CHAPTER TWO: THE 'BURBS

My Eden was made of concrete. It was not a place to go barefoot. There was black soot blowing from the coal chute and rustling old newspapers wrapped around God knows what and broken glass and dog mess underfoot. My paradise smelled like old beer. Its soundtrack was pure jazz, the incessant mechanical syncopation of New York: the wail of sirens, the shriek of subway brakes, the exhaust exhalations of buses stopping and starting on Manhattan’s avenues.

And then one day, through no sin of my own, I was cast out of paradise.

Not quite eight years old, I am descending a staircase in Penn Station—old, beautiful Penn Station—the Beaux-art masterpiece of Charles McKim whose entry hall is modeled on the baths of Caracalla in Rome.

Step by step through shafts of light slicing through the glass canopy roof, illuminating motes of dust mingling with the sinuous flight of cigarette smoke and steam from coffee machines.

Holding on to the gleaming brass banister all the way down to the platform, slightly beaten up silver cars, curved and aerodynamic, magnificent representatives of a style whose name I would learn much later: Art Deco. My destination is Philadelphia. My parents are already there.

The soundscape is disorienting. The objects I’m looking at are clear, the noise they make seem to be coming from a thousand miles away as the soundwaves rise up 150 feet from the track level to roll along the glass and wrought iron ceiling

I have an eye on my grandparents, laden with boxes of food and luggage as we go down the staircase.

Light and echo - a scene of irrevocable departure. Orson Welles borrowed the Penn Station effect in his flawed masterpiece, The Magnificent Ambersons, for the scene where Uncle Jack stands in a station to say good bye to his nephew George.

“I've always been fond of you, Georgie. I can't say I've always liked ya. But we all spoiled you terribly when you were a boy.” Then he disappears into a shaft of light. Whenever I watch the movie it reminds me of that day when one possible life ended and another began.

My new world was a place of swollen greenery and crabgrass and the smell of feral animal excrement rotting under piles of decaying leaves in the woods out the backdoor. Pollen and semi-tropical humidity irritated my eyes and caused a constant perspiration and chafing.

And an anxiety-inducing absence of noise.

That’s memory speaking.

Objectively, this environment to which I had been removed without consultation really wasn’t a bad place, Penn Valley, an unincorporated section of Narberth, Pa. eight miles from Center City Philadelphia.

It was very pretty. Our house, one of several dozen of similar size and shape, was midway along Green Tree Lane just before it sloped downhill. From the street outside I could look north over the Schuylkill river valley to a picturesque old milltown, row houses rising up the opposite hillside: Manayunk, on the Philadelphia side of the river. I could hear, but not see, the freight trains rumbling west through the Flat Rock Tunnel, one of the engineering marvels of 1840, 940 feet blasted through a solid rock bluff jutting towards the river.

Our unfenced back lawn ended abruptly and then fell steeply into thick woods. A family of deer could be seen there from time to time.

The social environment took more time to adjust to. At Robin Run day camp, to which my parents sent me that humid summer, I spent a lot of time on my own. A chubby fish out of water. It was the same in my new neighbourhood. On Green Tree Lane the neighbours all seemed to have male children roughly my age but they were very different from my friends in New York.

We couldn’t talk dinosaurs because they hadn’t been to the Museum of Natural History even once, much less a couple of times a month. Broadway meant nothing to them. They couldn’t sing Rodgers and Hammerstein songs, didn’t really know who they were. That was girls’ stuff.

We couldn’t talk sports because I had not had time to develop an interest in the local baseball team, the Phillies, and didn’t particularly want to. They were awful. My team, the New York Giants, had one of the best players in the game, Willie Mays, and had won the World Series a few years previously. The Phillies hadn’t won the World Series in their entire history.

The summer passed and then came the start of school. This put psychological pressure on my mother, who was having her own difficulties adjusting to the new environment.

On an early visit to Al the Barber in Narberth, Al called over his shoulder while working on my head, “Lady, your son’s got a tick in his scalp.”

“AHHHHHHHHHHHHHH , do something!”

She nearly fainted. Al poked and prodded with a tweezer and pried the little parasite out, showed it to her, then disinfected the wound with a bit of witch hazel while my mother recovered herself. Writing these words I’m still embarrassed.

