One of the rituals of American life on its descent to calamity has been the call for a “National Conversation About Race.” Whenever the country’s never ending agony over the original sin of slavery boils over you hear demands for one. It has become such a common occurence that the “Conversation About Race” has become a commercial proposition. Publishers rush out books with instructions on how to have one. Foundations give millions to organize conferences on the best way to conduct them. HR departments summon groups of employees to have supervised discussions on the subject. But long before there was money to be made, there were conversations about race all over the US. There always have been.

The Children of Victory were initiated into the ritual at the height of the Civil Rights Movement.

Throughout our adolescence the conversation about race was conducted on the evening news as the Civil Rights movement gathered pace. It was conducted standing next to high school lockers when people talked about music created by African American artists. Aretha Franklin conducted a seminar on race with each new release.

The news footage and the music and some of the adults in our lives opened the door to more in depth conversations on the subject.

For those of us born in the numerical middle of the American Century, 1968 was the year we began to have the conversation outside the confines of our home.

Sometime very early that year, my senior year at Harriton High School, I spent the weekend in the Mantua section of West Philadelphia, doing “community work.” The weekend was part of a fledgling program organized by the Society of Friends, in coordination with African-American ministers. It had been arranged by Thomas Fisher, Harriton’s economics teacher. There were a limited number of places. I expressed interest and was delighted when it turned out that the only other person going was our class President, Lynn Leymaster. Pretty, athletic, smart, she was a girl so far out of my league I hadn’t exchanged a word with her in all the years we had been at school together. Now there was a chance we might have some private time.

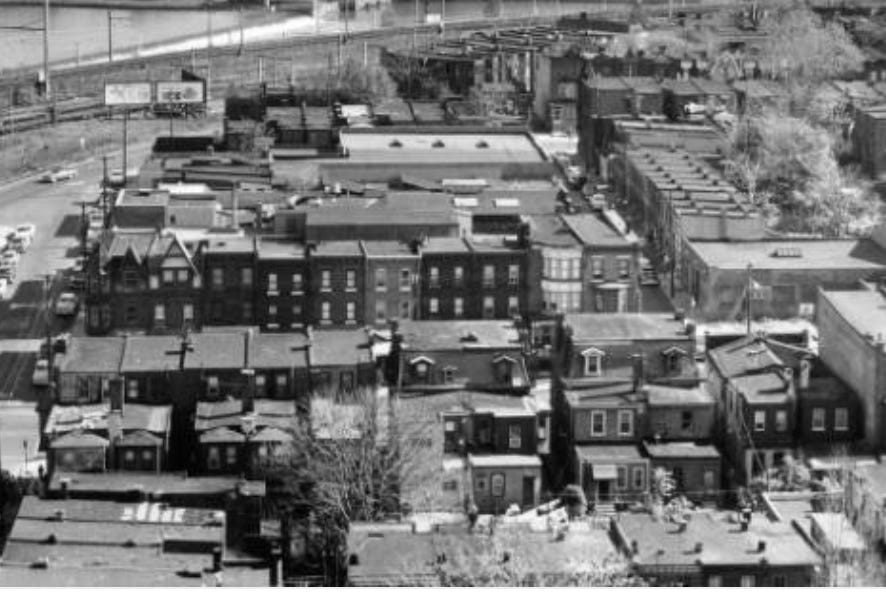

So on a frigid Friday evening we drove the seven or so miles from school to the Reverend’s house in the heart of the triangular grid of residential streets that made up Mantua. The neighborhood was not Philadelphia’s worst ghetto, that was North Philly, but it was certainly second or third.

Mantua’s history was similar to many such places in the old cities of America’s northeast and midwest. The district was developed as a leafy suburb with grand houses as Philadelphia expanded west in the mid-19th century. A generation later many of the large houses were knocked down, the lots divided up and row houses built. Working classes trying to get away from the close confines of the poorer districts moved in.

