CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: 1995, GOING SOUTH TO PHILADELPHIA, MISSISSIPPI

Part IV: 1990s America, Road Trips in Flyover Country

In the autumn of 1995, precisely ten years after leaving New York for London, I traveled around Mississippi on assignment for the BBC World Service. This chapter is based on the five essays I wrote for World Service immediately following that trip. They are edited only for tense where appropriate. These words are the contemporaneous record of what I saw and heard on that mid-90s trip with no retrospective judgment from the present.

Sometimes, if you're lucky, you get a chance to confront your fears. Fear was on my mind when I chose to travel through Mississippi. I've travelled through most of the United States, but I had always avoided the place. When I announced to friends up North that I was heading for Mississippi they laughed and asked “Why?”, then told me to be careful. My fear of Mississippi arose from a single incident.

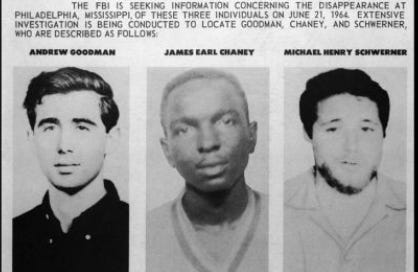

In June 1964, three civil rights workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner were killed near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Goodman and Schwerner were Northerners, from a background very similar to my own: white, middle-class, liberal and Jewish. The fact that I lived at the time in the more famous Philadelphia—the one in Pennsylvania, where the Declaration of Independence was signed—added a heavy dollop of irony that made the murders stick inside my skull.

In my memory, the deaths of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner are of equal importance to the other political murders of the time: John F. Kennedy, Robert Kennedy, Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers and Malcolm X. They are an event to be remembered and examined when, sitting in my home in a foreign country, I think about what it means to be an American.

Most of you who have found your way to this work in progress will know the back story, if not from being alive at the time then from seeing Alan Parker’s film Mississippi Burning, but if you don’t know it, here it is:

June 1964, what would come to be known as the Freedom Summer. 100 years after Lincoln freed America's Black slaves, President Lyndon Johnson has sent to Congress detailed legislation to guarantee their descendants basic civil rights, including the right to vote.

While Congress prepared to pass the legislation into law, several thousand college students from outside the region travelled South and joined with the four major civil rights organizations including NAACP, CORE and SNCC to help Blacks register to vote.

It was a terrifying and heroic time. Black churches, assembly places for that community, were fire-bombed. The kids from outside the region were constantly harassed and threatened with physical violence. They couldn't turn to law enforcement agencies for protection because frequently it was the local police doing the harassing and the threatening.

On June 19th 1964, the US Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. On June 21st, James Chaney, a Mississippi-born African-American organiser in Philadelphia, and two of the students from up North, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, disappeared. 6 weeks later, their bodies were found buried in an earthen dam a few miles outside of town. All three were in their early twenties.

I was old enough to understand that any place where you could be murdered for helping people to vote was a fearful place.

So, three decades later, on the kind of sunny cloudless day where you can see with absolute clarity into the deepest part of the sky, I found myself driving in a moderate state of anxiety into Philadelphia, to get to the heart of my fear.

I doubt if the few blocks that make up the downtown had changed much since the night the three civil rights workers disappeared. Philadelphia is an old-style, Southern town. Several thousand people live there. Main Street is lined with one and two storey brick buildings. Downtown is dominated by the Neshoba county courthouse, set back from the main road in a raised lawn. Further down the street there's an old cafe called Dot's, which functions as a town assembly hall.

Dot’s was a film set designer’s idea of a small Southern cafe, worn around the edges by real life and the smell of fried grease and tobacco. I stopped in for coffee, drank several cups because it was weak, all the while trying to figure out how to work my way into a conversation but I couldn’t get past the fact that Dot’s clientele looked like an extra’s casting call for Klan members in Mississippi Burning.

I clearly had not yet conquered my nervousness about being in this town.

Walked over to the library and asked to see the old files about the incident. The librarian wearily told her assistant where to find them. When I tried to start a conversation with her, she turned brusquely away. Stopped in at the Neshoba Democrat, the town's weekly newspaper, but the tiny staff had been up late covering the election I had heard so much about in Tupelo, and had the day off.

I walked into the high school, curious to see how the incident was taught. A history teacher gave me a textbook to look through. It was all there—a fair and honest account—but she too declined my request to meet and talk about the murders.

Restless, need to talk, can’t find anyone, anxious, just move on down the line, be patient.

Go to court house watch the wretched of the earth being arraigned. Beltless, no shoelaces lest they try to hang themselves, a procession of youngish men, Black and White, are brought before the court for a brief appearance and to be taken back to the cells when bail is set at a level they have no hope of making.