My mother didn’t know what the country dress code was and sent me off on the first day of school in shorts. I was the only kid showing off his knees that day. Decades later I was still being teased about it by those who were there.

There was one other new thing to adjust to at Belmont Hills Elementary School: anti-Semitism.

The first time I was called a “Jew” with malicious intent was a few weeks after the school year started. It came as a surprise. In New York City everyone was Jewish. I thought the President was Jewish. Well, Eisenhower sounded Jewish to me.

Until that moment in the playground the word Jew had simply been one of the words and phrases, like “Mike,” “son,” and “114 East 90th Street,” whose meanings were slowly building up into a sense of who I was.

Whoever called me a “Jew” didn’t accompany the word with a shove or a punch, but the way the word was bitten off and barked contained enough implicit violence to make it clear that it was a bad thing. I simply didn’t know how to respond. I was the new kid in class, bewildered by the provincial environment, overweight, incorrectly dressed for the new suburban life and therefore struggling on a wide range of fronts to avoid being singled out for ridicule.

After a few months I had managed to blend in so the next time someone barked “Jew” at me I was still surprised. It was not like I wore a yarmulke or any other outward manifestation of Jewishness. I had just been typed and there was no getting away from that. Before too long I learned I was a “mockey” and a “kike” as well as a “Jew.” And with the help of the adults in my world I learned the boys calling me names were “Wops” and “Dagos” and “Micks.”

By American measures the Second World War is ancient history so it is easy to forget that, in addition to its horrors, the War liberated a generation of immigrants who had grown up in the Depression with little or no prospects for a better life. The conflict did more to break down class barriers and shake the society up than any of the New Deal’s economic plans.

World War II was a tontine and the winners were the second-generation immigrants raised in ghettoized city neighborhoods who didn’t get killed. In the service, the men had a chance to meet people from other strata of society, make connections and build the social capital that made it possible to find the means to open businesses after the war. The G.I. bill educated them and created the opportunity to achieve professional qualifications. These veterans quickly began to acquire wealth, and by the 1950′s new suburbs were being thrown up to give them a chance to get out of the city and breathe clean country air.

Regardless of ethnic background when people did move to the suburbs they stuck to their own kind recreating the security in numbers feeling of the old neighborhood. In Philadelphia, many Jews moved to suburban locations barely over the city line. Penn Valley was one. It was just adjacent to Belmont Hills a working class neighborhood that rolled down the steep ridge to the Schuylkill. The Hill was a twin to Manayunk across the river.

Belmont Hills was similar to hundreds of mill towns throughout the northeast in topography, architecture and ethnic structure: mostly Italian and Irish with a few Germans and one or two French Canadians who had drifted south; all staunchly Catholic. Their lives were based around employment in the small factories that still lined the Schuylkill in the 1950′s.

And because of the way the Lower Merion School District boundary lines were drawn the children of the new middle-class Jews and the working class Catholics were thrown together. It was like 18th century Europe from Alsace to Galicia without the money-lending. There was mutual suspicion and occasional exploration between the two groups and a childlike acceptance that “they” were different. But a couple of times a year the tension in that difference boiled over in the schoolyard or an unsupervised moment in the classroom.

“Jew!”

“Wop!”

“Mockey!”

“Dago!”

“Kike!”

“Guinea!”

Then shoving and ten-year old fisticuffs until a teacher intervened..

Anti-Semitism is a complex phenomenon. It wasn’t simply Jew hatred being expressed in these occasional outbursts but envy and fear of any people who were different – and wealthier.

Whatever the reason, being regularly called a Jew and the threat of violence that hovered in the air with it continued to add to my sense of who I was. I was a very diligent student at Hebrew school but not very religious. My sense of being Jewish came as much from the nasty way in which I was periodically reminded of my difference from the Catholic kids of Belmont Hills as it did from rituals of religion.

There were other ways, of course.

In spring I occasionally walked the mile or so home from school to Penn Valley through the Hill. Sometimes I would be accompanied by guys from that neighborhood to the boundary of my own. We would talk about the things eleven and twelve year old boys talk about: toughness, strength, whose father was meaner. For 60 years a fragment of a conversation with Joey Fital and Joe Roscioli has been stuck to the inside of my skull like a barnacle. We were bragging on who got the worst whippings, comparing our respective old man’s belt preferences, how many smacks we got and for what offences. I tried to uphold the honor of the Jews in this conversation, exaggerating the number of times I got the strap and the offenses that led to punishment but when Joey Fital asked whether my old man used the buckle like his did I had to remain silent. My father was a reluctant flogger at best and I couldn’t exaggerate more than I already had.

