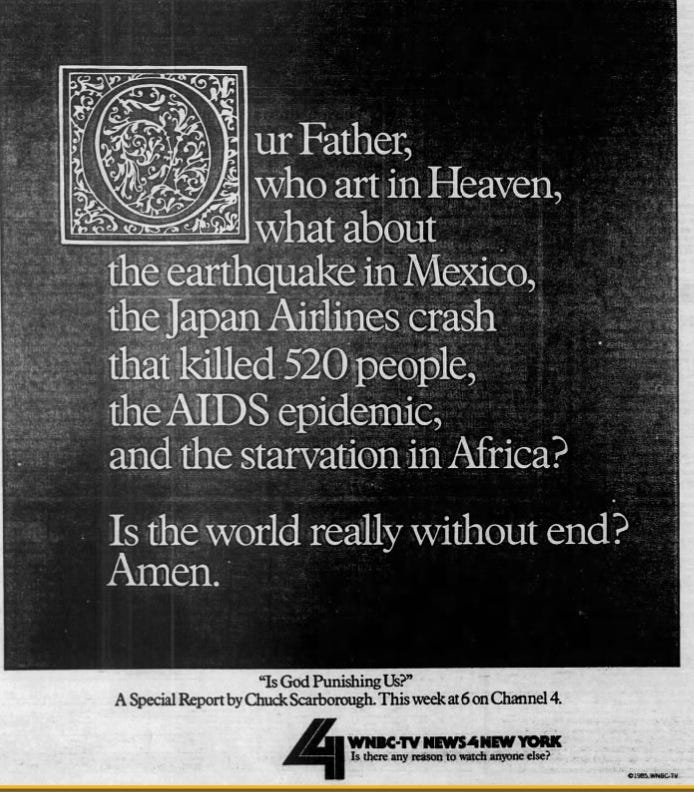

My departure was delayed for ten days and I passed them finishing an article and watching TV. There was plenty of time for doubt to come into my head about this move. But then came the sign that I had taken the correct turning. WNBC’s local 6 o’clock news started a series that week called, “Is God Punishing Us?”

1985, like many of our recent 21st-century years, was a time of one disaster after another. AIDS deaths were up by more than 30 percent. Rock Hudson had just died of the disease. 20,000 people had just been buried in a mudslide following a volcanic eruption in Colombia, an earthquake had killed 10,000 people in Mexico City a few months earlier. Hurricane Gloria, the biggest in two decades, had just blown through New York. Add in the Ethiopian famine, the Japan Airline crash that killed 520 people:

“Coincidence?” WNBC wanted to know, or, “Is God Punishing Us?” That was the title of the series.

That was not a question native New Yorkers were asking themselves at that moment and I speak as a native, born in New York in the numerical middle of the American Century. After my father’s career took us to the Philadelphia suburbs when I was a boy I had moved heaven and earth to get back to Manhattan as an adult.

It was exactly ten years since I had returned to the city and begun my wildly unsuccessful career as an actor, moving into an apartment on 12th Street between Second and Third Avenues (see chapter 11).

Ten years earlier my block was a place to be honorably poor. Manhattan intellectual life still had space for that concept then. Whether they were involved in it or not, people understood the risks of the artistic life. You could be possessed of greatness and still die penniless and unknown. There was respect given for choosing the harder path.

And everything seemed possible. One college friend had just become the first woman hired to shoot local television news, another had become the first woman sound technician in her union. They worked for WNBC. On days I wasn’t driving a cab I watched their stuff. Local TV news then was like reading a crusading tabloid newspaper. The news for the most part was hard, chat was at a minimum.

Many of the reporters and editors had in fact started out at the city’s tabloids. The reporters’ names won’t mean much today but I will write them down anyway: Gabe Pressman and John Johnson are just two. Another was Victor Riesel, a commentator on Channel 11’s news. Riesel had been a labor correspondent for the Daily Mirror, a New York tabloid long defunct. (Yes, there was a time when covering unions and the world of work was a full-time beat in American journalism.) Riesel had been working on an exposé of mafia infuence in unions back in the 50s when a hit man blinded him by flinging acid in his face.

