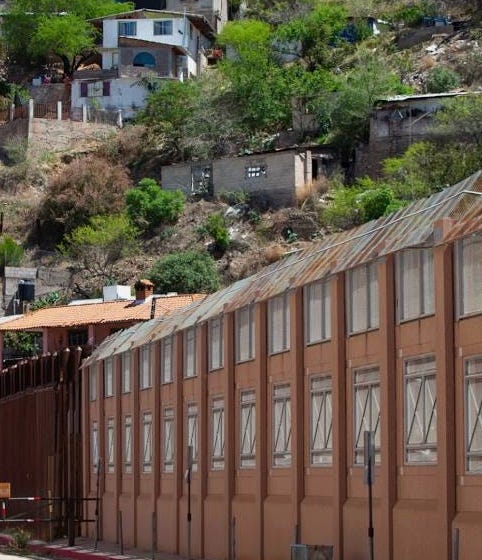

In Nogales, Arizona, the border is pink. A wall of cinderblock and metal painted pink running between two voluptuously rounded hills that define the town. In the flat canyon between the hills, there’s room in the wall for a pair of railroad tracks and a multi-lane road running into a city on the Mexican side of the wall. It too is called Nogales. Nogales, Sonora. Sonora is the northernmost state in Mexico.

It was Friday. A week before, in a much smaller border town near Yuma Arizona called San Luis, a couple of hundred miles to the west, a retired schoolteacher called Charlie Page had told me to visit Nogales if I really wanted to get to know the border people.

“They are the friendliest, most generous people in the world - they’ll take you in. They’ll share what they have with you. They’ll make you a carne asada.”

Carne asada is the local barbecue, and at this point hanging around a bunch of friendly people and eating a communal meal sounded pretty enticing. In the several hundred miles between San Luis and Nogales along the border there are no towns to speak of, just desert and mountain. Frankly, I was lonely and desperate to be surrounded by human beings.

After the barrenness of the desert with the only signs of human settlement crossroads hamlets with names like Why and Ajo (garlic) arriving in Nogales, Arizona, population a mere 20,000, was like entering a heaving metropolis. I happily got stuck in a traffic jam on the wrong side of the railroad tracks waiting for a freight train to slowly pull north out of Mexico. Then, since the traffic wasn’t going anywhere, I parked the car and took a walk.

The two Nogales have not been around all that long, just since the 1880s when a railroad depot was built here. That was a fact I found out when I wandered into the local historical society building where I was quickly engaged in conversation by a white-haired woman in her early 70s who wanted to know everything about me, in the friendliest way.

So, I explained I was travelling along the border to see what effect it had on people’s lives. The white-haired woman understood what I was trying to do:

“Well the border didn’t used to mean much; we crossed back and forth all the time. We intermarried. My daughter married a Mexican. Most women my age have Mexican grandchildren. But the Maquilas changed all that.”

“What are Maquilas?”

“Oh, factories over in Mexico. Have you been to the Mexican side?”

“No.”

“You should go.”

So I did. It was no hassle. People were walking and driving back and forth through a customs station without much ado. Flashing an i.d. was all it took.

On the other side of the wall, the border is not pink. It is the colour of dust. In its shadow, people had set up little encampments of boxes and plastic sheeting from which to launch their attempts at crossing illegally into the US.

The buildings in downtown Nogales, Sonora are cracking from neglect, or the weight of the gaudy signs bolted into their fronts. The place was packed with American day-trippers, hawkers selling tourist tat, local office-workers and those who had come to Nogales looking for work and had not found it.

I sat for a while in a concrete plaza looking to find a conversation, but my Spanish wasn’t up to the task and none of the idlers who came up to ask for money or a cigarette seemed to speak English any better.

Back through the border in Nogales, Arizona, I returned to the historical society and pretty soon was talking to Scott Bell, a guy in his early 30s who, like the white-haired woman, wanted to know—in a friendly way—what brought me to town. I explained the purpose of my trip again. Scott kindly offered to introduce me to some friends of his, people who had been living in Nogales, both sides of the line, all their lives.

He drove me to my car and then I followed him back to his place north of town, heading towards Tucson. We turned off the highway and went down a long gravel track through a landscape that looked doubly familiar. Over the previous week I had grown used to the border landscape of sere hills dotted with cactus and scrub trees and blue, black mountains always hovering on the southern horizon signaling where Mexico was but there was more to this familiarity. Some turns of the road shaped the landscape into half-remembered backgrounds from Western movies.

