Ambivalence is a hard thing to deal with in history. People crave simple narratives, chains of causation that are obvious. August 1914, September 1939, December 1941: war is declared, all life changes. There is a before and after. Simple as that.

But an aggregation of events that topples the old order without a clear indication that a new historical era has begun, that is more difficult for ordinary human beings to handle.

America’s Children of Victory grew up in a time of progressive politics. We have lived our adult lives in a reactionary age. When was the revolution? When was the war?

In the absence of a singular date, I propose the events of October 1973.

An anecdote from nearly a decade later:

It's a late summer evening in 1982 and the night train from Paris to Rome is about to pull out of the Gare de Lyon. I have just met a colleague on the train, a friend of my then girlfriend. We have never met before, have no idea what she looks like, but fate is at work and we have found each other almost instantly in the corridor of the carriage we have by chance thrown our bags in. As my girlfriend promised, we get on with each other instantly. As the train rumbles out of the station conversation flows.

The friend's name was Vicky, an Englishwoman, who worked at the International Herald Tribune. We were born in the same year and quickly found our way to the subject of the way our lives had turned out, and our surprise that we were regularly employed and living in a world where Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher ran our countries. This is something we would have thought inconceivable when we graduated from college a decade earlier. We had grown up in a time of limitless progressive ideas, now we were enmeshed in an age of reaction.

The paradigm had shifted but when? How?

Vicki must have posed the question. My answer was instantaneous.

“October, 1973.”

She nodded and continued the thought,

"That's right. October, 1973, is to our generation, what August 1914 was to the Edwardians."

I hadn't thought of that comparison but she was right.

October 1973 is to our generation what August 1914 was to the Edwardians.

It was the month when the world changed. Although like members of the British Expeditionary Force heading for France in autumn 1914 who thought they'd be home by Christmas, we didn't realize just how severe the shock was at the time. It was not stop the world in its tracks severe like the wars that shaped our parents and grandparents’ lives. The effects of this single month’s events would take years to become clear.

In that October, the Yom Kippur Arab-Israel war led to Arab states using their massive oil holdings as an economic weapon. They put in place an embargo on oil sales which led to prices quadrupling. This led to a terrible inflation which destroyed the remnants of the post-war economy. In both America and Britain that inflation would not be brought under control until the near simultaneous elections of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

That same month would also see the resignation of Vice-President Spiro Agnew as well as President Richard M. Nixon’s Saturday Night Massacre, the turning point of the Watergate scandal. The President would shortly follow his Vice-President and resign in disgrace. Young Republican Party activists like Newt Gingrich would begin to reshape the GOP into an instrument of vengeance.

Anecdotes are useful for understanding history at a personal level. For historians chains of facts are of more importance in building a historical theory.

It wasn't until the Crash of 2008 I discovered data to support my theory that October 1973 was the turning point.

Following the Crash, as the recession deepened across Anglo-America, economists and pundits noticed there was tremendous wealth inequality in America. Study after study was published demonstrating wage stagnation for most Americans began in 1973.

Fact: between 1946 and 1973, household income surged 74 percent. Since 1973, it has gone up by only 10 percent.

And it’s not just income. Almost all economic studies of the post war era, no matter what facet of the economy you are studying, use 1973 as the dividing line.

Fact: American steel production peaked in 1973.

Fact: Beginning in 1973, private sector union membership began to decline. 34% of the work force belonged to a union in that year. In 2020 it was 6.3%

Here is a snapshot of America just before the events of October 1973:

On September 15th, 1973, 117,000 workers at the automobile manufacturer Chrysler went on strike. The issue wasn't pay, which was pretty good already. The issue was overtime and retirement.

Despite economic noises off—removing the dollar from the gold standard—Americans were buying cars in record numbers. Chrysler plants were operating seven days a week, three shifts a day, to meet demand. The company’s contract with the United Auto Workers was due to expire and negotiations had hit a road block.

The workers wanted to be able to refuse overtime. To meet current demand, most Chrysler employees were on a six day week, nine hours a day, but younger workers—with no seniority to hide behind—found themselves doing 12 hour days seven days a week. Many of the newest people on the assembly line were veterans recently returned from Vietnam. After a couple of years in the army they wanted to get back to normal life. They wanted to date and get married and start a family. But working seven days a week, often doing double shifts, made that impossible.

Workers also wanted to retire after 30 years on the job with full pension and health benefits.

The company's concern was that if someone started on the assembly line straight out of high school at the age of 18 that meant retirement at 48. The actuarial tables said a 38 year old who already had twenty years on the line would live to the age of 61. A 23 year old recently returned Vietnam vet who started working the line in 1973 and who retired at 53 had a life expectancy of 65.

