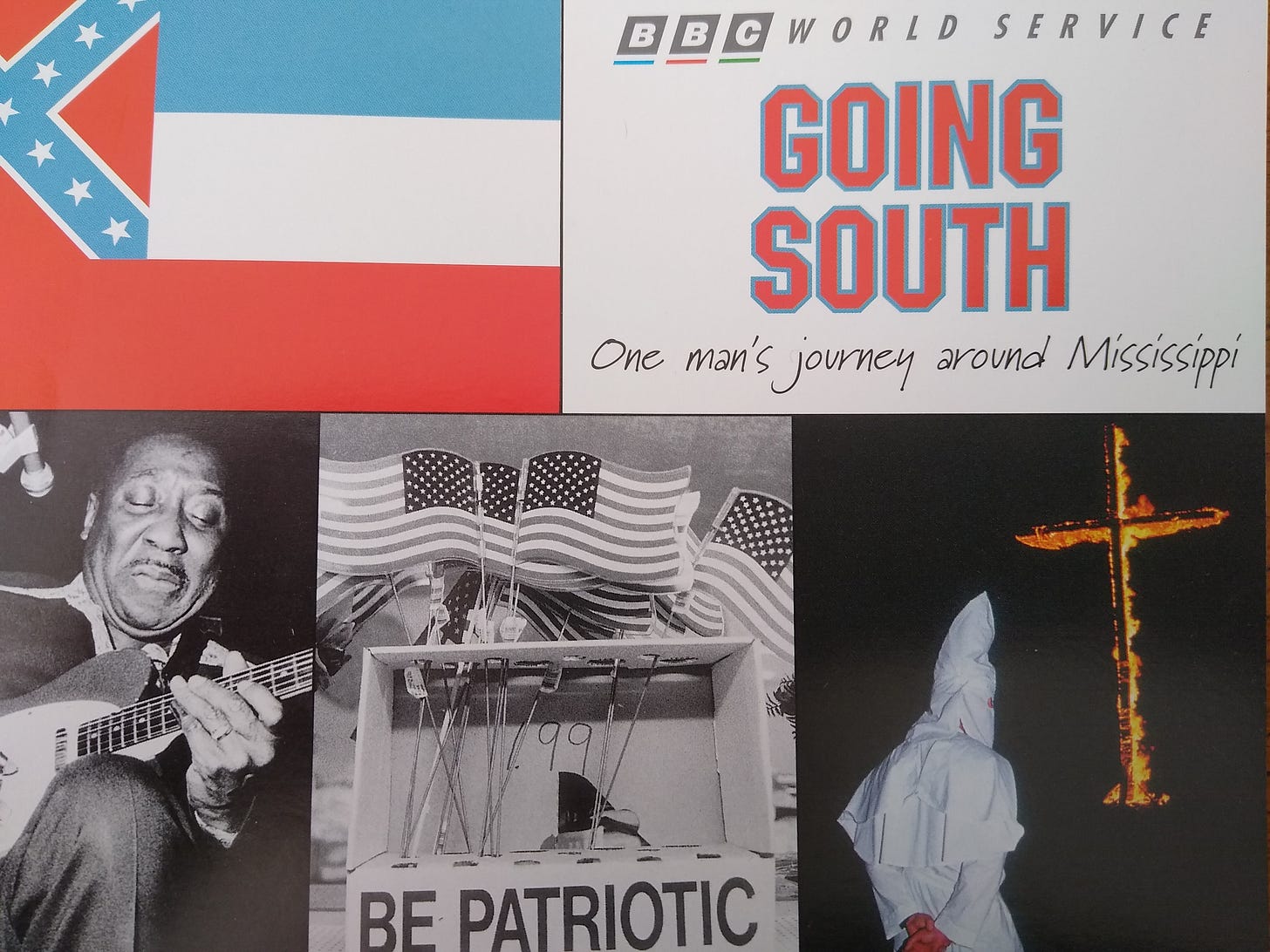

Throughout the 1990s the BBC World Service sent me back to parts of America that were rarely reported on to write a series of essays, similar to Alistair Cooke’s Letters from America. In the autumn of 1995, precisely ten years after leaving New York for London, I traveled around Mississippi. This chapter and the one that will follow is based on the five essays I wrote for the World Service immediately following that trip. They are edited only for tense where appropriate. These words are the contemporaneous record of what I saw and heard on that mid-90s trip with no retrospective judgment from the present.

CLARKSDALE

An ocean and a decade are a good distance from which to observe your homeland. What seems like an earthquake up close hardly makes a ripple over the water, and you see with greater clarity the social changes which have occurred. In the ten years I’d been away the most subtle of these seemed to be America is acquiring a past.