When we got to Scott’s home, a sizeable place, traditional ranch layout, I mentioned this and he said that many films and television shows had been shot on the land we had driven through, some of which his family owned. Scott was several generations descended from a Gilded Age fortune made in Pittsburgh. Cattle ranching had been a diversification move by some grandparent or great-grandparent and he was the beneficiary of that.

I was totally in his hands. We drove to a motel and I checked in, then carried on to a new industrial park on the edge of town and turned into an enormous parking lot with dozens of tractor-trailers. At the far end was a gate leading into a little corral. An old horse was hitched to the fence munching a bit of scrub.

Across the corral was a little three-sided hut open to the benign elements. A couple of older men were sitting around drinking beer. Scott introduced me to Alex Amado, who owned the trucking business, and his brother-in-law, Vicente Carrasco. Alex handed us a couple of beers. Scott explained that I wanted to talk to people who had been living here a long time about changes along the border. Alex and Vicente sipped at their beers mulling this over for a while. After a few minutes of silence, Vicente began,

“John Wayne used to come here a lot.”

Pause.

“Yeah? What was he like?”

Pause, almost sotto voce:

“He was big, man.”

“Who was that other guy?” Alex asked no-one in particular, then answered his own question.

“Oh yeah! Ward Bond and the other guy, Chill Wills. They all used to come here to party. They could drink, man.”

Alex and Vicente gave deep, appreciative chuckles in remembrance.

Now this was interesting but not what I was looking to talk about. But after a week on the road I was beginning to learn that conversations along the border don’t proceed in a straight line from A to B to C. They meander, and if you’re patient, the conversation will eventually get to where you want it to go.

We sat for a while, reminiscing about old movie stars. A couple of roosters wandered over from the other side of the corral. Alex offered up another round of beers, and as we opened them he said:

“The maquiladores killed everything.”

It was the second time I had heard that phrase. The Maquiladora programme was instituted in 1965; the first step in what grew thrity years later into the North American Free Trade Agreement. It allowed American companies to ship parts to factories in Mexico. There the parts could be assembled into finished products and shipped back north to the US. No tariffs were paid either way. It was a good deal for Mexico because it meant job creation. It was a good deal for US companies because Mexican workers are paid a fraction of what Americans earn.

It was a bad deal for Nogales, Arizona and Nogales, Sonora. Alex Amado was certain of that.

“The place grew too fast. 30 years ago Nogales Sonora had maybe 20,000 people but now they can’t even count how many! They say 200,000 but its more. 400, maybe 500,000.”

The population explosion following the Maquilas had brought crime, crime which had spilled over to Nogales Arizona, according to Alex. In fact that day’s local newspaper, the Nogales International, carried on its front page a story about a $42 million cocaine seizure down by the big pink wall. The conversation continued to meander but underneath, the theme always seemed to be Mexico.

Alex and his brother in law Vicente remembered when the two Nogales seemed to exist almost independently of the two nations on whose border they sat. They were truly border people. Mexican and American blood and culture fused in them so they could feel at home in either country, and distant from them at the same time.

Vicente had been born in the Mexican Nogales, where his father had owned a restaurant and nightclub. It was gone now. And since he had moved north of the border—a move akin to crossing the street—he hardly ever returned. His contact with the new Nogales seemed to be primarily with the steady stream of Mexicans crossing without papers into the US. Everyone shook their heads and laughed sympathetically, thinking of the desperate naiveté of these would-be Americans. The other main story in that day’s edition of the Nogales International was of 95 illegal aliens being found in the back of a fruit truck heading north.

Despite his criticism, NAFTA had been very good for Alex Amado. He had built a business on the back of it. Auto parts would be trucked down from the industrial Midwest. The drivers did not want to drive on to the factories in Hermosillo a few hours drive deeper into Mexico. They spoke no Spanish and did not know the roads and, just as important, did not know how to deal with the authorities, whether customs officials or federal police or other “toll takers” along the way.

Alex set up a business with Mexican drivers who knew how to deal with these situations. Trucks would arrive in the big parking lot. Their trailers would be unitched and cabs with Mexican plates would then take them the rest of the way to be unloaded. Then the Mexican drivers would drive the empty trailers back to the Amado lot where they would be hooked up to the original cab and driven back north.