Paying full pensions for a dozen years or more was something the company management did not want to do. Management didn't want full benefits to kick in until workers reached the age of 56.

The company played hardball. The workers went on strike for the first time in 23 years. After nine days, Chrysler's management caved in. The executives even agreed to set up some pilot programs to study ways to relieve the tedium of repetitive assembly line tasks.

How many assumptions about the world are included in those numbers and how different they are from the world of today?

In September 1973, a person expected to work for a single employer for 30 years. An American automobile manufacturer would be selling so many cars, it needed to run three shifts a day, seven days a week. An assembly line worker's pay, relative to the cost of living, was good enough that he or she wouldn't need to work extra hours to make ends meet.

Unions were strong enough to win disputes because everyone belonged to them. The union for just one auto manufacturer, Chrysler, had 117,000 members. In 1973, the total membership of the UAW was close to one and a half million, today it is a little over 300,000. Although more than double that number are still collecting pensions. The assumption about life expectancy numbers was wrong in 1973.

The month before the world changed there were hints that the ground was already shifting, if you were paying attention.

On September 11, 1973, in Chile the military, with a little help from the CIA, staged a coup against the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende.

There was hardly any reaction on campuses or in Washingon.

From the moment President Nixon commandeered prime time on all three American networks in the spring of 1970 to announce that US troops were now fighting in Cambodia until the moment when 4 students were killed at Kent State University protesting the Cambodian invasion was less than a week.

But when Allende was overthrown there was very little protest.

This was an indication of how things were changing. In that era of upheaval and hope, the death of Allende and the imposition of martial law in Chile, should have sparked huge protests. Certainly, in the US it did not.

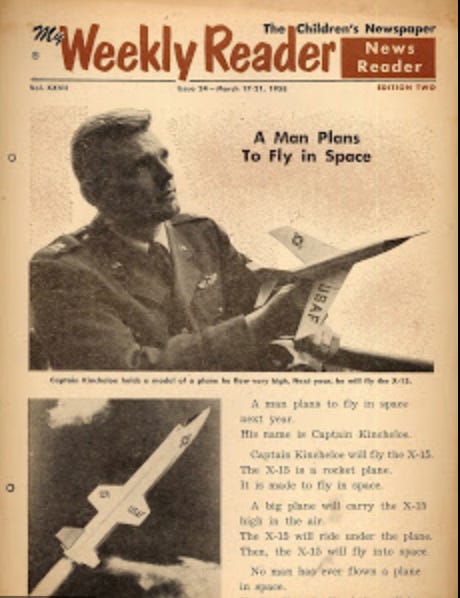

Thinking about the event now it is still a surprise because Chile was a country the Children of Victory, at least the ones who had taken to the streets against the Vietnam War, knew well. We knew it because of My Weekly Reader.

Who knows how stuff gets into peoples' heads? Why some of it shapes attitudes when other stuff just gets flushed out of memory? For Americans of a certain age, My Weekly Reader was the first place we learned about the world.

It was a news weekly aimed squarely at school children. In 1960, it had a circulation of over 4.2 million. My Weekly Reader told us about news in foreign lands and the things the American government was doing to help.

Latin America featured heavily. It was the time of the Alliance for Progress, President Kennedy's signature policy in the region. With US help, the continent would in Kennedy's words, "complete the revolution of the Americas." Living standards would rise, the curse of military coups and dictatorships would be banished by democracy. American-style democracy would increase prosperity and literacy.

Chile featured occasionally in My Weekly Reader. The country was held up as a beacon of democracy in a continent beset by dictatorship. Our 11 year old brains understood implicitly that Chileans were just like us. Chile was democratic and free. Its President, of Swiss-German ancestry, was even named Frei, which looked and sounded like free, and in German actually means “free.”

I was well into my university years and past being informed by My Weekly Reader when the ultimate proof of Chile's democracy was demonstrated: Salvador Allende, a socialist, an actual Marxist, was freely elected president.

Then on September 11th 1973 that democracy was snuffed out in a military coup, led by General Augusto Pinochet, with behind the scenes help from the Nixon administration. Allende, barricaded in his office in La Moneda, the presidential palace, shot himself.

The round-ups, torture, and summary executions began immediately. Americans and Britons were among the victims.

And nothing happened.

Nothing.

“The Whole World Is Watching,” was a chant of the late '60's. The eyes of the world on a dictatorship can’t prevent political evil but can ameliorate its effects. Yet in the weeks that followed nothing was done to focus the world’s attention on the Pinochet dictatorship.