America has always been focused on the future. This is the reason for American optimism. My compatriots took comfort in the certainty that tomorrow would always be better than today. With the constant looking ahead, the past tended to be ignored, but in recent years, the future has become a doubtful place. People have begun to look to the past for certainty. But they're having a hard time finding it. The problem is that while the facts of American history are generally agreed, what those facts mean isn't.

There's one region of the country where this grand generalisation isn't applicable: the South. Perhaps because it was briefly a nation of its own before being forced to rejoin the United States after a bloody civil war, but in the Southern states people know exactly what the facts of their history mean and they see in that history signs pointing a new way forward for the whole country. It's no surprise that the most radical politician in the US, Newt Gingrich, Speaker of the House of Representatives, is a history professor from the South.

The sovereign state of Mississippi is the most spiritually Southern state of all. It's the Southern state where the past has its tightest grip, or, so it had always seemed to me even though I'd never actually been there. So I convinced the BBC to let me drive around the state and investigate the place where “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

As I headed South out of Memphis, driving by Elvis Presley’s home, Graceland, into Mississippi, the opening line from an old Blues song by Willie Brown kept going around over and over in my head, “Can't tell my future, sure can't tell my past”. It was one of the first country blues tunes I ever heard. The song had been recorded in the 1920s, in an area of northwestern Mississippi called the Delta and that's where I was headed.

As a Northerner, a Yankee, I had plenty of preconceptions about Mississippi, most of them negative. It had never been a place that enticed me, except for the Delta, where the Blues was born. The Delta seemed like a good place to acclimatise myself to the state. I'd listen to the Blues in its purest form and ease myself into this trip. But with each mile I drove into the region, it became clear there would be no time to adjust my Yankee sensibility to this very different world, because I was in the poorest, saddest looking part of America I had ever seen.

I passed through tiny hamlets, each one more forlorn then the last. The one-storey buildings were a strong breeze away from collapse. It was impossible to believe that the stores and houses had ever been new or that they were in the United States.

I rolled towards Clarksdale, the Delta's unofficial capital. On the outskirts of town, on Highway 61, there was a neon strip of fast food joints, motels and filling stations. These ugly buildings came as a relief, they were the first new ones I had seen in several hours. Turning where a small sign pointed towards downtown, I re-entered the landscape of poverty. Blocks and blocks of it. I looked for the main drag and turned down Issaquena Street. It had been a business district … once. Now it was a forbidding stretch of one and two storey buildings on the verge of collapse, with dozens of people wandering from door to door. They were all Black. Just as every person I'd seen walking in the little tumbledown hamlets was Black. In fact other than a few guys fishing by a dam across a small creek, I hadn't seen a White person in the street since I drove into the Delta.

I went under a railway bridge to the right side—the white side—of the tracks and found myself in downtown Clarksdale. I wandered around for a bit and stopped by an odd-looking building, shaped a bit like a Mississippi riverboat. which turned out to be a Blues record shop, Stackhouse Records. I walked in and started thumbing through the racks. Seated behind the counter was a woman in her early 20s, sitting crosslegged on a chair, wearing a long smock which draped over her round belly. She was heavily pregnant.

We started talking about records and then she asked where I was from. People from Mississippi have a distinctive accent. I didn't have it and neither did she, so as a couple of outsiders we began to talk. I explained what I was doing, travelling for the BBC and reporting on the people I meet. She asked my impressions so far, and I said that in the 5 or 6 hours since I had been in Mississippi, my first impression was of the poverty. I had never seen anything like it. It looked more like photos of Soweto in South Africa during the worst days of apartheid.

Then she asked me "Have you noticed how black people are here?" I was surprised by the bluntness with which she asked the question and took it as an invitation to answer back in an equally blunt way. "I'm glad you asked that. Because the folks here are the most African looking African Americans I have ever seen.”

Now, whatever embarrassment I might have felt about discussing race this openly— and as a liberal from the north I felt plenty—it was eased by the fact that the young woman, whose name was Selena, was herself of mixed race. Her father was black. Selena picked up my point about people's complexions. "That's right. They say the separation of the races here in Mississippi was much stronger than in other parts of the South, so there wasn't the same race mixing that happened on plantations in other places."

Selena, whose own complexion was very light brown, went on to tell me that local black women asked her why she hung around when, with skin so light she could pass for white, she could get out.

The young woman however was staying for a while because at the weekend she was marrying the father of her baby, a fellow named Jim O’Neal, who happened to own the shop and a blues record label, Rooster Records, and she invited me to come to the wedding.