Just across the street from the the courthouse is a Christian book shop. Go in, browse. Pick up a book that gives advice on how to protect your faith when you go to college. There wasn’t just one book on the subject. Clearly universities are places where a Christian youth can expect to be confronted by secularists who deny the story of creation as well as experience daily challenges to chastity inherent in the humanist lifestyle.

Still agitated and having yet to speak to anyone in a meaningful way, I drove around the edge of the town, still vacillating over whether to stay or go, leaning very much to the latter.

I'd paid my respects to the memory of the dead, and no one in town wanted to talk to me, although the truth was I really didn’t want to talk to any of the locals. The apprehension that had accompanied me from Tupelo was pushing me to leave and since the afternoon was fading, I decided to move on. But about 2 miles out of town, I came over a little rise and saw an extraordinary sight which made me reconsider my plans.

The woods suddenly opened out, and there was a huge parking lot and buildings covering an area about the same size as downtown Philadelphia. Dominating the complex was a massive neon sign, coloured with strips of carnation and arcs of blue and green and the word "Silver Star" in white, then purple, then pointillist flashing bulbs. It was a gambling casino; a little bit of Las Vegas in the middle of the woods. I pulled into the parking lot and walked around, slightly amazed. A middle-aged black woman was walking towards her car. There was no problem starting a conversation here.

"You win all that money?" she asked.

"I haven't even started yet. Did you win?"

"I lost $80. That's all I had."

"Better luck next time."

"My son gonna kill me. He gave me that money for the phone bill."

She was not alone. Hundreds of thousands of people were losing money at casinos around Mississippi in the four years since gambling had been legalized. The numbers were extraordinary. In that short time 28 casinos had opened around the state. The year before my trip they had taken in almost $29 billion. Let me allow you a moment to consider those numbers: 28 casinos, 29 billion dollars.

Not everyone was happy about this. Christian fundamentalists, who provided so much support for the state's ruling Republican party, were in despair over legalised gambling, and the state's liberals were in despair because the casinos encourage poor people, like the woman I was speaking with, to gamble money they can't afford to lose. But on the other hand, the state gets a lot of tax money—the roads I'd been driving on were awfully well-paved—and casinos mean jobs. 1700 people work at the Silver Star, which is open 24 hours a day, 365 days of the year. Gambling has given Mississippi, by far the poorest of the 50 states, a glimpse of a more prosperous future.

The Silver Star is slightly different than the other casinos because it's on land. All the others by law have to be on or next to water. The Silver Star avoids this because it's on the Choctaw Indian reservation and is subject to different rules. I decided to change my travel plans and try my luck at the Silver Star that night.

Walking into the casino was like stepping across the playing surface of a giant pinball machine. You step down from the main entrance into rows of slot machines, 1800 in all, and make your way towards crap tables. In the middle of the vast room is a bar and a bandstand, on the far side there are more slots and blackjack tables, and in the back is a separate room for poker. At 7 o'clock on this Wednesday night in November, the room was far from full, but there had to be at least a thousand people on the floor, mostly playing the slot machines.

People were perched on stools with buckets of coins and tokens feeding the machine. The more serious players were literally plugged in. They wore a purple flex cord around their necks, at the end of which was a credit card with a certain number of plays electronically encoded on it. They inserted the card into the machine and without shifting position, played the slot like a piano, simply moving their hands across the buttons.

It was the most integrated place I had been to so far in Mississippi. Blacks and whites mingled freely. Losing money is an equal opportunity pastime. Most folks playing the slots were poor, the crap and blackjack tables had a more affluent clientele. They were much more raucous than the folks buried in the furrows of slots, plugged in, staring at their machines with the grim seriousness of assembly-line workers trying to earn a living from repetitive labour they detest.

I wandered around trying to pluck up the courage to play. I watched people winning thousands of dollars and saw people losing large amounts too. After several hours I set myself a limit on what I could afford to lose, and sat down at a blackjack table. Within ten minutes I had lost it. Just another 20 bucks, I said to myself. 3 hands later, it was gone. In 15 brutal minutes, I had blown 60 bucks. I went to the motel and went to sleep.

Still brooding about it the next morning, I went into Philadelphia to have breakfast at Dot's cafe. The subject that morning among the regulars was the casino—what else?—and the waitress was having a gossip with a girlfriend who claimed to be doing rather well at the Silver Star.

“Won $400 last night at the slots. You should try it," she told the waitress.

"Scared money don't win, and honey, my money is terrified." the waitress replied. "Do you know how much I can buy for $20 down at the junk store?"

"You know how much you can buy with $400?"

I eavesdropped, nursed cups of coffee and time-travelled a bit. Dot's is the kind of place where the decor is only changed when it wears out, and since the pace of life in Mississippi runs at half the speed it does in most parts of America, it hadn't changed in decades. It was easy to sit at the lunch counter, being served with great charm and courtesy by the waitress while being ignored by everybody else, and imagine it was the Freedom Summer, and that the reason you were being ignored was that you were a Jewish Yankee liberal in town to cause trouble. But from the conversation I was eavesdropping on, it was clear I was the only person in there thinking about 1964. I forgot about the hole in my pocket where the $60 used to be, and went up the street to the offices of the Neshoba Democrat, to resume my inquest into Philadelphia's past.