It was a neat business, an evolution of the Amado family’s activities stretching back at least into the mid-1800s. As Alex Amado told the story, there was no border in this part of North America it was all open range and his people had arrived as the railroad opened up Sonora to the world. They ranched and drove cattle and were the major clan in the region. There is even a town named for the family. I had driven through it on the way down from Tucson.

Around the time the Amado’s arrived in the region, Arizona became an American territory, split off from New Mexico. Alex spun a tall story about how the family became American: His grandfather happened to be in Tucson on business the day Arizona finally became a state, Valentine’s day 1912. So his grandfather had applied for American citizenship papers and that’s why the Amado family was American and not Mexican.

I bought the story hook, line and sinker. It probably wasn’t true. Anyone living in the Arizona territory was already a citizen. Perhaps Alex meant Arizona becoming a state was the first time anyone in his family had felt the need for written proof of citizenship. But the meaning of the story was clear. The border in this area meant nothing then. Most people living in the region spoke Spanish as a first language. They were American and Mexican and a line on a map designating to which country they paid taxes was not of primary importance to them.

Somebody noticed it was time to eat, but the conversation was too good to break up. Alex invited anyone who felt like it to come over to his house for dinner. We descended on Alex’s wife Espi, who was in the kitchen preparing enchiladas. Alex explained I was curious about life on the border. Espi didn’t miss a beat;

“The Maquilas killed everything.”

While assembling the enchiladas in a baking pan she reminisced;

“When I was a girl there was no wall. I could walk across from one side to the other swinging my little butt and nobody bothered me. Everybody knew who I was. But that was a long time ago.”

The doorbell rang and in walked a short, balding, garrulous fellow everyone called “Dr Carl”, Carl Meyer, the Amado’s family doctor for 4 decades, and Scott’s father-in-law.

“I’m his excuse,” he said, pointing to Scott, “So long as I’m here he can stay out as late as he wants and he won’t get in trouble.”

Everyone laughed. You should be getting the feeling now that laughter is a big part of life in Nogales. Usually, it’s laughter about the incredibly foolish things that lust can make a human being do. But almost any aspect of life can bring out a deep, from-the-inside chuckle. I mentioned this to Dr Carl, who agreed that laughter was a big part of life around here. His theory was that like most border areas in the world, the people around Nogales had to develop ways of dealing with a lot of strangers passing through, many of them inclined to be violent. Smiling, laughing, a bit of kindness to them, was part of keeping potential trouble at bay.

But there was something else according to the doctor. It had to do with the Mexican part of border culture. Mexicans have a fatalism born out of the country’s violent history.

“You’ll hear Mexicans say this phrase: Hijos de la chingada.”

Now it’s a vulgar phrase, much harsher in its meaning than the usual English translation: son of a bitch. The good doctor had his own translation, “It means I am the son of a rape. ” He said he most often heard it when people are caught in situations caused by their own stupidity, or forces beyond their control.

“The Mexicans have been raped twice in their history: first by the Spanish, then by the church.”

His theory was Mexicans accepted that somewhere forces greater than themselves would come and screw up their lives, so they had to laugh. The government is corrupt, what are you gonna do? Laugh. The federal police are shaking you down for a bribe. Laugh. Now the US with its free trade drive loomed over Mexico, changing their border towns beyond recognition. What do you do? Laugh.

“You know what they say?” Dr Carl asked. “Poor Mexico. So close to the US, so far from God.”

Everyone laughed.

Alex said, “Don’t believe a word he says," and everyone laughed again.

It should be added that over the last few hours a lot of beer had chased a lot of tequila which may have aided in the laughs.

I thought of the ending of the Wild Bunch. Robert Ryan outside the Mexican town where his friends have been slaughtered. The bounty hunters he has been forced to use as a private posse to track them have all been killed on their way back to Texas. Edmond O’Brien finds him sitting morose against an adobe wall. O’Brien invites Ryan to join a new gang he is organizing. "It ain’t like it used to be, but it’ll do.”

Soon they are laughing at the sheer insanity of it all. And as a Mexican corrido plays there is a montage of individual shots of each member of the Wild Bunch, as they were in life, roaring with laughter. I’d always thought Sam Peckinpah had overdone it with that ending but sitting, eating and drinking with these border people I realized he was simply documenting their worldview.

The house began to smell of home cooking as the enchiladas baked away. Others came in and out—Alex’s teenage grandson and granddaughter and her boyfriend. It was a spontaneous party, and I got the feeling it happened all the time. I heard wonderful stories about men and women, full of hilarious painful truths about marriage and love—and I can’t tell you one of them. They were just too bawdy. But each one provoked roars of gut-deep laughter.

