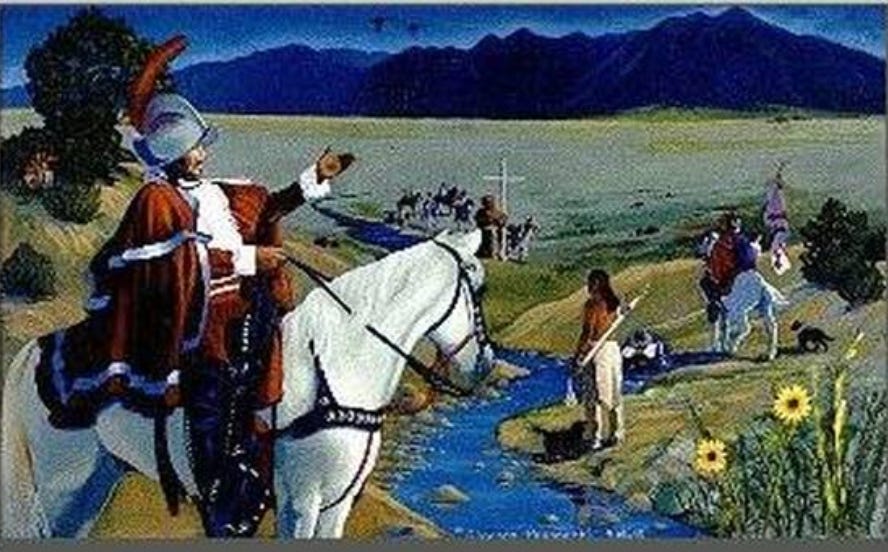

Towards the end of my journey along the border, in the town of Mesilla New Mexico, a teacher gave me a history lesson: Exactly 400 years ago in the spring of 1598, the Spanish explorer Don Juan de Oñate led a party of settlers from Mexico over a great river, the Rio Grande, and headed north to set up a colony.

600 people set forth with him to found “Nueva Mexico”—New Mexico. The settlers were accompanied by soldiers, to protect their bodies, and priests to pray for their souls. They called the place they forded the Rio Grande, “El Paso del Rio del Norte”. Today the place is called El Paso, Texas.

The expedition carried on to the north, hugging the foothills of the mountains along the river plain, burying their dead along the way. After travelling through mountain and desert for several hundred miles they set up a colony and called it Santa Fe. And all of this happened a quarter of a century before the Pilgrims founded Plymouth colony in what was not yet called Massachusetts.

The man teaching me this lesson was Paul Taylor, and despite the English sound of his name Paul Taylor could trace his ancestry back to those early Spanish settlers. We were seated in the living room of his house in Mesilla, surrounded by portraits of his ancestors going back to the 18th century. The Rio Grande flows not far to the West. The route taken by Don Juan de Oñate is not far to the east, and El Paso is just 40m to the south.

Paul Taylor told the tale of Don Juan de Oñate with an urgency. He wanted me to know the story and with his teacher’s eye, looked at me to make sure I was understanding it. When he finished the story of the conquistador, he began to recount the story of his life, or the transforming experience of his life. Taylor, with his fine white hair, straight nose and bespectacled blue eyes, looks like an energetic English pensioner, yet despite his English looks, as a schoolboy he had been brutally teased by his classmates because his mother’s family was Hispanic.

“I was called a coyote,” he remembered, slang for someone of mixed blood, a real insult back then, 70 years ago. The shock of other white boys ostracizing him because of his mother’s blood set Taylor on his energetic life’s course, teaching and helping his fellow Hispanics gain their full rights in the United States.

In retirement he took his energy into politics, and won a seat in New Mexico’s state legislature. Public health along the border had become his passion. As Mexican immigration, legal and illegal, had increased in recent decades, so had the public health problems of the area. The new arrivals set up their own towns called colonias.

The fact that the colonias often have no running water or other basic sanitation facilities, makes the risk of disease high. Paul was keen for me to visit one. My problem was that I needed to get on down the road to El Paso, Texas. El Paso was supposed to be the end point of my Border Run and I had to return to London in 2 days. Paul however is a persuasive man and before I could say anything he was on the phone to a local health official to organise a little tour of a colonia and then take me to El Paso to meet with other public health workers.

‘Will an official from New Mexico know what’s happening in Texas?’

"Borders don’t mean much around here.”