I spent the next few days exploring the Delta around Clarksdale and spent hours driving fast up and down Mississippi Highway 1. There was a memorial plaque noting Nathan Bedford Forrest, a founder of the Ku Kux Klan, had had a plantation nearby. Not far away from that sign was a cotton gin. The year’s cotton crop had just been picked and the Delta’s fields were various shades and shapes of brown but the parking lot of the gin was full of trucks with bales of dirty white cotton bolls waiting to be processed through the infernal machine.

The giant apparatus occupied a big, corrugated metal factory shed and rattled like a snare drum trapped inside a kettle drum rolling over and over as if it had fallen out of the back of a truck. Worker safety signs were plastered all over the factory with life-size plastic hands covered in blood. The cotton gins are built around rotating saws which separate the seed from the cotton fibre in the bolls and one of the jobs was to pick the racks clear of any debris left over. Apparently severed hands were a common work injury.

Paid homage to Tennessee Williams, who grew up in Clarksdale, by driving out to Moon Lake where there is a plaque marking the spot of the Moon Lake Casino. In A Streetcar Named Desire, Blanche Du Bois dances the Varsouviana in the Casino with her young husband, then tells him he disgusts her because she has seen him in bed with a man. Her husband then goes outside and shoots himself. That incident is the wound in Blanche’s soul that never heals.

I began to notice there were white people, you just had to know where to find them. I spotted them in their cars or out at the new shopping mall on Highway 61. But I was becoming increasingly disturbed by the fact that white folks seemed so separate. I stopped in at the Clarksdale Press Register, the local newspaper, and one of the editors, Debbie Long, Delta born and bred, tried to explain why.

"The biggest change in my lifetime without a doubt has been integration" she began. Long was in school in the mid 1960s when forced integration programmes had gone into effect. Most whites simply pulled their children out of the state system and sent them to private academies, rather than have them attend school with black kids. Debbie Long's parents hadn't, and overnight she found herself one of only 2 whites in her class. She did not have happy memories of her minority status. I asked her about the absence of whites in the street. "In the Delta," she explained, echoing Selena, "The races don't mingle in any social sense." Work is a different question. Debbie's family were farmers and their hired hands were black. Her Daddy provided their housing. Individual relationships were formed, but they were limited.

"Down here we have a saying about Blacks. Love the individual, hate the race."

There must have been a moment's silence, then I said, yet again,

"You all do speak frankly about race down here."

As Debbie Long showed me to the door, she asked me to try and understand Mississippi, and to be kind in what I wrote.

I needed to get away from all this race talk. I drove out of Clarksdale. Back towards Hwy 1. Due west on the horizon was a hump running as far as the eye could see. It was the levee, the earthwork built up to contain the Mississippi river within its course.

Near Rosedale, I drove up over the levee and a few hundred yards on the other side was the massive, mile-wide river, turbid with silt carried from places 1000 miles away. From Minnesota and Dakota and Ohio.

I spent more than a little time watching the river flow, but I couldn't get the race issue out of my mind. I knew 'd have to deal with it when I came to Mississippi but I'd had no idea it'd be like this. Frank talk about race. All euphemism stripped away.

To say, The question of race is the central question of American history is too euphemistic.

The question of black people and their role in society is the central issue of American history, and the inadequate resolution of that issue is behind a tremendous amount of social tension around the country today. Uh-uh. That is too euphemistic.

The hostility between whites and blacks is greater than at any time in living memory. No-one knows what the other side wants, people hardly have words to talk to each other. Integration was the answer when I was growing up, now plenty of people on both sides question it.

But it seemed in the Delta all questions about race were resolved long ago. Integration may be the temporal law, but segregation is the spiritual law. Segregation is the answer. And blacks in the Delta seemed on the surface to accept that, even if their separateness condemned most of them to living in poverty which, until I saw it with my own eyes, was something I could not credit existed in America.

And it just didn't seem right.

As you can tell, I was a little upset and confused. Wanting to have some frank talk about race with some local black people, I went back to Issaquena Avenue that evening.

I followed a crowd into a club, the one juke joint in town that seemed open this night. It was as decrepit inside as it was outside. I was the only white person in there. No-one made much of the fact. I sat down at a table and two young women joined me, but serious conversation was not on their mind. Fun was. They started talking themselves into a good time, and the music hadn't even started. The younger of the two, about 18, told her friend a joke. I laughed too, she turned to me and said "I've got two kids. I told my babies, 'I work for you all week. Tonight is my night.'" Then she smiled. She was missing her front teeth.