Local TV news, my block, my dreams represented a mid-century liberalism that now belongs to history.

East Twelfth Street in 1975 was that rarest thing in America’s physical and social geography: a place where different classes, ethnicities and ages lived in an approximate sense of economic equality. Old, young, Puerto Rican, Irish, Jewish, Black, Italian, from the suburbs, or whatever our place of origin we were all roughly in the same economic boat at that moment: broke or nearly there.

Only rarely in American history is there a time and place for this kind of social interchange. The armed forces in the Second World War was a place where social structures were broken down (except for African American soldiers). The middle of that often maligned decade, the ’70s, in New York’s East Village was another.

But now, ten years later preparing to depart, Twelfth Street was closed to me. The prostitutes had been moved on and NYU built a dorm on the vacant lot adjacent to my building where they used to turn tricks in an abandoned Citroen 2CV. Over the years, I had been forced further and further east by gentrification, deep into Alphabet City or Loisaida as the neighbourhood was called by its Hispanic population. I eventually landed on Seventh Street between C & D.

To the west to the north to the south, blocks of abandoned buildings hovered over rubble filled lots where arson had done its worst. To the east was the Jacob Riis housing project. The nights were frequently punctuated by gunfire from its gloomy precincts which is why the cops called the place Little Saigon. No one knew, and except for maybe the Village Voice, no one in the mainstream media cared. Arson, drugs—by 1985 it was an old story.

The neighborhood suffered from not so benign neglect.

“Is God Punishing Us?” Biblically, the better question would have been, “Is God Abandoning Us?” Loisaida had surely been abandoned by the city’s goverment and the government’s real bosses, the banks, who held New York’s still massive debts. And yet, the community remained. People squatted the abandoned buildings, most of them were not crazy, just resourceful. Some homesteaded. My roommates had put sweat equity into saving a building the city had taken over, in all likelihood because the landlord had stopped paying property taxes. They had earned a stake in its ownership.

The street was alive. Halfway to Tompkins Square, the sheriff of 7th Street kept eternal watch on the block seated on a folding bridge chair outside his church, an Hispanic pentecostal congregation. We nodded to each other, made pleasant conversation, exchanged gossip about crime.

Weird things happened. One summer the short, round, bottle people turned up. They spoke with a Spanish accent I had never heard before and have never heard since. By day they roamed the city collecting bottles for their return deposit value—hundreds and hundreds of them. By night they set up a little encampment just past an abandoned bodega at the corner of 7th and C, grilled their dinner, slept on the pavement. They opened up a fire hydrant to bathe. After a week or so they began dragging sheets of corrugated tin to the encampment and began building a favela in a vacant lot. When the favela got too big the police arrived and the short, round bottle people disappeared.

I don’t tell these stories out of nostalgia. The City changes, that’s a given. But why the City changes is forgotten and some things should be remembered.

By 1985 things were changing rapidly. Money, some of it dirty, some of it just overflow from the first bout of Wall Street “overexuberance” that would lead to regular crashes from the late Eighties to the Big One in 2008 began to filter into the neighborhood. Suddenly some artists were getting rich. Pursuing a lonely vision in honorable poverty was for chumps. “Fame, I Want to Live Forever” was the motto of the newer kids coming to the city to make art.

One of the overnight rich artists, Julian Schnabel, opened a restaurant on Tompkins Square that I couldn’t afford to eat in. That was another sign my string had run out in New York.

One day the sheriff of Seventh Street was not there and the next day a sign in Spanish telling folks he had passed away was placed on the bridge chair along with a small bunch of flowers. Other floral tributes were soon added. No one took his place.

My New York was disappearing by the hour and its news media, where I was trying to restart my career, was disappearing as well.

The New York Times was the first great cultural institution in America to be captured by what was not yet called neo-Conservatism. Twenty years earlier the Times had been the first major news outlet to embrace the Civil Rights struggle and portray it as anything but radical. Its editor, Turner Catledge, and the paper’s main reporters on the movement, Claude Sitton and Tom Wicker, were White southerners who had grown up in the Jim Crow South and knew its evils in their blood and understood the forces driving people to risk their lives to end segregation. Their reporting was both objective and empathetic to the struggle.