The next day, Alex arranged for his business partner—who lived in Nogales, Sonora—to take me around the Mexican side. The fellow’s name was Carlos Shiels. Carlos wanted to show me the one thing the Mexican government had done to try and alleviate the overcrowding of the city. We drove to another hillside that was covered in neat rows with new houses. From a distance, they looked nice, but up close they were tiny. Mexicans have large families, Shiels pointe out, and these houses would be crowded if two adults lived in them. They were basically useless. You had to laugh.

We stopped at a cantina just off the main plaza for a beer. I asked him about the people I had seen crowded along the Mexican side of the wall, living in makeshift tents. Who were they?

“Illegals, hoping to get into the US. Looking for a coyote to take them in.”

“Why don’t they just walk over, like everybody else, and then get on a bus north?”

He shrugged.

“They don’t know better. Maybe they don’t even have Mexican papers. They come from the South, Chiapas. They’re Mayan. Look at their faces.”

They did look different, shorter with round faces. Not like Carlos who was tall and rangily built with a sharp, aquiline nose.

“Me, I’m Apache.”

Did he ever consider moving over the border and becoming American? Absolutely not. He knew too many people, friends and family, who had made the move and seen their children and grandchildren become unmoored. Not accepted as American and no longer fully Mexican, the kids have trouble adjusting in school and just generally finding an identity. In their adolescent search for a a sense of belonging to a place, gang life was a constant lure to young Mexican-Americans. He didn’t want that for his kids.

Sunday morning I was invited back to the truck-lot corral for a carne asada It was a brisk morning and it felt good to stand around the fire Vicente was tending, waiting for just the right moment to put down the grill and fling some meat on it. I turned to Alex and said,

“You know, I was told this would happen if I visited Nogales. A guy near Yuma named Charlie Page said so.”

Alex nodded and seemed to be thinking of something.

Then I remembered Charlie Page had given me the name of his daughter and son-in-law in Nogales and their phone number and said to call if I made it to the town, and of course, I had lost the number. Since Alex seemed to know everybody I mentioned the family’s surname, Parra. He looked at me

“This guy you’re talking about is an old guy? Big? Kind of crazy?”

“Yeah.”

“I know him. The Parra’s. I’m godfather to his grandchildren.”

And we laughed at the coincidence and that wasn’t the only laughter about a grandfather this Sunday morning. An acquaintance in his 70s had been caught in a compromising situation with a young prostitute over the border the previous night. He was still in jail. The men shook their heads in sympathy with the family, for the embarrassment they must feel, then roared at the thought of the old goat chasing after young girls.

The meat was cooking over white hot coals of mesquite, clipped from one of the bushes growing in the dry hills surrounding the corral.

The carne asada is a Sunday ritual. Usually Alex’s grandchildren come around. They saddle up their horses and ride in the hills beyond the industrial estate, all the way over to the border. It’s a way of living that won’t endure much longer. In ten years, the hills where Alex and his grandchildren ride, with the growth of border trade, will be paved over. Alex’s grandchildren certainly won’t be able to ride them with their kids.