Throughout the 1920s the Great Migration of Blacks from the Jim Crow South brought a new mix to the neighborhood and after World War 2, White flight turned Mantua into a racially homogeneous place. Because the race in question was Black, not so benign neglect fell upon the neighborhood. There was lack of investment by banks, lack of services from the city, lack of a voice in decision making by either financial institutions or government. This was the typical foundation of all ghetto neighborhoods

The place was not unknown to me. To avoid the always jammed rush hour traffic on the Schuylkill Expressway, my father would drive home from the hospital through the area. When I had been downtown to see a movie or for a doctor’s appointment I would ride home with him The route was memorized. Turn right off Market St at 33rd and ghost along Mantua Avenue to Belmont Avenue, right at Belmont and then take it through Fairmount Park and into the suburbs. He could shave half an hour off his commute that way.

The streetscape viewed through the car window was of dull buildings, two and three stories high, packed in tight on one side. On the other were the railroad tracks heading west towards Harrisburg from 30th Street Station, the city’s main terminal.

The house where we were to spend the weekend was from the early phase of the neighborhood’s development, a big Victorian place that served as a vicarage and community center for the Reverend, his family and his flock.

The reason I keep referring to the man in whose home I was staying as the “Reverend” is not to preserve his anonymity, nothing in this story requires such a precaution. The reason is embarrassing. If you have read this far then you know I am cursed with an overactive memory but I cannot for the life of me remember the Reverend’s name. I can summon up his image: mid thirties, medium height. Everything about him was round and soft: his face, his mid-section, his voice. I have spent hours on google, the Library of Alexandria of our times, typing in search terms like Mantua 1968, community leader, minister but can find nothing about him. His name is completely lost to me.

But not his essence.

There was a communal supper where we introduced ourselves and the Rev outlined our tasks for the weekend. It was a small group. Not all were high school students. There were one or two middle-aged White folks. There was also a street kid—white—the Rev had taken in. The boy was deeply troubled, on the cusp of severe mental illness. In America, it is not uncommon for a white person who doesn’t fit in, whether a runaway or a rebel or non-conformist to gravitate toward African American communities. The person is trying to join their personal suffering to the group that is the embodiment of suffering in the society. The kid was the first example of this particular phenomenon I’d encountered.

There was a polite shyness in the dinner table conversation. The age range of people around the table would have made finding a single topic of conversation difficult. Was the conversation specifically about race? No, it wasn’t. Simply being in each other’s company, more specifically being a White person in a Black person’s home in an inner-city Black neighborhood, seated at the dinner table with his family, was communication enough on that subject.

The male sleeping quarters were a long climb up the stairs to the top and back of the house. It was cold with a draft coming through the window casement. A couple of pigeons were nested somewhere just above us and kept up a cooing conversation throughout the night.

Saturday we were broken up into teams and my group was sent to paint the apartment of an elderly woman who lived alone. We did not do the most professional job. There was no sugar-soaping the walls clean and putting on a base coat of primer. A bit of adult supervision wouldn’t have gone amiss. It was pretty much move furniture, open a can of paint and slap it on.

The street kid was in the work detail and chattered manically and was generally useless. He got under my skin and stayed there, a textbook example of the neurotic over-reacting to the psychotic. At one point, out of the blue he stabbed his paint brush into my chest, leaving a slash of white paint across my blue sweat shirt.

What the hell are you doing?

He laughed. “Relax. I was just joking man.”

He wasn’t.

Later, back at the Rev’s house I told him about what happened and he took time to explain the boy was troubled and had not had much love in his home life. Don’t let these things bother you, he said. The conversation branched off into his philosophy of bringing more love into the world, a precise extension of Martin Luther King’s beloved community of peace and justice.

After 24 hours on this project shyness had worn off and I may have questioned him on whether love would be enough to bring about the just world he spoke of. How did he deal with the racial hatred that was the fate of every black person born in America. “I don’t sweat the small stuff and I let God take care of the big stuff.”

We were up early Sunday morning, put on heavy workmen’s gloves, grabbed industrial refuse bags and went to a vacant lot to pick up months of accumulated rubbish. It should have been the city’s job but neglect was the fundamental relationship of most city governments to black inner city neighborhoods in 1968.

After a few hours of trying to drain that particularly filthy ocean dry, we went back to the Rev’s place, washed hands, changed clothes, packed up, and were bussed over to his church, a storefront near the intersection of Lancaster and Haverford Avenues. I realized I hadn’t exchanged a word with Lynn Leymaster the whole weekend and now that didn’t seem so important.