The band struck up and promptly blew out all the fuses plunging the room into darkness. Even the electrical system in this juke joint was decrepit. It took 2 more tries before they finally got going, but when they did, the sound of their Blues spread thick and sweet in the ear the way honey spreads thick and sweet over the tongue.

The rhythm of the music made it impossible to sit still. I simply stood up out of my chair and started dancing by myself. The physical decrepitude of the place seemed unimportant. The questions I wanted answered seemed unimportant too. It was just the music.

Finally, Saturday night came. Selena's wedding. For the first time in Mississippi I was in a room with white and black people together. Selena's fiancé, Jim O'Neal, had come to the Delta 20 years before, stayed, and started recording the local musicians. Most of them were at the wedding. The white folks were a handful of locals for whom the music was a bridge across the chasm between their own upbringing and their Black neighbours. There were also a few Yankee liberals who had made a permanent home in the Delta, hooked on the culture.

The ceremony was being held at Mayfields, a big house on the white side of the tracks with a huge wraparound porch, large entrance hall, and parlours and living rooms going off in all directions. A piano was set up in the entrance hall and a young black man was playing softly. If the wedding had been held in church, he'd have been playing a selection of hymns and popular classical airs on the organ. Here, it was blues, but he imparted to the notes the sacred feeling of church music. The ceremony was improvised and beautiful, and when it was over the pianist stuck up Let the Good Times Roll. And they did. We adjourned to the Rivermount Lounge, another tumbledown juke joint, for a real party.

The party started with a fife and drum band playing a music that went back to slave times and is a rhythmic keening precursor to the blues.

While the band plugged in, people went up to the bar and bought soft drinks to use as set-ups. This juke joint had no liquor license so people had to bring their own bottles of whiskey and buy coke or ginger ale to mix in it. I found a table and plunked a bottle of Old Forester down and started to make friends.

The party gathered pace quickly. Everyone who could play the blues did and everyone who couldn't, danced. Out on the dancefloor we were all one ensemble. There was no bandstand, the musicians mingled with the dancers. But I'd be lying if I said the full distance between the white folks and the black folks was bridged. It wasn't.

A Black woman about my age was sitting at my table and I asked her to dance and we did for a bit but not enough to break any social ice. A very pretty young woman in her twenties was sitting on her own. Seemed a shame. Someone nodded at her and said that’s Charlie Patton’s granddaughter. Charlie Patton is one of several fathers of the Delta blues. His face was a familiar one to college blues freaks from a popular poster of his image which hung on many dorm walls in the lat 1960s and the young woman did look very much like him, her features more Native American than African-American. Although doing the math it was more likely she was his great grand-daughter.

I asked her to dance and she brusquely refused.

The drinking and dancing went on for hours and how the night ended I cannot remember, but I am still here to tell the tale. Let’s leave it at that that.

I had one more musical appointment to keep before leaving the Delta. I had struck up conversation with Kenneth Lackey, the young man playing piano at Selena and Jim's wedding. He seemed interested in answering my questions about being black in this segregated world. Lackey invited me to a concert of gospel music in which he was singing. He said we might have a chance to chat then. So I packed up and Sunday evening drove over to a church in Jonestown, one of the tumbledown black hamlets I had passed through on my way into Clarksdale.

Add the sacred to the Blues and gospel music is what you get.

There were several hundred people at the concert. Once again, I was the only white person in the room. Lackey came in, and looked surprised to see me. We spoke briefly but it was clear he didn't have time to discuss big questions, he had to make music. I found a seat against the wall in the very last row of the church and once again was left alone to clap my hands in time, or try to, and attempt to reconcile my Yankee preconceptions with the unexpected reality of Mississippi. Once again the music urged me to ignore it.

Beverley Trice and the New Life Singers the headline act were onstage. They were singing a song whose refrain was a simple seven word sentence: 'you don't know how blessed you are'. They kept repeating the phrase but each time it was sung, it seemed to have a different meaning. A statement of fact, a statement of consolation. A benediction.

The spirit moved Beverly Trice. She came off the little stage and began to dance her way up the aisle. Her backup singers laid hands on her to try and control her shaking. As she worked her way through the audience she sometimes reached out to touch someone and chanted the phrase “you don't know how blessed you are.” Over and over she sang, each time emphasising different words, creating a syncopated beat that took me far away from this world.

You ... don't know ... how blessed ... you are.

Youdon'tknow … how … blessedyouare.

Youdon'tknow … how … blessed … you … are.