Until that conversation I had known Joey mostly as one of the leaders of the anti-Semitic chorus, now we had a different understanding of each other. It didn’t end his occasional ugly use of the J-word but that conversation, and others like it, put it in a different context.

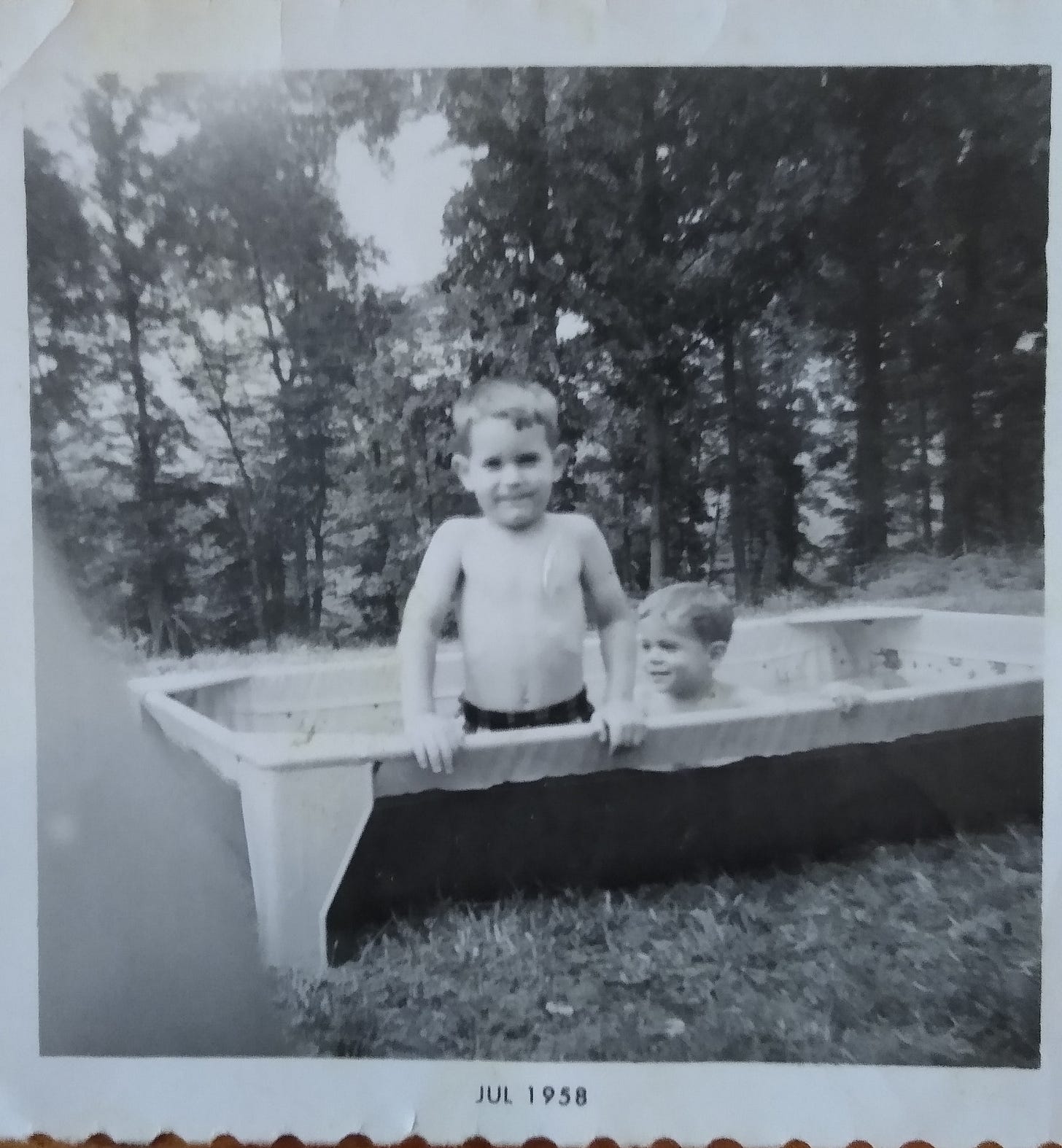

My younger brothers have less happy memories. One day they wandered into some woods near our house and crossed paths with two older kids from the Hill.