Paul took me to Las Cruces, New Mexico and at the public health offices—a new building where the white haired teacher/legislator was greeted warmly—he handed me over to Dan Reina, Director of Border Health. Reina in turn handed me a thick dossier of material. Throughout this trip I had been trying to understand the border region by meeting the people who live there. Now I was being given a different view; the view of statistics. The border I knew was an empty place; vast expanses of desert and mountain. The border described in the information handed to me by Dan Reina was teeming wth people, a region whose current population growth was three times greater than anywhere in the US.

Here are the numbers:

At the turn of the century, only 30,000 people lived along the US-Mexico border. Today, in 1998, that number is 11 million. The reason I hadn’t seen all these folks is that they live in 12 pairs of sister cities: 12 cities either side of a border that runs for 2,000 miles. The numbers carried on; 72% of the population is Hispanic. 38% live in statistically defined poverty. The incidence of disease is high.

Dan drove me down to the colonia in La Mesa, New Mexico. It was a poor place, although not the worst poverty I’ve seen in America. The colonia had been settled for too long. Houses had been built and in their yards were mundane signs of permanence, of a suburban neighbourhood taking root. Children’s bicycles, a basketball backboard nailed to the side of the house, barbecues. Still, the roads were unpaved and the electricity lines looked ramshackle. It was the middle of the work day and the unpaved streets were empty.

Eventually we came across a woman standing with her arms folded looking down at a man digging a hole. We stopped and Dan started talking to the woman. Now, most people in the colonia would not volunteer information about themselves to a stranger, too many still live in fear of the immigration authorities and being deported back to Mexico, but this woman was extremely confident. She and Dan began an animated chat in Spanish, Dan translated bits of it for me as the woman told her story.

One day after working in the fields she had gone to the supermarket to buy groceries. Her young son was with her. While standing in the checkout line she noticed that some of the white people in the line were whispering and laughing. This continued for a while, so she asked her son in Spanish what’s so funny.

“He said, “Mommy they are laughing at you.”

“Why?”

“They say you stink like onions.”

“So I told my son to tell them I smell this way because I’m picking the onions they eat.”

The boy did, and they stopped laughing. The woman smiled in satisfaction at the memory. A short while later, her son came by. He was 11 now; his mother introduced him. The boy, who spoke English perfectly well, was much less communicative. He was in fact sullen and distrustful. The son’s arrival ended the bilingual conversation.

We said goodbye and drove out towards Interstate 10, the local highway, and headed south to El Paso. I asked Reina about that interaction.

“The woman seemed more trusting than the boy.”

“The first generation born in the US always find it more difficult. They feel that they are not Mexican, but they are not accepted as American either.”

The boy’s sullen distrust was perfectly understandable to him. He had an acute understanding of the problems of Mexican immigrants because he is himself Mexican American. Born in Brownsville Texas, 1200 miles further down the Rio Grande.

The traffic on the highway began to jam up as we reached the outskirts of El Paso. El Paso and its Mexican sister-city, Juarez, form the centre of the border region. Up to this point, the border is an imaginary line in the desert sometimes marked by fences of differing efficacy. From El Paso heading east to the gulf of Mexico, it’s the Rio Grande. It was hard to identify the heart of the sprawling city. The main local landmark, the largest American flag in the world, which usually flies at one of the border crossings, was furled for some reason.

We drove to the office of Jorge Magaña, the city’s public health chief. Magaña was from the Yucatan in southern Mexico. He had come to El Paso 40 years before for his medical training, and had never left. We were joined by Hugo Vilcis, another public health specialist who is also Mexican by birth working in Las Cruces, New Mexico just north of Mesilla.

As the public health officials spoke, I was in the world of statistics again. Incidences of tuberculosis, cholera cases coming closer to the American border. So many people going back and forth, transiting through the border legally and illegally - it was a public health nightmare. The statistics poured out, but the most important one was this: every day 1.6m people legally cross the border each way between the United States and Mexico.

No international border experiences anything like that daily migration; people go from one country to the other to work, to shop. The border area is a region stretching many miles inside both countries. These public health professionals wanted its regional nature recognised by the Mexican and American governments. They were all agreed that the line on the map, or the course of the Rio Grande wasn’t the real border.

“I always tell people, the Rio Grande is not a natural border,” Reina said. “It’s easy to get across. The border really begins at Interstate 10. More illegal immigrants get killed trying to get across that highway than crossing the Rio Grande. ”

The next day I went down to the river and walked over the bridge to Mexico. You have to pay for the privilege, a small amount, too small to remember accurately, perhaps 20 cents. Juarez was bleak and hard and alive in the middle of the morning. The streets swarming with thousands heading towards the bridge to walk over to the US side.