We sat among the congregation, a tolerated but alien presence, until the service began. For the first time in my life—but not the last—I experienced the syncopated musical grace of African-American worship.

Somewhere in his sermon the Rev reminded his flock not to sweat the small stuff and let God take care of the big stuff.

Then we were collected and dropped back in our all-white suburb.

That weekend was a conversation about race.

A month later I was back near the edge of Mantua at the Philadelphia Arena on Market St. Gypsy Joe Harris was fighting. It was a Monday night, a school night, but senior-itis had settled over all of us. College applications were in, attendance at school was an obligation but would have no bearing now on where we were accepted. My friend Doug and I decided to go check out the phenomenon that was Joe Harris.

Away from politics and the civil rights movement the main arena where the conversation about race took place was sports. Professional sport, much more than entertainment, was the one area of American life where racism ran up against the constraining force of fair competition. In open competition the best athletes won. Open competition for other forms of work, for political office, in every aspect of daily life was defined by racism. But not sport. And so sport, in parallel with the civil rights movement, became a main forum for the conversation about race.

The integration of Major League baseball had begun just as the Children of Victory were born and was the shining example of the possibilities of progress and integration. The former was defined by the latter.

Jackie Robinson was the first black player in the Major Leagues. He broke the “color” line in 1947. It was an event of such historical importance that three years later Hollywood made a full-fledged biopic about the event starring Robinson himself. Jackie Robinson was a university educated athlete and a young star of the Negro League, the professional league where black ballplayers were forced to play.

The film’s pivot point is a scene where Robinson and the Brooklyn Dodgers general manager, Branch Rickey, size each other up. Rickey has been looking for a way to integrate the Major Leagues. He is under no illusion about the kind of racist abuse the first black ballplayer will face. Does Robinson have the temperament to deal with it? He does. Rickey signs him. Robinson breaks the color line. He’s abused. He overcomes the abuse to become a star. Just as it happened in real life.

It was a story told to me from an early age and it was reinforced when a decade later the film became a staple on local television and I watched it in my suburban isolation. More than once. We grew up with integrated professional sport as something barely worthy of notice. It was virtually impossible to imagine the time before, an era just ended, when segregation was the rule in baseball.

Big-time college sport, particularly in the South, where there were no professional teams yet, remained segregated. Most of the major universities in the South were not integrated in any meaningful way. Only a handful of African American students attended places like the University of Misssisippi or Alabama, and the federal government had sent troops to force the state’s governors to admit those few.

The definitive conversation about integrating college sport took place on a basketball court, March 19th, 1966. Texas Western, a small college in El Paso beat the country’s most historically successful team, the University of Kentucky for the NCAA national title. Texas Western started five black players, Kentucky, of the Southeastern Conference, had none. Before the game, Kentucky coach Adolph Rupp summarized what was at stake, ''No five blacks are going to beat Kentucky.''

But they did. And the following year Kentucky began recruiting black players and eventually the entire Southeastern Conference integrated.

By the mid-60s, the intensity of the political struggle around civil rights and undoing Jim Crow was matched by rapid disintegration of African-Americans’ willingness to accept the separate but unequal social customs that, for want of a better phrase, showed they “knew their place.”

This dynamic played out most clearly in public view among athletes. Jim Brown, was the best player in pro football and is arguably still the greatest player of all time. He was a running back for the Cleveland Browns and had, in his nine seasons, set every record there was to set. Brown was also aware that at a certain point, football would end and he would still have more than half his life to live. He thought clearly about what he would do after his professional sports career was over. He would become an activist on behalf of black enterpreneurs and organized the Negro Industrial Economic Union. He also wanted to be an actor and in the off-season took filmwork.

In the summer of 1966, he was in Britain filming The Dirty Dozen. Shooting overran and so he missed the opening of training camp. The Browns’ owner Art Modell sent Brown a message via the Cleveland newspapers. The owner was fining him. No man is bigger than the team.

Brown wrote Modell from the film set.

"I am writing to inform you that in the next few days I will be announcing my retirement from Football. This decision is final and is made only because of the future that I desire for myself, my family, and if not to sound corny, my race.”

I feel you must realize that both of us are men and that my manhood is just as important to me as yours is to you.