“Didn’t you see the sign?” one of the older boys asked.

“What sign?’

“No Jews Allowed.”

Then one of the Hill kids held a knife to my youngest brother’s throat and said the Jews killed Christ and they would kill him, unless my middle brother promised to renounce Judaism and apologize.

My period of adjustment to the suburbs was traumatic but brief - I found friends quickly and if museum visits were no longer my regular weekend activity, then hours of shooting baskets and playing improvised ball games and discovering with my best friend at the age of 12 someone’s stash of nudie magazines in an abandoned refrigerator in the woods out back made up for it.

I’m not sure America has ever fully adjusted to becoming a suburban society. The population movement in the decade from 1950 to 1960 was massive and profound. It was the equivalent of the Western expansion after the Civil War, only it was accomplished without a shot being fired, or an indigenous person resettled.

In a single decade the suburban population grew from 35 to 84 million, a rise of 144%.

It wasn’t just people who were relocating, businesses and institutions that defined cities were moving as well. The same year I left New York, my baseball team the Giants, left for San Francisco. Another New York team, the Brooklyn Dodgers began playing in Los Angeles - the city that is all suburb. The effect of their departure was seismic. New York was the center of my universe but it was also the center of American culture - no other city had three professional baseball teams. All but one World Series in the 1950’s to that point had been won by New York’s teams.

But the Dodgers and Giants departures tore a hole in the city’s self-image. Who would leave the center of the universe? No one. But if the city was no longer the center why stay?

The 1950’s were the first decade in the city’s 350-year history when New York lost population.

The Big Apple wasn’t the only metropolis that began shrinking. Chicago and Detroit also lost population. Los Angeles, the Big Nowhere, replaced Philadelphia as America’s third largest city. Houston, which didn’t have a baseball team yet, became one of the ten largest cities in the US by building itself on the Los Angeles model: annexing surrounding townships and land for development and becoming an enormous suburb built around a business center where no one lived.

In that light my dispossession is not such a personal tragedy, it is just one part of a trend.

The rapid suburbanisation of the country is reflected in other ways. In 1950 33.3% of Americans, a precise third, worked in white collar jobs, 46.6% wore blue collars. By 1960, that had nearly reversed - 43.3% were white collar 36.5 were blue collar … that trend has continued.

Two things drove the suburbanization of America. The first, often remarked on, is the automobile. There were already a lot of cars on the road before World War 2. But after the war car ownership became standard for most American households.

Highway building became a necessary obsession in the 1950’s which culminated in the creation of the interstate highway system - 41,000 miles of new superhighways. These roads weren’t built just to accomodate the population movement out of the city tot he suburbs. In 1956, when President Eisenhower signed the federal bill creating the interstate system he mentioned the real reason, “In case of atomic attack on our key cities, the road network must permit quick evacuation of target areas.”

The Interstate system took 35 years to complete. The Soviet Union collapsed the year it was finished. Given how many decades of traffic jams the construction created, it’s a good thing the Soviets decided to keep their missiles in their silos. Even with a two-day warning there is no way New York or Philadelphia could have been evacuated.

The second reason rapid suburbanization was possible was land. There’s a lot of it in America and it was reasonably cheap for developers to buy.

It is comparatively easy to make a fortune in the US —if the zeitgeist is favourable and a person is singleminded—but this wealth is difficult for families to hold on to. In Philadelphia, the men who made the fortunes of the first Gilded Age in railroads, finance, oil and steel built baronial estates on large tracts of land in the hilly, wooded country along the Pennsylvania Railroad’s main line west towards Pittsburgh.

Two generations later these families, cursed with the psychopathologies associated with inherited wealth and unable to pay taxes on the estates, began selling up to real estate developers.

The general area we lived in was still called the Main Line. Demand for more development land was incessant.