Mexican federal police mingled in the crowd, detaining people, examining their papers. Looking down from the middle of the bridge, the river is not so grand. It flows shallow and tame through concrete embankments. It’s not the wild natural barrier Don Juan de Oñate and his party forded 400 years ago. You could probably wade through it most of the year now.

El Paso/Juarez reminded me of the limits of my work method. Millions were crowded either side of the river and like people in any large city they were hustling and bustling to get places and not interested in speaking to a stranger passing through, especially one who couldn’t do much more in Spanish than order a beer in a bar. On this Border Run I had stopped in much smaller, less hurried places and had no trouble finding people who wanted to tell me a story and hear some of mine.

But El Paso, like all new sunbelt cities, was an imitation of Los Angeles sprawl, with people rushing places in cars and very few pedestrians just hanging out. Juarez had a mad, sullen, violent energy and it would have taken more time than I had to find a key to open it up and begin to understand its intimate relationship to El Paso. I would have to return. Some day.

I walked back to my car thinking about the historical connection the not so grande river represents, rather than the separation it embodies. Rivers are living things and they frequently change course over time. So do borders. It wasn’t until 1964, here in El Paso, that the last bit of the US-Mexican border had been finalized. This is the story behind that obscure fact:

At the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the Treaty of Guadeloupe-Hidalgo stated that the middle of the deepest part of the Rio Grande’s channel was the border between the two countries. By the end of the 19th century floods had shifted that channel south significantly. A tract of land had been created as the river changed course. This area was called Chamizal, after the chamizo, a scrub plant that quickly took root there.

To complicate things, the changing river course had created a horseshoe bend and to control flooding, both governments dug a channel across the bend. What this did however was create an island on what was now American territory, except that under the terms of the 1848 treaty this newly exposed knob of land would have been in Mexico.

Starting in 1895 various Mexican governments demanded that the land be returned to Mexican jurisdiction. This was no small thing: Presidents were involved in negotiations and international bodies were summoned to arbitrate. It wasn’t until Lyndon Johnson, a Texan, was President that a final agreement was reached on the border, land was swapped and the wild river was banked in with concrete so that it’s course could not shift.

The dispute might seem trivial and most Americans don’t know about it. I certainly didn’t and finalizing the border was an event that happened during my lifetime. I drove the few miles from the pedestrian bridge to the Chamizal National Memorial. There was not much to see, the chamizo is not a very interesting bit of flora to look at and the river is very tame.

I sat in the car listening to the radio. Most of the stations were Spanish. I couldn’t quite follow the language but I could follow the station formats. They were identical to what you would find anywhere in the US except everything was in a different language. There was top 40 Spanish music, there was all-news Spanish radio. There was a call-in show in Spanish. I can sort of follow conversational Spanish even if I’m not quick enough to take part in a conversation. The topic of discussion seemed to be how to maintain one’s sense of Hispanic identity and still be part of the majority Anglo culture in the United States.

At that moment, in that place, all the arguing over the border line and the meaning of culture seemed absurd. The border is its own region with a culture created by immigrants who are not immigrants. The land, the history of the region is theirs. I think this is the real lesson Paul Taylor wanted me to learn when he told me how, 400 years ago, Don Juan de Oñate a Spanish explorer, headed north out of Mexico, crossing the Rio Grande at El Paso del Norte. One way and another, people from Mexico have been crossing north ever since. This movement of people is the fuel powering the engine of history in this part of North America. History, like the Rio Grande, can change course. Perhaps someday it will be necessary to re-draw the border line again, to take into account the special nature of the border and its people.

Call this new area on a map Chamizal.

It was time to go home. I headed west towards Phoenix, Arizona, and was back in the more familiar border landscape of epic emptiness, flat desert floors, razorback mountain ridges at the horizon. I got onto Interstate 10, and was making good time across New Mexico when I had to slow down for a roadblock. An emergency border patrol station had been set up along the highway. At that point, the actual international boundary was 40 miles to the South. Dan Reina was right, the border really does start at Interstate 10.

A uniformed border patrol cop, a Mexican-American, took a look at me and my car, and waved me through. 200 years ago, his ancestors would have said to a passing stranger, “Vaya con dios”—go with God. As I drove off, the border patrol man said in English, “Have a nice day.”

Border Run was the last of the reporting trips I made for the BBC World Service in the 1990s. Of the three regions I visited the one that has changed the most is the border.

In the Midwest, the fragmenting of the country and the melding of conservative politics with fundamentalist Christianity was well underway. 30 years later the biggest change may be the change in nomenclature: fundamentalists now call themselves evangelicals.