The editor, Stan Deerman, was in. He had lived through those times. Deerman, soft-featured in his late 50s, spoke quietly about the summer of 1964.

"There isn't a day that goes by that I don't think about what happened here," he confessed.

The murders were the reason he lived in the town. As a young reporter at another paper in the South he had been assigned to cover the events and then the subsequent trial in 1967 of 18 people on charges of conspiracy—not murder. Only seven were convicted and they were given slap on the wrist sentences.

Stan Deerman took a job with the Nehsoba Democrat and never left. He was still trying to make sense of the murders. For him, the enduring question was why it happened in this particular town. Not every white person in Philadelphia was a member of the Ku Klux Klan. The town even has a progressive streak in it. The Democrats' unsuccessful candidate for state governor in the recent elections came from one of Philadelphia's prominent families. As for others in Philadelphia, Deerman felt that most people in the town didn't think about it much. There were other things on their minds. Philadelphia's economic base was being completely changed by the casino's success. New hotels were going up, and shopping malls. The sleepy town was becoming a regional economic centre.

While we were talking we heard someone in the newsroom asking for Stan. It was Milton Moore, a local leader of the NAACP. Stan brought him into the office and introduced us. Milton Moore was an interesting fellow. He had grown up in Hopewell, a black hamlet a few miles from Philadelphia. In the 1940s as a teenager he left the area.

"I was a free slave, that’s what I called myself. I had no choice but to pick cotton and live within the rules of this society," he said.

He spoke with tremendous energy. No one I met in Mississippi spoke as fast. Milton Moore joined the US Army in the late 1940s, although that didn't get him away from race laws, the US army was still segregated then. He had risen through the ranks and become a Sergeant in a tank unit. What he remembered about the summer of 1964 was this: he was deployed in Germany and watching pictures on television of churches being burnt back home in Mississippi, and stories about the disappearance of Goodman, Schwerner, and Chaney, and trying to be in contact with his family to make sure they were alright, and the Red Cross calling him, to assure him that yes, they were. And thinking to himself,

“Here I am in Germany, we're facing the Russians across the border, and they really need my tanks on the streets of Philadelphia Mississippi.”

Milton left the army after 2 decades and became a policeman in Washington DC. When he reached retirement age, he drove out of DC and never looked back. He drove all the way back home to Philadelphia. The immediate question was why? Why come back to a place where you were a free slave? Well, partially because his family had property out in Hopewell and something else:

"The need was here.”

The “need” was for leadership in the black community.

It was almost 50 years since he left Philadelphia. Did he think things had changed much?

"We're progressing, but it's going slow." Then he confessed, "My people don't want leadership. They're divided among themselves."

The most dismaying thing to Moore was that they didn't vote.

"They just don't seem to care,"

Moore’s voice was perfectly balanced between matter-of-fact and despair.

I wanted to ask him more about the “not caring”. Surely local folks knew this town, this county, had paid a heavier price in blood for Black people’s right to vote than any other place in modern America and that should be motivation for all eternity. But the question never got asked because he was in a hurry to go and his will was stronger than mine.

On my way out of Philadelphia, I drove past the Silver Star one more time. I thought for a split second about going back in to win my money back, then thought better of it. Scared money don't win, and my money was terrified.

Zipping by the casino I was aware that my other fears about the town had disappeared. It’s a new era and Stan Deerman was still there to remember what happened and feel the fear of that Freedom Summer on behalf of everyone. I didn’t have to do it.

In fact I felt so fearless that just past the casino, I saw a scrawny white guy, greasy hair pulled back in a ponytail, looking a couple of days past his last shower, hitchhiking. I stopped and gave him a lift. But that's another story.

This has been the third chapter of Part Four of History of a Calamity, the story of how America went from Victory in World War 2 to Donald Trump and Cold Civil War in a single lifetime … Mine, and possibly yours. The next chapter continues the journey around Mississippi in 1995, going from Biloxi to Natchez and back to Clarksdale. Here’s a preview:

The Natchez camp of the Sons of Confederate Veterans was holding a dinner meeting, the head table was on a little dais. At one end was the American flag and at the other was the Confederate flag. About 25 or 30 people were there. The meeting started with the pledge of allegiance to the American flag.

The assembly then turned to the Confederate flag, and right hands open, palm up, pledged this oath.

“I salute the Confederate flag with affection, reverence, and undying devotion to the cause for which it stands.”

And if you need to catch up on previous parts of my book, Part One, Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here:

Another beaut Michael. I never forget that Reagan gave a "State's Rights" speech in Philadelphia, Mississippi. A fairly loud dog-whistle even then.