Just at the edge of our suburbs the farms began. Years later, when I had my driver’s license and adolescent angst overwhelmed me, I would drive the traffic free back roads among the farms at shocking speeds. But eventually, the farmers realized you could make more money selling your land than farming it. Another ring of suburbs was added around Philadelphia and then another and today the roads are crowded to a standstill. Driving 90 mph on route 926, a two-lane blacktop road, is no longer dangerous, it is impossible. You might be able to do the 45-mph speed limit occasionally, but it is generally too crowded for even that.

A third reason for rapid suburbanization was the war. All manner of pre-fab construction techniques and just in time delivery systems had been invented to build massive military installations at the drop of a hat. Now these were applied to suburban development.

IN 1947, the first suburb built this way was erected in Hempstead, Long Island, just over the city line from New York, by the firm Levitt & Sons. It was called Levittown.

A second Levittown was built in the Philadelphia suburbs between 1951-58. In that seven year period 17,311 single family homes were erected connected by 171 miles of road.

Levittown houses were cheap. You could get a low-interest federal government mortgage to buy one and the houses sold within days of being offered. It’s easy to understand why they were so popular.

You come back from war, living with Mom & Dad isn’t a good option. You’ve lost a few years of the prime of your life. You’ve seen death and want to get on with procreating. Levittown or similar developments fit the bill.

The company’s president, William Levitt’s portrait was on the cover of Time Magazine in the middle year of the American century, with the headline “For Sale: A New Way of Life”.

The rush towards the new didn’t necessarily mean a rush towards the better. Levittown and other new developments helped people segregate among their own ethnic and religious groups. Penn Valley was known as Little Jerusalem.

William Levitt was a Democrat and lobbied hard for racial equality but he would not rent or sell to African-Americans. Levitt told an interviewer, “We can solve a housing problem, or we can try to solve a racial problem. But we cannot combine the two.”

The cheek by jowlness of city-life was lost. In the city, you might live on a block that was mostly Jewish or Irish or Italian or Black but when you went to the corner shop or walked to school you crossed boundaries and ran into those from different ethnic or socioeconomic backgrounds in the street. It wasn’t always pleasant as my walks home through Belmont Hills demonstrate. But those walks were only occasional, most journeys in the suburbs were by car.

The automobile reinforced the suburban social separateness. It was your house on four wheels. From driveway to office to grocery store to shopping center to cinema to office to doctor’s appointment to orthodontist to school to girlfriend’s home for coffee, to your kid’s playdate. It was probable you would never encounter anyone who was different, no possibility of an interaction with another kind of life.

Less easy to describe with statistics was the effect of generational disruption within families of moves to the suburbs. Many of those moving out of the city came from ethnic communities where family closeness was part of the social environment. Generations lived in close proximity, cousins wandered in and out of each other’s houses. This intimacy was both continuity from the old country and a necessary defense network against the dangers of being new in the New World.

The population shift to the suburbs of the American mid-century completely disrupted those chains of family and ethnic connection. It was the second epoch defining demographic change my grandparents were living through. They had been part of the non-English speaking immigration wave that washed through Ellis Island and other ports of entry at the start of the Twentieth century.

Closeness was wired into them. My paternal grandmother was one of five sisters, all but one of them lived within a few blocks of each other in the Bronx. Their parents, my great-grandparents, lived in the same neighborhood and the sisters were available to care for them when they reached old age. Later in life, they would all retire to within a few blocks of each other in Hallandale, Florida. They are all buried within a few feet of each other at one of the Jewish necropolises in Paramus NJ.

In New York on summer Sundays, the whole crew, grandparents and great-aunts and uncles, would pile into Uncle Charlie’s Pontiac and take my brother and I to Jones Beach or Coney Island.

The move to Penn Valley completely disrupted this generational connection. It was barely a two hour drive from the Bronx to our house but it was as if we had left one country for another.

At first, every six weeks or so, my father’s family would drive down bringing the delicatessen and challah and cheese danish they were certain you could not get in Philadelphia. We drove to them for Passover. Then slowly but surely the visits became less frequent. We were the first to move from New York to the suburbs, soon everyone in my father’s generation of the family had done so. There were too many children and grandchildren to visit. There were a couple of attempts at an annual get together at the Raleigh Hotel in the Catskills. Then the idea of family and cousins as the final line of defense became something vestigial.