Brown proved adept at sending a message through the press, as well. He gave Sports Illustrated’s lead football writer, Tex Maule, an exclusive interview.

I want to have a hand in the struggle that is taking place in our country, and I have the opportunity to do that now. I might not a year from now … I quit with regret but not sorrow.”

Jim Brown’s retirement while still at the peak of his ability became a strand of the national conversation about race.

“What do they want?” was a question Brown’s decision to quit raised.

The following year Muhammad Ali superheated the conversation sparked by black athletes when he refused induction into the Army at his draft appearance. Ali had defined himself against knowing his place when he joined the Nation of Islam shortly after defeating Sonny Liston for the heavyweight championship in 1964. He changed his name from Cassius Clay - his “slave name” - and insisted that sportswriters call him Muhammad Ali. It was as decisive an expression of “not knowing your place” as could be imagined. Ali’s name became a litmus test in the national conversation about race. As he worked his way through the heavyweight division fighting and defeating all comers, writers and fans views about him could be understood by whether they called him Ali or Clay.

This was not a small conversation. The New York Times report on April 29, 1967 of the boxer’s refusal to take the oath at his draft induction reads:

Cassius Clay refused today, as expected, to take the one step forward that would have constituted induction into the armed forces. There was no immediate Government action.

Although Government authorities here foresaw several months of preliminary moves before Clay would be arrested and charged with a felony, boxing organizations instantly stripped the 25-year- old fighter of his world heavyweight championship.

A few weeks later Brown’s Negro Industrial Economic Union organized a meeting with Ali and leading Black athletes including basketball stars Bill Russell and Lew Alcindor (who would later convert to Islam and change his name to Kareem Abdul Jabbar).

The assembled sportsmen’s hope was to convince Ali to accept induction. Ali was told by the group’s lawyers that a deal with the government had been worked out. He would not have to see combat in Vietnam. He could spend his Army service doing boxing exhibitions. The other athletes were concerned that his individualistic stance would make it more difficult for them to use their athletic accomplishment to bring economic opportunity into black communities. Ali was not swayed and the meeting broke up. Bill Russell remarked.1

He has something I have never been able to attain and something very few people I know possess, he has an absolute and sincere faith … I’m not worried about Muhammad Ali. He is better equipped than anyone I know to withstand the trials in store for him. What I’m worried about is the rest of us.”

Gypsy Joe Harris was not political, but he was a rebel in his training and fighting technique. He was a welterweight from the North Philly streets and trained with all the indiscipline associated with street life. His fighting style owed more to James Brown’s dance moves than the traditional up on your toes, plant, stick and move that classically trained boxers learn. He didn’t hold his fists up to protect his head but kept them tight across his chest, He moved in on opponents as if he had the rhythm section of Brown’s band, the Famous Flames, pumping away between his ears. He had an uncanny sense of incoming punches, sometimes spinning 360 degrees away from them, obliterating the rule to never turn your back on your opponent.

The reason for his style lay in a fact that he kept hidden. He was completely blind in his right eye and had been since he was 11-years old when another kid hit him in the head with a brick. On the North Philly streets he had had to develop a sixth sense for danger coming from his literal blind side.

The Gypsy at this point was undefeated and had become a national sensation complete with a cover spread in Sports Illustrated.

Doug and I paid a few bucks to sit up in the last row of the Arena’s balcony. Given the location of the venue, deep in the West Philly ghetto, and the night of the week, and the price of the tickets, we were the lone white faces in the balcony.

We stared down at the ring through a fug of menthol and cheap cigar smoke. What the Black men who surrounded us thought of these two white, obviously Jewish boys, in their midst I have no idea. There was no hassle and no harassment, the temporary equality of sports fans at an event.

We eavesdropped on the banter, watched as pints of whiskey in brown paper bags were passed around. Occasionally made eye contact and nodded heads after a particularly sweet round for the Gypsy. I probably bummed a Kool and fake smoked it.

Harris won handily. I don’t think we stayed for the final bout of the night, we had school the next morning. We nodded to the fellows we had been in company with and side-stepped down the row and over to the exit.

Sharing the cheap seats, the smoky atmosphere, the pleasure of watching a unique Black athlete; as at the communal supper that first night at the Reverend’s, simply being in company in a Black person’s house:

That was a conversation about race.