The paper’s correspondents in Saigon, David Halberstam and later Neil Sheehan, had been among the first to report with clear eyes the catastrophic failure of American policy in Vietnam. The institutional heft of the Times was at their disposal and in 1971 its proprietor, Arthur “Punch” Sulzberger, put the entire business on the line by authorizing publication of the Pentagon Papers.

These were heroic days. The managing editor who prepared the Pentagon Papers for publication was A. M Rosenthal. His connection to the story led to his elevation to Executive Editor. It was Rosenthal who changed the paper from being an institutional pillar of American liberalism to being a voice of neo-Conservatism. The op-ed page, allegedly separate from the news pages with its editorial staff housed on a different floor in the building to avoid contaminating the objective reporters, had long since become neo-con, advocating the “planned shrinkage” of the city’s population (see chapter Eleven).

An early definition of the term, neo-Conservative was “a liberal who has been mugged by reality.” The Times seemed permanently mugged by what Rosenthal and his top editors saw as the city’s physical and moral disintegration on the back of liberal programs. There was resentment about the ingratitude on the part of beneficiaries of these liberal programmes.

Rosenthal, like many other original neo-Conservatives had attended City College of New York, a public university that in the pre-World War 2 years had been the elevator to the middle class for the children of the millions of immigrants who had arrived in the city in the first two decades of the Twentieth Century, particularly Jewish immigrants. Admission requirements were rigorous but at a time when the Ivy League and other elite universities had strict quotas on how many Jews could attend, City College did not discriminate. It was also affordable: tuition was free.

Many students in the Depression and during the war had been instinctively on the left, Rosenthal among them. But City College was not insulated from the historical changes the Times had reported on in the 1960s. By 1969 CCNY’s student body was becoming less Jewish and more Black and Hispanic. In ugly demonstrations students demanded a more aggressive attempt by the adminisration to increase minority enrollment. The following year, strict academic requirements were dropped and a policy of open admissions was instituted. Enrollment increased but critics said it was at the expense of academic excellence because many new students were not prepared for college-level study. And as New York’s financial problems deepened the increase in number of students was not met with greater financial resources. In 1976, City College began to charge tuition.

For someone like Rosenthal, who began stringing for the Times while still a student, the perceived decline of CCNY was an example of liberalism run amok. Open admissions had caused a dramatic lowering of academic standards and also achievement. It was a paradigm of how the New Deal and its social democratic programs had become outmoded and unaffordable. In the view of these new conservatives this was a sign that a culture of dependency had been bred among recipients of these programs’ benefits.

Unspoken was the fact that most of the beneficiaries were Black and Hispanic. Also not discussed: the terrible fracture between the African-American and Jewish communities in the city that had begun in the 1960s, particularly over education. Many of the city’s veteran teachers were Jewish and as minority parents demanded greater say over curriculum and the color of those who taught it, conflict was inevitable.

In 1968, a confrontation between the local school board in the predominantly Black Ocean Hill - Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn and the teachers union, the United Federation of Teachers, led to a city-wide strike.

The Ocean Hill-Brownsville school board had only been established in 1967. Like other parts of the city, the neighborhood had undergone a rapid demographic shift in the 60s, from predominantly white and Jewish to overwhelmingly African-American. The new school board, elected locally, wanted more Black teachers and administrators for the neighborhood’s schools. They terminated the contracts of a number of teachers and school principals. Nearly all were Jews.

The confrontation between the board and the union took place in the weeks after Martin Luther King’s assassination when the entire nation was on edge. Words were said from which there could be no recovery of good will. Considering every other crisis in America in 1968 the strike was a small event but it had a terrible long term impact. It led to the collapse of the alliance among liberals, Blacks and Jews, that had propelled the Civil Rights movement in the South and made the City workable. That alliance has never been wholly reconstructed. The wounds from that confrontation festered for decades and they were still oozing in my last days in New York.

Journalism is a calling but it is also a business. We hacks like to think we report without fear or favour and with due objectivity about the world as we find it, but really the stories we cover and the framing of our reports are not/can not be entirely “objective”. When making decisions about what news to cover and how it is reported journalists and the institutions we work for do keep in mind the worldview of our readers, viewers and listeners for business reasons if nothing else.

