CHAPTER TWELVE: THE PRIMACY OF THE INSTANT

Part Three of History of a Calamity: It's a Hack's Life

Journalism is a calling, gathering news and information, is what we do. But journalists need to be paid. People value the information we gather, so the news became a business. And in the tension between a calling and a business lies the unintentionally destructive force that American journalism has become in the decades I have spent working as a reporter, a hack.

Good journalists want to be first. The news business has been built on using new technology to be first going back at least into the mid 19th century. Julius Reuter laid down the template. He built his eponymous news business on the era’s new technology: the telegraph. And where wires weren’t yet strung he used carrier pigeons to bridge the gap.

Reuter’s coup was setting up a link from the far southwest of Ireland to Dublin and then on to London. He paid people in New York, working at what is today the Associated Press, to put news reports in waterproof canisters that were passed from ships heading onward to Britain onto small tenders based in the harbor town of Crookhaven. From there the news was telegraphed onward to London.

His subscribers had news from America about the Civil War and the country’s politics and state of business before anyone else. That knowledge allowed them to speculate on London’s stock exchanges and commodity exchanges—cotton trade was disrupted by the war—with considerably less risk. It was a service worth paying for.

News, business and speed have always been linked.

On Sunday, June 1st 1980, a new iteration of journalism, technology and the news business was launched from a disused country club clubhouse in suburban Atlanta Georgia. CNN, The Cable News Network, debuted with a speech from its founder, Ted Turner.

In 1980, television news in America was the province of the the three major networks—ABC, CBS and NBC and their affilliates. By mutual agreement news was confined to a main half-hour bulletin provided by the network at around dinner time - 22 minutes or so of actual reporting and 8 minutes of commercials. Before this national bulletin the affiliates ran an hour or even 90 minutes, including ads, of local news. Some of it was about important events but much of it was light features.

The arrangement worked for most everyone. Viewers had not been clamouring for 24 hour television news, nor had the professionals.

The basic question: what if nothing newsworthy is happening? was pretty daunting to journalists. Another question: how will we pay for this? was daunting to news business people.

But Ted Turner’s situation was entirely different from that of the three networks. Following his father’s suicide, he had inherited the family’s outdoor billboard advertising company. it was 1963 and Turner was in his mid-20s. The company was based in the South and the young entrepreneur grew the enterprise and used the profits to buy a small television station in Atlanta, Georgia.

Fascinated by the possibilities new technology offered for distributing programs outside the network and affiliate cartel, Turner started broadcasting his station’s offerings via satellite to cable television systems.

Satellite cable television was the new technology of the 1970s, as the telegraph was when Julius Reuter began his business. But it wasn’t ubiquitous. To get customers to sign up for cable he had to offer new programming.

At a meeting of satellite entrepreneurs he met Reese Schonfeld. Schonfeld came from the news picture business. After taking his law degree from Columbia he had gone to work for Movietone News, the provider of the newsreels that used to play before feature films at the cinema. When daily television news made newsreels obsolete, Schonfeld had gone to work for United Press International Television News overseeing news footage coming in from all over the world. Like Turner he was fascinated by the possibility that satellite delivery offered for almost instant transmission of news footage.

Turner and Schonfeld went to work brainstorming a way to use the new technology to create a 24-hour television news channel. Turner figured out the finance, Schonfeld worked at creating the logistics and format for getting all the incoming visual reports into a coherent shape for viewers.

So CNN came to life.

CNNs first hour on air was filled with standard fare for local news in America: a couple of shootings. But luckily for the network one of those who had been shot was civil rights leader Vernon Jordan who had been attending a dinner in Ft. Wayne Indiana for the Urban League, a civil rights organization. Jordan was friendly with the President, Jimmy Carter, who was also from Georgia and also friendly with Ted Turner.

Carter flew to Indiana to visit Jordan in the hospital and when he left his friend’s bedside he met with reporters gathered in the hospital corridor. Carter was a dull speaker. For that evening’s network newscasts a soundbite dredged out of the impromptu press conference was enough. Not for CNN. They ran the whole thing live. I doubt any other broadcast outlet did.

Not many people saw those first hours of CNN. America’s cable television business is stupefyingly complex and because of those complexities CNN could only reach a maximum of 15 million viewers. It did not come close to getting them all to watch. But Turner kept plugging along, burning through startup cash at a rate of $2 million a month. The history books say CNN was derided by its television and print competitors as Chicken Noodle News, That was a euphemism. Many news veterans called it Chickenshit News Network.

Then on March 30th 1981 CNN had a chance to show what 24 hour news could do.

President Ronald Reagan was shot while walking to his car after giving a speech at the Washington Hilton hotel. CNN was first to break the news and get cameras to the scene.

At The Washington Post, a few miles away from where the shooting occurred, televisions were crammed into TV critic Tom Shales’ tiny office in the Style section as the big networks caught up to the story. Shales watched all of them at once, and started making notes for his review of the coverage while editors and reporters hung out in the doorway, kibitzing, checking in for details.

Shales review would say

Whether or not the surplus of misinformation doled out yesterday is an inevitable byproduct of an information-addicted, ready-access environment remains to be discussed.

Despite Shales criticism of ready-accessed, virtually unreported, organized and edited information being doled out to “gotta know right now” addicts, something fundamental changed about journalism in coverage of that event:

The Primacy of the instant was elevated by CNN. The real time work of reporters was compressed to a degree that defied all previous rules of good journalistic practice.

Being first was one thing, just opening a camera up and staying with a single story for hours was unheard of. Essentially that’s what CNN would do for 29 consecutive hours after the shooting. It got a crew to the home of the shooter, John Hinckley, and the store where he apparently bought the gun.

Shales did not write about CNN’s obsessive coverage because CNN was not available in Washington.

I know this because I watched the scene outside his office unfold. I had recently started a job in the Style section of The Washington Post as a copy aide—the title used to be copy boy but as early as 1981 gendered titles were on their way out at the Post.

I was far and away the oldest copy aide on the floor. After two and a half years in New York driving a cab and acting for free, followed by two and a half years of acting for pay and collecting unemployment between jobs I had reached my self-imposed five year time limit to make it in the theatre. I hadn’t succeeded, so I decided to move on. Journalism was something I knew about and even had paid experience in.

In high school I had covered sports for the local suburban newspaper, the Main Line Times. As part of Antioch College’s “co-op programme” where the academic year was broken up by requiring students to take a real world job, I had worked as a copy boy at The American Banker, a New York financial daily.

For reasons only my several therapists know and would not divulge I had walked away from journalism as a profession. Journalism combined two things I possessed in abundance—curiosity and facility with words—along with the irregular working hours I craved. Being a reporter was my fate and now, at the age of thirty, I was prepared to accept it.

A friend in Washington DC mentioned the Post was always looking for copy aides if I was willing to start at the bottom. I had no choice. By luck the woman in charge of hiring copy aides, Nancy Brucker, had a beloved cousin who had just embarked on the actor’s life in New York. He was making rent waiting tables. When I told her about my years driving the cab and auditioning for parts she took pity on me. The job she offered was a swing shift, working from lunch until 8 in the evening: answering phones, pigeon-holing mail, and taking reporters’ dictation from the field. There was also the prospect of occasionally writing the daily personalities column—after I had proved myself.

The money was abysmal. At a time when most people my age and social class were working on a second child and a first mortgage, I would be earning around what I made as a cab driver. But it was The Washington Post and there was the possibility of the occasional byline. And, to be honest, while there are second acts in American life—actually there are third, fourth and Shakespearean fifth acts in American life— each new act starts with the realization that beggars can’t be choosers.

In 1981, when I started working there, The Washington Post was at the zenith of its post-Watergate fame. The whole episode, from failed burglary of the Democratic National Committe headquarters in the Watergate complex to Richard Nixon’s resignation, was not even a decade in the past.

Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward’s book about Watergate, “All The President’s Men”, had been turned into an Oscar winning film. Bernstein had moved on but Woodward was still to be seen working in the newsroom.

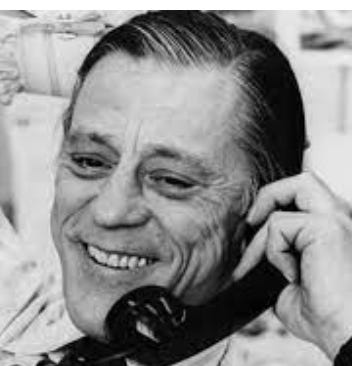

Ben Bradlee, the Post’s editor, was one of the most famous people in the country. People who worked at the Post walked with a certain swagger.

When I started in American journalism forty years ago, print journalists were first among equals. Television news was still a comparatively recent phenomenon and had already started the journey towards slick presentation over journalistic depth that has come to define it.

Newspapers were embedded in their communities in a way television could not be. They delivered not just reporting of the previous day’s events but notices about local stuff: births, deaths, school plays, and advertisements with coupons for local business. Nearly every household took one, if only for the coupons.

Although their national distribution was minimal, the big time papers—the Post, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Wall Street Journal—were the unassailed agenda setters. The families that owned these institutions were a lay aristocracy, handing their news businesses down through the generations

My beginning coincided with an age of transition in the practice of journalism. The primacy of the instant represented by CNN was complemented by a speeding up of the production processes of journalism. Computers were replacing typewriters and typesetting. In the first months at the Post I physically ran pages down to the typesetters so they could lay them out before they were sent on to the printing press. That came to an end a few months later.

The computers were primitive, the screens tiny. The programmes they ran required ridiculously complex sequences of keystrokes to do a simple task like highlight a paragraph then cut and paste it somewhere else in a story. Hit the wrong key and you were in trouble. The work day was punctuated with groans, muttered “oh nos”, and actual screams as blocks of copy disappeared never to be found again.

There weren’t enough computers to go around in the Style section. The food editor, Phylis Richman, and the fashion editor, Nina Hyde, had to share one and part of my job was to negotiate the deadline handover.

Nina, it’s 3 o’clock it’s Phyllis’s turn now.

Oh please I just need ten more minutes.

Nina would turn with pleading eyes to Phyllis who was unmoved, the pleading turned to dagger eyes at me as I got down on my hands and knees, crawled under her desk unplugged the computer, which was on a cheap metal cart and wobble-wheeled it over to Phyllis.

Computers were an obvious manifestion of the changing world of journalism and the news business.

Less obvious was the transition in American society that would see the primacy of newspapers in national life and the families that owned them diminished. Ronald Reagan, at that point the oldest man ever elected to the Presidency, was an indicator of the coming change

Small example: The president in those golden years after the war was rarely seen. Not because Presidents crave the shadows but because they have executive jobs and most of their days are spent in meetings. But after CNN arrived the President became a constant presence. Legislation signing ceremonies, events of watching paint dry dullness, became an opportunity to run pictures of something “new” for CNN.

CNN and Reagan were made for each other. The network would cut to Reagan or any subsequent president striding to a helicopter on the White House South Lawn to go somewhere, anywhere: Camp David for the weekend, Andrews Air Force Base to catch a plane to an international conference or fly to Des Moines, Iowa to deliver a campaign speech.

These became occasions for CNN to run pictures while reporters filled in the time with speculation based on tidbits of gossip from “sources.”

“What are you hearing?” A studio anchor would ask. The truthful answer would have been, “You in my ear piece, Bernie.” But that’s not what anyone said.

By the 1980s the presidency was already called “Imperial,” now it had daily, real time imagery to go with the word.

It also had a president who could play the part. I started the job a few weeks before Ronald Reagan’s inauguration. It was a story made for Style. The Style Section was a Ben Bradlee innovation. It was set up in the late 60s to bring some colour to the very dull world of Washington. It combined culture, fashion, food, lifestyle with big profiles of the egos that dominate America's capitol.

At night reporters would fan out across the city to diplomatic receptions & political gatherings and report on them. The tone was very Vanity Fair. Bradlee’s uncle, Frank Crowninshield had been the first editor of Vanity Fair when it was founded by Condé Nast in 1914. But there was a touch of William Thackeray’s 19th century novel Vanity Fair as well in the writing found in Style. What the women wore, what the “important” men said on the record, what was overheard off the record. Gossip. Very quickly, in a company town, a mention, any mention in the Style section became a status symbol.

Status symbols were back with Reagan’s election. Style ran articles about traffic jams of private jets flown in from California for the Inauguration. The glitter and excess were described as a joyful change from the dour, turn down the thermostat presidency of Jimmy Carter. The headlines detailing the party-going scene inaugural weekend were delirious.

The Furs! The Food!

The Crowds! The Clout!

Inauguration night reporters trooped out in formal attire to do the Style thing: hang out, slyly observe and file reports from the field.

At a party thrown at the Four Seasons by the then president of NBC, Fred Silverman, Mary Battiata came across Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater sitting by himself in a quiet area away from the main ballroom. Reagan’s career as a Republican politician had been launched when he campaigned for Goldwater during the Arizonan’s ill-fated run for the presidency against Lyndon Johnson in 1964.

With the revolution he had been the standard bearer for now complete and a conservative Republican in the White House, Battiata asked Goldwater what he thought of all the partying going on around the Inauguration. Goldwater grumped,

Ostentatious. I've seen seven of them [inaugurations] and I say when you've got to pay $2000 for a limousine for four days, $7 to park, and $2.50 to check your coat at a time when most people in this country just can’t hack it, that's ostentatious."

Revealing offhand quotes set amongst descriptions of conspicuous consumption, that was the Style template.

The Post was a reflection of Bradlee.

Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was a patrician, bloodlines going back to Massachusetts Bay Colony on one side, family fortune made in 17th century New England seafaring on the other.

He carried himself like a commodore. Striding around the newsroom, rapping a knuckle on desks as he passed. Washington is, as Gore Vidal said, Hollywood for ugly people. Except in the case of Bradlee, handsome and charismatic as a Golden Age movie star.

He dressed the part. The editor wore bespoke shirts from Turnbull and Asser in London’s Jermyn Street with their distinctive white collars. High fliers or wannabe high fliers at the Post wore them as well. There were more white collars on display in the newsroom than at a convention of Anglican vicars.

It was an earnest, ambitious atmosphere at the Post. The cynicism of a big city paper was absent, no hacks were cranking out verbiage that would line bird cages at the Post. Philip Graham, the late publisher of the paper, reputedly said, “Journalism is the First Rough Draft of History”, and that’s what the reporters were writing.

It wasn’t all serious. The daily paper was encyclopedic and the Sports and Style sections were there to provide a bit of distraction and entertainment but the primary function in the newsroom was the serious business of reporting and summarizing the previous days events.

For a short period of time after Watergate, journalists and their readers understood that journalism has a function beyond merely telling people what happened the previous day. It has a civic function and part of being a good citizen meant reading the information—the truth—about their government that journalists dig out.

In addition, the extraordinary success of “All the President’s Men” demonstrated to the general public that journalism is a process that takes time, if for no other reason than to be sure you have the facts right.

And when you don’t get the facts right?

Ronald Reagan was shot about a mile away from where the Big Three networks had their news bureaus. There was no logistical problem getting reporters to the scene, yet throughout the afternoon the anchors in their studios relayed one incorrect fact after another.

The most crucial mistake was repeating for at least an hour after the event that Reagan had not been hit. When Frank Reynolds, anchoring ABCs coverage, was finally handed a piece of paper saying in fact, the President had been shot and was in surgery he looked into the camera and said, “All of this that we’ve been telling you is incorrect. We must redraw this tragedy in different terms.”

In Tom Shales’ review of the day’s coverage, after he noted how much misinformation had been pumped out, he went on to say:

“The news organizations of the three major networks are staffed and organized so that no effective system exists during coverage of a crisis of global import to screen out rumor, gossip, hysterical tale-telling, hearsay and tongue-wagging.”

Shales was being harsh. Such a system is not possible. I know this from experience. Twenty years later, on the morning of September 11th, 2001, I was hosting the NPR program, The Connection, an interview call-in show at the studios of WBUR in Boston. The program went out between 10 a.m. and 12 p.m. so I was live on air as the second tower came down.

Throughout the two-hours we were on the air producers rushed in with updated reports from Reuters, AP and other news wire services. Much of that information was incorrect. I did try and periodically remind listeners that the story would change, new facts—factual facts—would become known. I asked their indulgence for any mistakes those of us in the studio might be making.

But in a crisis people want news faster than it can be gathered, collated, edited, and then presented as a coherent report.

You can’t fast forward reality. Journalism is a process that takes time.

By 2001 the primacy of the instant ruled expectations. So errors proliferated throughout that dreadful day.

However, I am getting a little ahead of the story about how news media played into America’s calamity. This was foreshadowed in my first months at The Washington Post.

In August 1981, the Washington Star, the only other daily newspaper in town, stopped publishing. The Star was a brilliant paper but news is first and foremost a business and excellent journalism is only a small part of its business model.

The Star was a victim of the same seismic social changes that helped bring Reagan to the White House and CNN to television screens: suburbanization and the ubiquity of television screens.

It was an afternoon paper, and as more and more people commuted to work from the suburbs in their cars, there was no longer a need for something to read on the bus or train home. If you were interested in what had happened during the day there was the evening news on television, or if news broke during the day, there was CNN which was getting carried on more and more cable systems—and there was always a television close by on which to watch.

America’s afternoon papers were unable to sustain themselves against the changing reality of news consumption.

At the Post, meetings were held, editors ordered to compile lists of who on the Star’s staff should be offered a lifeline. There were many wonderful reporters and editors at the paper, more than the Post could hire.

There was a life and death excitement in the newsroom. It was a bit like being on a World War 2 rescue ship arriving at the scene of a U-boat attack and plucking comrades out of the sea.

The closure of The Washington Star was a glimpse into journalism’s future and my future as well. Being an excellent newspaper or news program would not be enough to keep the doors open nor would it keep good journalists employed. But it would be decades before I learned this the hard way. The thing about foreshadowing is you only recognize it in retrospect.

This is the first chapter of Part Three of History of a Calamity, the story of how America went from Victory in World War 2 to Donald Trump and Cold Civil War in a single lifetime … Mine.

If you need to catch up on previous parts of my book, Part One, Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here:

Notes/Sources

http://media-cmi.com/downloads/Sixty_Years_Daily_Newspaper_Circulation_Trends_050611.pdf

From where might a name like "Crowninshield" originate?