Maybe it was because the news only drifted north in fits and starts. There was very little visual imagery and the newspaper reports were vague. “Some” people reported killed. “A thousand” reported killed. 90 reported killed. “No” deaths reported.

Maybe there was no reaction because Latin America exists as an afterthought for most people in the North.

Maybe the reaction was weak because the Kent State shootings had affected the collective sub-conscious. The minority who still protested America’s war in Southeast Asia—whose focus now was Cambodia—were genuine political radicals. The broader coalition against the conflict did not want to get too involved with radical politics and, possibly, were not willing to get shot while peacefully protesting.

Or maybe there were just a lot of people in the same in between place I was. Confronted for the first time with the necessity of making a living and, in a wider sense, just growing up.

That is the where the personal and the historical intersect. Historians look at economic and political and military events as affecting history’s flow but they rarely look at unavoidable things like people growing up and maturing. The collective putting away of childish things by people of a certain age is also a potent force of history.

Chile was free and democratic, just like the US, and its voters had chosen a socialist freely and democratically. As the years went by it became clear that Allende's overthrow had been aided and abetted by the Nixon administration.

Pinochet’s dictatorship, maintained by brutal abuse of human rights, was supported by American presidents for decades, in the name of America’s civic religion: anti-Socialism.

Still, the fact that there were no mass rallies remains a puzzle. Although by then the “left” in the US, which provided so much of the organizational energy for the anti-war movement, was doing what leftists have done for almost two centuries when the tide goes out: fight amongst themselves.

When I told my new friend on the train from Paris to Rome that October 1973 was when our world changed, included in that thought was the absence of reaction to Allende's overthrow in the weeks before.

The coup could not have been undone, but perhaps more pressure could have been brought on the US government to stop the massive abuse of people—people, as I had read in My Weekly Reader, who were just like us, in a democracy just like ours.

The failure to respond to Chile would embolden American presidents for decades to act with impunity in Latin America. Tens of thousands of people would be disappeared, tortured and murdered throughout the region with the tacit connivance and outright support of the United States.

At the time of that train journey I was just a beginner in journalism. When I became more established I tried to make amends for my own inattention to Chile and remind people about what had happened.

The last major news story I covered for NPR was the arrest of Augusto Pinochet in London in October 1998. Pinochet, a close friend of Margaret Thatcher, was in London for back surgery. A Spanish judge, Baltazar Garzón, had issued an international arrest warrant for the now-retired dictator on 94 counts of torture and murder of Spanish citizens during his time in power. The British government was obligated to detain the former dictator.

The demonstrations that should have happened in 1973 took place outside Parliament as the House of Lords debated what to do with Pinochet. Ultimately, after representations on Pinochet’s behalf from Thatcher and former president George HW Bush, he was allowed to return to Chile.

Among the people in the crowd I spoke to during the demonstration was a man named Luis Muñoz, a Chilean trade union activist arrested and tortured in the early days after the coup. A few years later I made an hour-long radio documentary on London's Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture. The first person treated there after the facility opened in the mid 1980s was the same Luis Muñoz. In the days following the coup, his pregnant wife was murdered and he was brutally tortured for months by the Pinochet regime. Munoz told me,

You cannot believe the sounds you make, you cannot believe a human being can make these sounds.

Although I was three decades late, it was still important to get his story to the world.

Chile—a place I have never visited— remains a signpost in my life.

One of my teachers, the Scottish poet Alastair Reid, had been an early translator of the Chilean Nobel Laureate, the poet Pablo Neruda. Literature breeds solidarity among people across borders and cultures in the secret spaces of the mind. That's why dictators like to kill the poets and ban their books.

Pablo Neruda died two weeks after the coup. It is still not clear whether he was murdered. It was one of the last major news events in the month before history entered the Age of Reaction.

You can find everything about life in Neruda’s work but one poem in particular, Nothing But Death, opens with lines that prophesy his country’s fate. And if an American reads the poem’s first four lines closely, he can hear a prophesy of his own nation’s march towards calamity.

There are cemeteries that are lonely,

graves full of bones that do not make a sound,

the heart moving through a tunnel,

in it darkness, darkness, darkness,

In America, the decades’ long slow fade to darkness would begin two weeks after Neruda’s death, in a war in the Middle East.

(Read on to Chapter Eight)

If you need to catch up on earlier chapters, Part 1 of the book , Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here.

Notes:

https://www.natlawreview.com/article/unions-numbers-2021-edition

nice writing, in particular this: "Literature breeds solidarity among people across borders and cultures in the secret spaces of the mind. That's why dictators like to kill the poets and ban their books." Thanks...

Melancholy and true. I remember that time and didn't know anything that was going on besides my small world. But the echoes reverberate and here we are in calamity that demands transformation