In Mississippi, the post-Civil Rights era South had moved had evolved to a place where “separate but equal” was not an ironically racist phrase in the notorious Supreme Court decision in Plessy v Ferguson handed down a hundred years earlier, but an accurate description of society. Blacks and whites “tiptoed” around one another which allowed the Confederate mindset to malinger and occasionally re-erupt into American history. That is still the case.

But there is no doubt that the border area has undergone signficant change. Feeding America’s drug habits has turned the Spanish-speaking Caribbean and Mexico into narco-land. Juarez became home to a major cartel and drug-trafficking violence came to define the region.

In addition, Central American countries, long-destabilized because they were proxy battlefields in the Cold War competition between the US and Soviet Union, became unlivable and are today the source of a stream of migrants desperate to get to the US. Where there is desperation there are always criminals to take advantage of the situation.

Twenty-five years later I realize how lucky I was on my border trip. It was a combination of shoe leather reporting and sheer luck that I met men like Charlie Page, Alex Amado and Paul Taylor. The men were very different but each had a profound love for the unique qualities of border life, especially the laissez-faire attitude to human beings, bred of a history in which the lines on the map and ethnic lines between people are not so important. All three were happy to share what they had learned in their long lives.

I was also lucky in the timing of the trip, because I doubt very much that laissez-faire attitude has survived the violence literally the other side of the river in Mexico and the relentless propagandizing and sensationalizing by 21st century American news media of border issues. The demagoguery surrounding immigration by nativist American politicians has made it almost impossible to see the Border clearly.

And it is nearly impossible to do this kind of reporting now. Journalism has been a serious casualty of the polarization processes that have split American society. People tend not to want to talk to strangers anyway, but when you introduce yourself as a reporter just passing through people tend to hurry away or worse.

Another reason this kind of reporting is difficult: many of the people I met on these three trips came into my range by chance but sometimes I pushed the process along by dropping into the local newspaper. No one knows a town and its surroundings better than reporters and editors who cover the area. But as many as 2500 local papers in the US have closed down in recent decades.

In 2018, I was in Texas to do some reporting on the mid-term elections and went back to the border. I arrived in Del Rio about 400 miles downriver from El Paso and did a quick recce. There was a rundown but potentially charming downtown which was full of buildings from the first half of the twentieth century, and west of it was a 21st century stretch of strip malls and fast food joints. The downtown was empty except for a few elderly Hispanic men, the strip was full of cars rolling from one parking lot to another. I couldn’t crack this centreless town open so I went to the office of the Del Rio News-Herald and asked to speak with the editor.

Ruben Cantu came out and vetted me, to make sure I didn’t have some kind of agenda because, as he explained, most reporters coming down to the border already know what they expect to see. Having satisfied him that I was not there to find headless corpses or bodies floating in the Rio Grande or look for narcos to interview—in other words didn’t arrive with a cliched preconception of the border—we had a pleasant chat and then he invited me to the monthly meeting of the Del Rio Wine Club. It was not the experience I expected to have on the border and it was eye-opening.

The Del Rio News-Herald went out of business two years later.

This chapter marks the end of Part IV of History of a Calamity: America 1990s, Adventures in Flyover Country

This Substack grew out of work I have done for the BBC ever since I ex-patriated myself from my native country in late 1985. A precise thirty years later, in late 2015, I convinced BBC Radio 4 to take a loud-mouthed television reality show host and serial bankrupt real estate mogul seriously as a presidential candidate and to let me make a documentary on him and the paranoid political tradition he represented. It aired the night before the first primary of 2016. The documentary made it clear to listeners that Donald Trump should be taken seriously and his prospects for reaching the White House were very good.

Trump’s victory the next year was a calamity and also the seed for this project. How did America get from the glow of victory into which Donald Trump and I were born to this terrible state of social fragmentation and cold civil war?

The assault on the US Capitol building of January 6, 2021 propelled me to begin the work. The book was outlined pretty quickly and a month later the first chapter appeared on Substack. I have adhered to that outline. Part V: The Calamity, the last section of the book was supposed to have been completed before the 2024 presidential election.

But the need to earn a living intervened. There were long breaks from working on it in order to dream up and propose documentary ideas to BBC radio, and further breaks to actually make the programs.

So now writing the final section of this memoir, a history from below of how America reached this parlous condition in a single lifetime, will coincide with the most consequential American election in that lifetime. Look for it in the months to come and in the meantime, please share the existing chapters widely.

And if you need to catch up, the book begins here:

If you haven’t already, subscribe to my other substack, First Rough Draft of History