April 4, 1968. Martin Luther King was assassinated. Speechless.

June 5, 1968 Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated. Speechless.

There were no conversations you could have.

Before there was NPR, there were simply individual public radio stations, and in Philadelphia that station was WUHY. Today the call letters are WHYY. Before NPR pioneered the concept of delivering news with a vocal hug to its listeners, “educational” radio was free-form, experimental with sound and hard-edged, almost radical, in reporting the news.

For most of the summer of 1968 I worked at WUHY as a copy boy, monitoring the newswire room, tearing off stories as they printed out on the teletype machine and delivering them to the appropriate reporter in the understaffed newsroom.

After a few weeks I was invited to think of a story I might do for the drive time news program. The WUHY studios were in West Philly, a short walk from the Rev’s house in Mantua. It had been a a few months since Dr. King’s assassination. I wondered how the catastrophe had effected him and his neighborhood, pitched the idea of an interview and the editor sent me off to do it.

I walked over to the big house on a sweltering day. The Reverend welcomed me back, asked me if I would like some sweet iced tea, “Yes, please,” and while he went off to get it, I took out a new kind of tape recorder, a cassette machine, fiddled with it, and plugged in an external microphone I had very little idea of how to use. I also had no idea how to conduct an interview, for that matter I didn’t know interviews were “conducted.”

I pressed record, extended the mic in his direction and we just talked. Or mostly, the Reverend talked. He had things he wanted to say and not knowing what I was doing I just let him say them. He free associated his way through his grief about Dr. King’s murder and the terrifying doubt it had put in his mind about non-violence and love as a way to bring about a just society.

The patient approach of non-violent political pressure to achieve change had had some success. The various civil rights acts that had been enacted since Lyndon Johnson took office were proof. But removing legal segregation in the South and guaranteeing voting rights did not end de facto segregation in housing in the rest of the country. It did not make a dent in the de facto segregation of the job market. Although it was a golden age of jobs for everyone, Black unemployment remained two and three times higher than White unemployment. There was an anger that simmered about these conditions on the streets just outside the Reverend’s door and across America’s urban landscape.

In 1965, just days after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act, the Watts riot in Los Angeles exploded. 34 people were killed, an estimated $40 million in property was destroyed. Riots broke out every summer. Ineffectual, heavy handed policing, often backed up by deployment of Federal troops, only intensified the anger in the inner cities. A new generation of activists for racial justice rejected the idea of turning the other cheek. They were sweating the small stuff, the big stuff and all the stuff in between.

Stokely Carmichael, a dozen years younger than King, rejected non-violence as a strategy and integration as a goal. Carmichael’s call, echoing Malcom X, for “Black Power” was an effective rallying cry outside the Rev’s front door, more effective than singing repeated choruses of “We Shall Overcome.” In the last year of his life Dr. King was regarded as a man whose time had passed by many younger African Americans.

The Rev was a disciple of Dr. King. But four months after the man’s murder he was questioning how far non-violence could carry people—his people—to a truly equal place in American society. Just to ask the question of himself was a shock. A world view, a plan on how to live had been ruptured.

And to his monologue of grief and doubt there was nothing I could add, either by a question or a worldly comment or an empathetic remark. My life experience had not supplied me with either thoughts or words to say.

When he had finished speaking. I packed up the cassette machine, stood up and shook hands. He thanked me profusely, “I never expected anyone from the news would want to know what I had to say.”

I was just 17. He was more than twice my age, with a family and responsibilities I could not yet imagine. Without intending to he taught me the single most important lesson any journalist can learn. You are giving a voice to people who have none.

Back at WUHY, listening with an editor we decided the emotional power of the Reverend’s voice was so great that we would turn the interview into a virtual monologue, a piece of unmediated media. Like I said, public radio was free form, experimental and radical back then.

And that was a conversation about race.

(Read on to Chapter Five, part 2 here)

https://theundefeated.com/features/the-cleveland-summit-muhammad-ali/

As with all the articles from Michael Goldfarb, Chapter 5 combines pathos and data. I relive the times and feel there must be a way that we can move forward in this ongoing discussion

Thoughtful, reflective. Thanks