Rosenthal had a good instinct for how the Times readers saw the chaos in the city and who was to blame for the situation. The lingering resentment over the Ocean Hill-Brownsville confrontation, the burning of neighborhoods that Rosenthal and other now successful people had grown up in and moved out of, was blamed on the people currently living in them.

His staff by and large shared his view.

Upon moving back from Washington to New York in 1983 I had sent clippings of the arts pieces I had written while a copy aide at the Washington Post to the editors of the Sunday Arts and Leisure section. I was invited to meet up for coffee. Arts and Leisure was the only part of the paper that took freelance contributions from cultural reporters.

Somehow the conversation worked its way around to the sleaziness of the Times Square area and how the editors felt unsafe walking past junkies and panhandlers on their way to the subway after work. I may have suggested to the pair they didn’t have it so bad and they should come down to Alphabet City if they want to see real urban squalor and how people cope with it. I might have told them about driving a cab on the night shift during the mid-70s and what I had seen while the city burned down and my analysis of what was causing the disintegration and what cultural riches were to be found in the Bronx, Brooklyn and Lower East Side. Or I may have said nothing and just sat slack-jawed as it became clear how different my idea of what to report about the city’s culture was from the two arbiters of what was fit to print about that culture wanted to tell their readers. In any case, the conversation did not go well. The editors never commissioned a piece from me.

Another harbinger of change had been Rupert Murdoch’s purchase of the New York Post in 1976. From front to back, the Post, which claimed it was the direct descendant of a daily journal started by Alexander Hamilton, was the paradigm of what a liberal tabloid should be. Its columnists did independent reporting to prove their points, they did not just spout ideological rhetoric. It’s sports pages had spawned a procession of Irish working class writers who invented a whole school called, “New Journalism,” in which the neutral, objective language of reporting was replaced by an almost novelistic author’s voice. Sportswriting became a place where the hacks could reflect on society. These meditations were made readable by the sheer storytelling energy of its Irish-American practitioners like Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill. A game was never just a game, a boxing match was never just a boxing match. They were struggles on the frontline of history with heroes and villains. Both men quickly left the Post after Murdoch took over.

Murdoch brought in veterans of his tabloids in Australia and Britain, particularly London’s notorious Sun, and gave the Post’s traditional readers whiplash as he almost overnight dragged the publication to sensationalism in news coverage and hard-right opinion in its editorials.

Murdoch’s Post played a huge role in amplifying the celebrity culture. The year he bought the paper Studio 54 opened. New York tabloids had always had gossip columns built around the goings on in society hang outs like the Stork Club but Studio 54 and its best known regular, Andy Warhol, became the key building blocks of a vastly expanded area of soft news: celebrities. More than the Post or any other newspaper, local TV news had been the key to celebrity coverage as a major news beat.

But it was impossible to reconcile reporting on the reality of the city in the 1970s with the business imperative of grabbing viewers who preferred to watch the lifestyle and celebrity stuff on the ever expanding local news shows.

On July 13, 1977, at around 9:30 pm New York’s power supply failed and the city went into blackout. Within minutes looting, arson and other forms of vandalism erupted in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

Judy Licht, a reporter for Channel 5, was dispatched to the site of one riot, Bushwick in Brooklyn. The blackout lasted 25 hours. Licht’s report from Brooklyn ran in the first news show after power returned. She could not keep the shock out of her face in her piece to camera about the Bushwick riot summarizing the violence and looting she had seen. This hard news piece was followed immediately by a previously taped Licht report on the new Elizabeth Arden salon opening on Fifth Avenue. Watching the two items side by side created a disturbing cognitive dissonance. My memory is the reporter was in the studio for a bit of happy talk either side of the Elizabeth Arden segment. Licht seemed to have recovered from the trauma of frontline riot reporting. She was much happier being filmed getting a facial at an expensive salon. And clearly the viewers were happier watching her enjoying one.