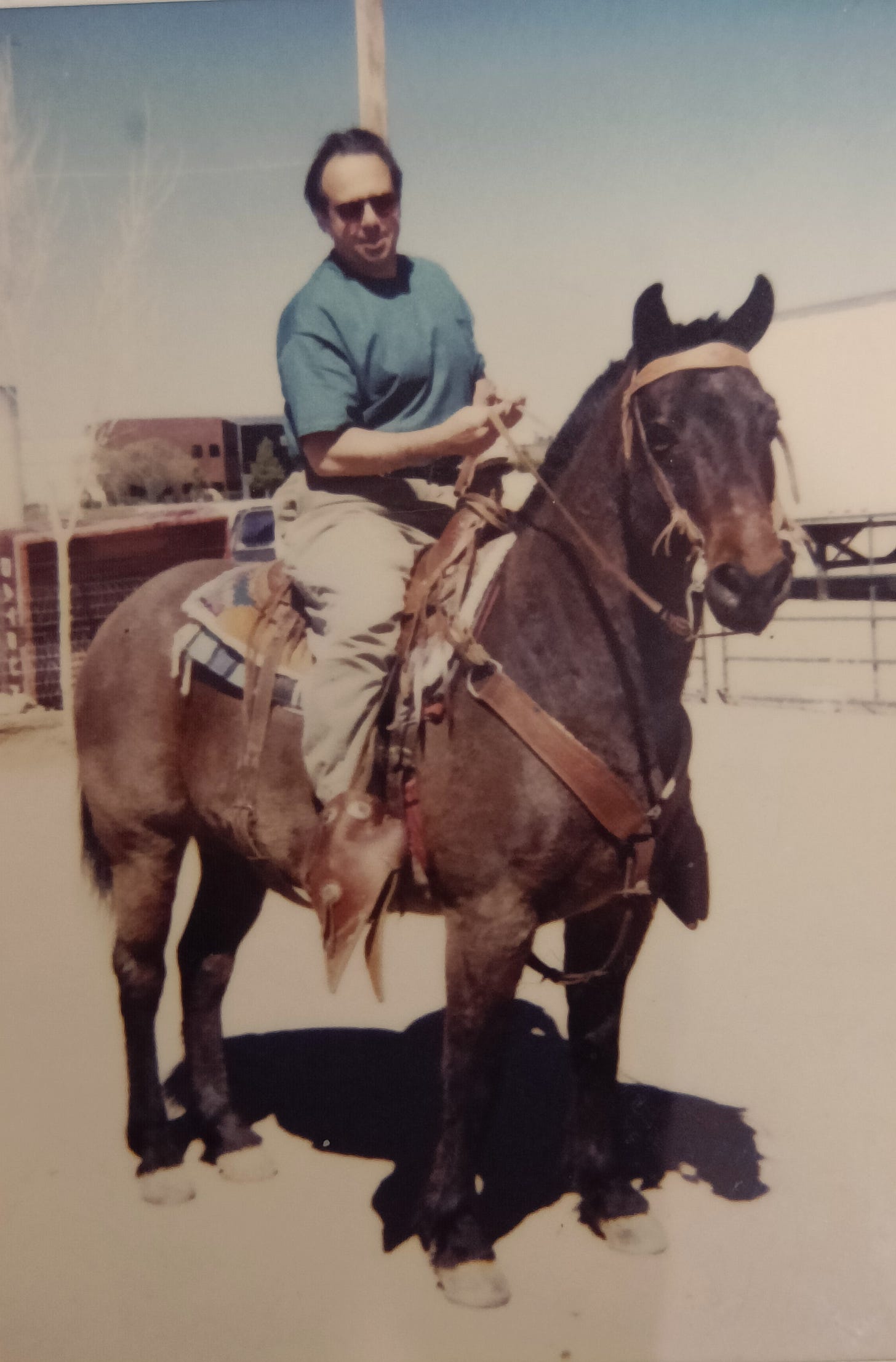

The man insisted I get up on a horse and take a turn around the corral. So I did.

The sun was sharp, the sky clear - it was getting time to go. I really didn’t want to. I’d been made to feel so welcome, I’d been shown such great hospitality, and didn’t really know how to thank Alex. All I could think to say was ‘You have a good life here.’ He walked me to my car and we shook hands. He didn’t say goodbye, Alex Amado said “Hasta luego.” Until whenever.

Whenever that may be.

This has been the seventh chapter of Part Four of History of a Calamity, the story of how America went from Victory in World War 2 to Donald Trump and Cold Civil War in a single lifetime … Mine, and possibly yours. The next chapter sees my 1998 Border Run come to an end in El Paso. Here’s an extract:

Towards the end of my journey along the border, in the town of Mesilla, New Mexico, a teacher gave me this history lesson:

Exactly 400 years ago in the spring of 1598, the Spanish explorer Don Juan de Oñate led a party of settlers from Mexico over a great river, the Rio Grande, and headed north to set up a colony. 600 people set forth with him to found “Nueva Mexico”, New Mexico. The settlers were accompanied by soldiers to protect their bodies, and priests to pray for their souls. They called the place they forded the Rio Grande, “El Paso del Rio del Norte”. Today the place is called El Paso, Texas.

The expedition carried on to the north, hugging the foothills of the mountains along the river plain. They stopped to bury their dead along the way. After travelling through mountain and desert for several hundred miles they set up a colony and called it Santa Fe. And all of this happened a quarter of a century before the Pilgrims founded Plymouth colony in what was not yet called Massachusetts.

And if you need to catch up on previous parts of my book, Part One, Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here: