CHAPTER NINE: NIXON'S SATURDAY NIGHT MASSACRE

Is there a danger in victory? When you are discussing history, of course, there is. Victors are prone to complacency, which allows the vanquished—short of of the victors doing a Carthage on a place, utterly destroying it and sowing the ground with salt—a chance to rebuild and fight back.

Victors proclaim the end of history, when history, being essentially the story we tell each other about ourselves and our societies, will never really reach an end until humanity is ultimately extinguished.

One particular event of October 1973 heralded such a delusion of victory.

It unfolded on a Saturday night in Washington DC, and it was seen at the time as the greatest challenge to the American constitution since the Southern states attempted to secede from the Union and Abraham Lincoln went to war to prevent them.

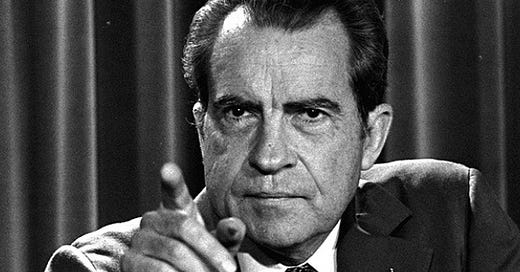

The Saturday Night Massacre, a major turning point of the Watergate scandal, took place on October 20th 1973. While Americans went about their weekend business, while the war in the Middle East rumbled along, a mere 10-days after his Vice-President Spiro Agnew resigned over charges of tax evasion, President Richard M. Nixon, raised the stakes in his fight to keep the truth about his involvement in the original crime and the subsequent cover-up secret.

It's tough to quickly summarize all the events of Watergate from the burglary of the Democratic offices at the Watergate building to the President's resignation. The narrative's main turning points were on legal ideas related to executive power and judicial independence in America's Constitution and the statutes and case law that underpin these ideas. Statutes and case law are couched in specialized language. The political and moral philosophy behind them are easier to follow - and it is from the philosophy that the outrage flows.

First the details, then the outrage

In May of 1973, Archibald Cox, a law professor at Harvard was appointed "special prosecutor" to independently look into the Watergate scandal. The appointment was made by Attorney General Eliot Richardson, himself a Harvard man, who had only just taken up the post, following the resignation—because of Watergate—of Richard Kleindienst, another Harvard law graduate.

The president appoints the attorney general. In America, it's a far more powerful position than in a country such as Britain. The position combines the legal authority of the Home Secretary, Justice Secretary and Director of Public Prosecutions. He or she is then confirmed by the Senate. In his confirmation hearings, Richardson had promised to give the special prosecutor complete independence - including subpoena power - to follow the evidence wherever it lead.

A few months later it lead to the Oval Office when it was revealed—in a Senate hearing on Watergate (so many hearings, so little time to explain each one's legal authority)—that Nixon was recording all conversations there.

Cox issued a subpoena demanding that Nixon turn over the tapes. Claiming executive privilege, Nixon refused and offered a compromise: a Republican Senator would listen to the tapes and provide a summary. Cox turned down the offer and stood by his subpoena power.

That was on a Friday.

Presidents don't need high-priced media advisers to tell them that if they're going to do something unpopular they should do it on the weekend when interest in the news is at a low. Late Saturday afternoon, the President ordered his Attorney General to fire Cox. Richardson refused and resigned. Nixon then ordered Richardson's deputy William Ruckleshaus—you guessed it, another Harvard man—to fire Cox. Ruckleshaus refused and resigned.

The onerous task next fell to the country's solicitor general, Robert Bork—not a Harvard man—who executed the President's order. Cox was fired, his offices sealed, and the FBI sent in to seize papers. All of this took place in the space of a few hours that Saturday evening.

Those are the legal details. Now came the philosophical outrage. Anthony Lewis, New York Times columnist, wrote:

“The General [Alexander Haig, Nixon’s chief of staff] conveyed President Nixon's order to fire Archibald Cox as special Watergate prosecutor. Mr. Ruckleshaus, like Elliot Richardson, refused. Then General Haig said: ‘Your Commander in chief has given you an order.’

“There it was, naked: the belief that the President reigns and rules, that loyalty runs to his person rather than to law and institutions. It is precisely the concept of power against which Americans rebelled in 1776 and that they designed the Constitution to bar forever in this country."

And if you think that overwrought, a more dispassionate observer, Fred Emery, also in The Times wrote:

"Over this extraordinary weekend Washington had the smell of an attempted coup d'etat … Some of the soberest men in government and out are now privately expressing anxiety that the military might now intervene - either to back the President or throw him out."

For the first time since Watergate erupted, a plurality ofAmericans thought Nixon should be impeached.

The calls for impeachment came from legislators as well and not just Democrats, a fair number of Republicans joined in. Not so much because of the legal details of the cover-up but to preserve a basic non-partisan precept of a functioning democracy: the President is not above the law.

Nixon was as good as gone after his Saturday Night Folly. Although it took some time. The law, when every “i” is being dotted and “t” crossed can be a slow-moving machine.

The legal machine moved at its own pace over the next ten months, the tapes would ultimately be produced, step by step, up to the moment when articles of impeachment were drawn up.

Nixon, was like a champion chess player who can see many moves ahead and knows he's in a losing position but still makes his moves in the hopes his opponent might make a mistake. In the end though, Nixon ran out of legal maneuvers and had to resign. But the game was over on the Sunday morning after the Saturday night before in October 1973 .

On the day after Nixon's resignation, an editorial cartoonist - five decades is a long time and I can't remember which one - published a drawing of the Constitution. As in the original manuscript the magnificent opening phrase, We, the People, is written five times as large as the rest of the document. The simple caption read, "It Works!"

So here was victory as it was more thoughtfully expressed. The constitution had withstood the most serious challenge by the nation’s chief executive in its history. It had withstood the stress test. It had checked presidential power.

End of story? For many people who had come of age during Nixon’s presidency it was.

Nixon was gone and it felt so right. For many people like me, whose college years coincided with his presidency, the charge sheet against him stretched to infinity: The man who invaded Cambodia, on whose watch students had been killed at Kent State and Jackson State, the man who ordered the Christmas bombing of Hanoi when peace talks to end the Vietnam war were underway; the anti-communist zealot who destroyed innocent lives for his own political gain, the cynic who extended civil rights protection on one hand but reheated the fire of racial division among the southern working class; the frankly weird guy, who was so darkly obsessed by Harvard—John F. Kennedy's alma mater—a university to which he had no connection, that he surrounded himself with Harvard men, including Henry Kissinger. A man so insecure that he condoned a "dirty tricks" squad that used police state methods to obtain information on his Democratic opponents who in 1972 were no threat to his re-election anyway.

Gone.

We won.

And were overwhelmed by complacency. In the autumn of 1973 public opinion polls had Ronald Reagan, someone even more right wing than Richard Nixon, as front runner for the 1976 Republican presidential nomination.

Reagan as President seemed like a joke, the Republicans were lost to history.

Anyway, there were more important things to worry about than Republicans' self-destructive tendencies. Time was advancing on us - the moment to start making a living in earnest was at hand.

That autumn of 1973, I was making a living but not in earnest. It would be a few more years before I found my way to journalism and work in Washington DC. I arrived in the Capitol a few weeks before Reagan's inauguration.

Over the next few years I lived on and off in D.C. and each day, each interaction, slowly reinforced for me that everything had changed in the Autumn of 1973, but not in the way I thought at the time.

For Republicans there were two conflicting elements at the heart of the Saturday Night Massacre. A confrontation about the extent of the President's, the executive's, privilege to run his office as he sees fit; and the personal antipathy so many felt for Nixon.

The Republican hard-right, not yet in control of the party, never really liked or trusted Nixon. He had run for Congress as one of them, a Red-baiting, reputation smearing, no holds barred campaigner.

His 1950 campaign for the US Senate set a template for electoral success that would metastasize through the entire Republican Party by the time of Donald Trump. His campaign adviser, Murray Chotiner said,

“The purpose of an election is not to defeat your opponent, but to destroy him.”

In this case, Nixon’s opponent was a her: Helen Gahagan Douglas, a former actress, a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt. Everything about her life came under attack including her actor husband Melvyn Douglas, who happened to be Jewish. One Nixon surrogate, Gerald L.K. Smith ,was heard on the radio telling listeners, not to vote for a woman “who sleeps with a Jew.”

Nixon’s telephone bank workers made calls and asked, ““Did you know that Helen Gahagan Douglas is married to a man whose real name is Hesselberg?” Melvyn Douglas was a professional name, Hesselberg was, in fact, his family name.

Douglas lost to Nixon. During the campaign, she prophetically confided to a friend,

“You know, what happens to me personally isn't very important. But that pipsqueak [Nixon] has his eye on the White House and if he ever gets there, God help us all."

It turned out though that Nixon was not as narrowly ideological as the GOP hard-right —self-styled “conservatives”—would have liked. He was too much of an internationalist. He pursued detente with the Soviets, and opened up a relationship with the People’s Republic of China. Conservatives wanted to bomb both countries. There was more on the charge sheet against Nixon. He extended and deepened civil rights legislation. He raised taxes.

But after he was forced to resign the Presidency he became a martyr to the cause of a strong executive, something Republicans are all for when a Republican is President.

At the grassroots the party began to remake itself. “Never Again” seemed to be activists’ primary motivation. Ivy League niceties, East Coast old money, a sense of bi-partisan fairness which had been a part of the Republican party since the Gilded Age, lost what influence it had left.

The party's centre of gravity which had slowly been shifting westward for decades—Nixon was a native Californian, and before him Barry Goldwater was from Arizona—now tipped all the way over. Ronald Reagan, a small-college Midwesterner transplanted to California, defeated Yale educated George H. W. Bush, for the nomination and offered him the consolation prize of the Vice-Presidency.

The party deepened its hold on the South.

These new Republicans were not big on compromise and the wound from one of their party—if not one of their own—having been driven from office is one that has never stopped festering.

Democrat Bill Clinton, had to deal with special prosecutors almost from the beginning of his term and eventually faced an impeachment trial for real. Nixon resigned before he was impeached. Barack Obama’s second term saw his foreign policy choices on Libya lead to endless investigations of his Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton.

Payback.

In other ways, the Saturday Night massacre continued to play out.

Robert Bork, the man who ultimately carried out Nixon's orders that Autumn afternoon, was nominated by Reagan to the Supreme Court. Bork later claimed Nixon had promised to nominate him to the court as the quid pro quo for firing Archibald Cox.

The judge was rejected, in part, because of his willingness to fire Cox.

On the day Bork was nominated, in another part of the Capitol building, hearings on the Iran-Contra affair—arguably a worse demonstration of unchecked executive power than Watergate—were taking place. On the hearings panel, making the argument for unrestrained executive power, was a Republican congressman from Wyoming who had served in the Nixon White House, Dick Cheney.

As George W. Bush's Vice President, Cheney, given a helping hand by al-Qaeda's 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center, took the position to its logical extreme. "When the president does it, that means it's not illegal," Nixon told David Frost at one point in their famous interviews. Cheney brought that philosophy with him to the Bush White House.

So how did this disgraced idea make a comeback? Here's an unprovable theory, at least to professional historians, but it makes sense to me.

Five days after the Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon held a press conference. Deference had long since exited the relationship between the President and the reporters who covered him. Towards the end of the session the following interchange took place.

A reporter asked:

"What is it about the television coverage of you in these past weeks and months that has so aroused your anger?"

"Don't get the impression that you arouse my anger.

“I have that impression.”

“You see, one can only be angry with those he respects."

Nixon came back to the theme a few minutes later.

"When a commentator takes a bit of news and then with knowledge of what the facts are distorts it viciously, I have no respect for that individual."

A four decade war on the press's legitimacy had begun. The idea took root among the Republican grassroots that it was a biased liberal press that made the molehill of Watergate into a mountain of constitutional crisis.

Legislation was enacted under Ronald Reagan that removed the so-called “Fairness Doctrine”, the legal obligation for broadcasters to air both sides of controversial issues. This led to an explosion of opinionated propagandists on the air waves relentlessly attacking those very same institutions Nixon had no respect for: the mainstream media. It continues to this day, degrading American public discourse. It has fed into the hyper-partisan political culture that has made the US practically ungovernable.

Forty years later, only one of the principals of that evening was still alive, William Ruckleshaus. He was running a foundation in Seattle and still active in national life. For a piece I was doing for BBC Radio, I wrote to him and asked, “If you knew that ultimately the President would be forced to resign and that future generations of Republican legislators would spend so much time trying to even the score, would you have taken a long view and done what was necessary to protect the president and keep him in office?”

I didn't really expect an answer but within two days an e-mail came back:

In October 1973, many across the political spectrum agreed with Mr. Ruckelshaus. But the change that Ruckelshaus thought his action might bring was not the change that came to Washington. And those who thought they were the victors then could not have begun to imagine where American politics would end up.

(Read on to Chapter Ten)

And if you need to catch up on earlier chapters, Part 1 of the book , Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here:

NOTES:

https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/books/first/m/mitchell-tricky.html

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-04-09-me-664-story.html