After 1977, with the Blackout riots and Son of Sam, and the continued burning of large portions of the Bronx and Brooklyn and Loisaida, the local news veered away from coverage of the causes of the city’s disintegration. Viewers didn’t want to be depressed when they turned on the news

The values of celebrity: money>prettiness>vapidity started dominating television and print journalism. It was in this time of changing journalistic priorities that a wannabe real estate mogul from outer Queens, Donald Trump, rode to fame.

This change had a huge impact on me personally. I hoped to do for cultural coverage what Breslin and Hamill had done with sports reporting, use it as a wedge to help people understand the society in which they lived. I couldn’t see where what I wanted to do fit in to this landscape of the ephemeral.

Downtown art started being reported on but for reasons that fit this era: because it sold for increasingly large sums. The artists who created it, like Julian Schnabel became celebrities, as much for the money they were making and their ability to hustle the publicity machine as for the quality of their work.

With money and celebrity involved, the news media began to pay attention to my neighborhood. The area of the city where the artists lived—my neighborhood—became a lifestyle destination. The New York Times, which had ignored Alphabet City and the far east of the East Village as it decayed into poverty and arson suddenly began reviewing restaurants and noting rising property prices.

WNBC ran a longish item on gentrification in Alphabet City. At the center of it was an interview with a Ukrainian tailor who had a little shop on Seventh between First and A. He had hemmed some skirts and trousers for my wife. We knew his story. He had lost his family to the Nazis, then after the war been deported East by the Soviets, escaped, made his way to America in the early 50’s and set up his little shop. He had stayed in the East Village when it had been abandoned to its fate.

Now he was crying into the camera, holding a piece of paper. A letter informing him his lease was at an end and his rent was going up by thousands of dollars a month. The tailor couldn’t possibly pay it. He had nothing to live for but his work and now it was being taken from him.

The man had survived Hitler, Stalin, junkies and firebugs but could not survive the force of gentrification.

The camera lingered on him to close the piece. When it switched back to the studio, Chuck Scarborough and his co-anchor, Pat Harper, ad libbed a bit along the lines of “whenever there is progress some people get hurt.” Yes. This is who gets hurt: the people who did not abandon the neighborhood when it went downhill, and who fought to keep families and community together.

That brief report and the “happy talk” ad lib afterwards made it clear to me that my “liberal” New York was finished. I was right to go. I didn’t think the Big Apple would miss me. The city of my birth is a real place but it is also an idea. Others —immigrants hoping to build a better life and colonists from the suburbs hoping to buy into the lifestyle we had invented—would come and re-make the city into their ideal image of it.

I could have moved to Brooklyn, I suppose. The next generation to come to New York would do just that and then repeat the process of gentrification, but for me Brooklyn was not the real city. That city was over.

Those final nights in New York, I watched “Is God Punishing Us?” with increasing disbelief. My memory tells me Rev. Jerry Falwell was one of the “experts” Chuck Scarborough interviewed.

Jimmy Swaggart may have been another noted theologian involved. His show was popular in New York not because the city’s people are religious—most aren’t—but because he was to televangelism what Mick Jagger was to rock and roll, the supreme entertainer, and Swaggart had yet to be found consorting with a hooker in New Orleans.

Nearly forty grey Novembers in London later, I have no regrets about leaving home.

And if you are wondering about the answer to the question, “Is God Punishing Us?” it was, “maybe”.

And the series won an Emmy.

This is the third chapter of Part Three of History of a Calamity, the story of how America went from Victory in World War 2 to Donald Trump and Cold Civil War in a single lifetime … Mine.

It is free to read but to keep going I need your help in two ways: please share it widely and also click on the donate button and make a contribution.

If you need to catch up on previous parts of my book, Part One, Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here:

AIDS stat source: https://www.factlv.org/timeline.htm

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/38976951/wnbc-news-4-ny-6pm-is-god-punishing/

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/05/local-news-media-trust-americans/618895/

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED203359.pdf

https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/10/nyregion/10legends.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_City_teachers%27_strike_of_1968

Sometimes history can turn on a tiny change in the rules. On August 4 1987, America’s Federal Communications Commission, the FCC, met in Washington DC to consider changing a broadcast regulation.

Another fine piece. I had forgotten how long Murdock's influence has been felt in the US.