My maternal grandmother hardly ever visited. My mother was an only child and beyond that a child of divorce. She had a 1970s childhood in the late 1920s. My grandmother put enormous pressure on her to come back to New York for visits and used every psychological power game in the book to make my mother feel guilty that she could not because she had to take care of us. In this, my grandmother succeeded.

Isolation was inherent in this bright, new, suburban world. Physical and psychological. Who could possibly find anything to complain about on a half-acre with a new or relatively new home of your own. If you weren’t happy that was clearly your problem.

My mother suffered terribly in this environment. She was a true New Yorker. For her, the best life was in the street, at the soda fountain at Pat and Al’s drug store on Lexington Avenue having a milk shake with a friend. It was pushing an infant in a pram while walking a toddler nine blocks to pick seven year old me up at P.S. 6 on a spring day. Now there was nowhere within walking distance and she could not, would not learn to drive. It was her form of rebellion against her exile.

By 1960 she had four children under ten to look after while my father sought the bubble reputation in the surgical theatre and in the hospital laboratory. He worked on developing oral contraceptives when my mother was bearing children and infertility treatments after she had stopped. She didn’t see much of him during the week. He was out of the house by 6 most mornings, and often had meetings on weeknights.

Meanwhile, her mother was slamming the phone down on her. Her loneliness deepened. Severe depression darkened many of my mother’s days.

And if I’m honest, living in the shadow of her pain shaped my dark view of the ‘burbs. Til the day he died, I joked with my father that if he hadn’t moved us out of New York I would have become a corporate lawyer and been able to retire him in the comfort to which he was already accustomed but could not afford.

New York became my escape. Five years after my eviction from Paradise I was allowed to start riding the train back to Penn Station on my own to visit my grandparents.

But by then the station had become a demolition site. People were flying and driving. They were no longer taking trains to travel. The Pennsylvania Railroad was going bust and sold off its crown jewel.

Jackhammers and dust and temporary exits and entrances of plywood had replaced the Beaux-Arts fantasy through which I had left the city of my birth. The great building was knocked down to be replaced by a new Madison Square Garden, possibly the ugliest piece of civic architecture ever built in America.

Construction on Penn Station began in 1904, the year my maternal grandmother’s entry into the US is noted at Ellis Island. The station opened in 1910, the year my paternal grandmother’s name is inscribed in the arrivals book. 52 years later the building was knocked down for no particular reason except the short term profit that real estate developers could make.

Penn Station was a symbol of America in its first flush of global economic power, now it was being erased. The New York Times architecture critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, wrote in an article headlined, “How to Kill Off a City:”

“Surely there could be no more curious confusion of values than this, no clearer evidence of the current emphasis on expedient commercial advantage over all other considerations.”

"The tragedy is that our own times not only could not produce such a building, but cannot even maintain it. "

But in the suburbs such fine considerations were of no importance. Living separated from one another on little private plots of land while going here and there in cars, civic space, the idea of a public square, the “common,” was being lost. And as for cities, who cares? Drive-in, make your living, drive out.

Huxtable wrote:

“It’s time we stopped talking about our affluent society. We are an impoverished society. It is a poor society … that has no money for anything except expressways to rush people out of our dull and deteriorating cities.”

It is probably too much of a symbolic burden to place on a single act of architectural vandalism but the destruction of Penn Station does seem an early step along the road to America’s catastrophe. Huxtable was prophetic. New York and other cities would rapidly deteriorate then fall apart, society’s center would not hold.

New York’s population would continue to shrink as the city and slowly headed towards a calamity that would arrive in a curtain of flame a decade later. It was a calamity that I would experience at a cellular level, but I am getting ahead of the story. In the suburbs life was sweet and the idea that America might ever go off the rails impossible to imagine.

(Now read on to Chapter Three)

The Financial Times says:

So was Penn Valley a Levittown? You know who else has written eloquently about growing up the suburbs and a Levittown in particular? Bill Griffith, creator of Zippy, esp. in his graphic memoir Invisible Ink. PS: Chris feels exactly the same way about being snatched out of grim postwar central London and exiled to the the green suburbs of Middlesex.

I wish I had your memory Michael - wonderful stuff. Have you ever visited Narberth in Wales? You should

one day ...rather different proposition ...!