TUPELO

It was raining. Election day was approaching and I was looking for the centre of Tupelo Mississippi. The rain would stop, the election would be held, but I never did find the centre of Tupelo. The city is going through an economic boom. As I drove in from the West, the rain being flick-flicked from my windshield, I could see a typical city plan of late 20th century America. A gridwork of main boulevards, 5 and 6 lanes wide, along which were strewn shopping malls, car dealerships and little business parks. In this new world of malls and highways, pedestrians had vanished. A new arrival couldn't form a first impression of the local people unless he risked a traffic accident by staring into somebody else's car for a long look at another human being.

Arriving in the rain to a place with no centre posed a problem. My plan was: get to town, find the local hangout for politicians, lawyers and journalists—probably a cafe or diner near city hall or th ecourthouse, a place with strong coffee, good fried chicken and a sassy waitress—then eavesdrop until it was appropriate to join in a conversation, and thus work my way into the community. It's very difficult to sit in a McDonalds or a Dunkin' Donuts drinking coffee and pick up that kind of conversation. Sadly, the chance meeting, the staple of travel writing, was not on the cards.

I checked into a motel, looked through the phone book for the local number for the Republican party office and arranged the contact I wanted to make. I'd come to Tupelo to talk politics, and specifically to talk about the two driving trends of modern American political life: the conversion of the South from rock solid Democratic Party territory to a Republican-supporting region, and the growth of Christian fundamentalist influence in that party. Mississippi was a good place to do that. It had been among the first of the Southern states to veer towards the GOP and, in the last decade, much of that party's grassroots organisation had been provided by fundamentalist Christian groups, many of them from the Tupelo area.

The next day was election day. Mississippians would be voting for Governor. The incumbent was a Republican named Kirk Fordice. When first elected in 1991, Fordice was the first man from his party to hold the Governorship in 100 years and he had created a national controversy when he claimed during the campaign that America was a "Christian nation".

So it was arranged that I would meet retired businessman Glen "Cotton" McCullough, Republican Party activist and financial contributor who kindly took me to a shopping mall for coffee at an Applebee’s. The coffee was weak, it was too early for fried chicken, the only thing Southern about it was the waitress: central-casting sassy and she seemed to know Cotton very well, if the banter was anything to go by. We were joined by Jake Mills, another big Republican supporter, and we started to talk politics.

At one level, the fact that Cotton and Jake were Republicans didn't surprise me—they were wealthy business men—but until recently, Mississippi men of means would have been Democrats because there was no Republican Party to speak of in the region. The Republican Party had been anathema in the South since the Civil War. The reason is simple: it was Abraham Lincoln's party. Republicans in Washington had passed the laws for rebuilding the South after the Union's forces had defeated the southern Confederates. For a century in Presidential and Congressional elections, the South had taken its revenge by voting for the Democrats. That began to change in the 1960s.

Political scientists have published vast treatises on this great shift from the party identified with the common man, the Democrats, to the party of big business, the Republicans. But nursing his cup of coffee, Cotton McCullough had a more succinct explanation:

"The Democratic Party stopped being the white man's party."

There was regret in his voice. Cotton was white-haired, somewhere in his 60s, with a weathered, ruddy complexion and thick gnarled hands hinting at spending part of his life farming. He had been brought up in the Democratic Party but from the mid 1960s on had drifted away. That's when President Lyndon Johnson pushed through his revolutionary programme of social legislation: affirmative action programs to address centuries of discrimination in the job market, and the Voting Rights Act, which guaranteed blacks the opportunity to vote. Mississippi's record on voting was abysmal. It was so bad that federal election monitors are still being sent to the state in 1995 for each election to make sure Blacks are able to exercise their right to vote.

To Cotton and Jake, this was well nigh intolerable. Leaving aside for a minute whether they felt that blacks as a group were capable of voting without the inducement of a few dollars to go to the polling station, something they claimed, for them it was as if the federal government was invading the sovereign state of Mississippi to impose its will. And of course, it wasn't the first time that had happened. "I believe in states' rights," Cotton said. “States' rights” had been the rallying cry of the old South in the years before the Civil War.

From the time America was founded by 13 newly independent colonies strewn across a vast geographical area, there was tension between those who thought that the best way to run the country was with a centralised federal government, or as a loose confederation, with each individual state having a greater responsibility for its internal affairs. States' rights vs the federal government. In Cotton's view, states' rights was the issue that led to the Civil War, not slavery.

I pointed out to my companions it seemed that back then at least, states' rights was a cover for maintaining the institution of slavery. Cotton and Jake shook their heads at my Yankee ignorance.

"Look, the institution of slavery would have died out anyway," Cotton said. Besides, did I know there had been black slave-owners? “There were at least 6 of them over in Natchez. Most whites in Mississippi didn't even own slaves. And now, sending in these monitors, it's like we're being occupied by our own government.” And, McCullough wanted to know, “By what right?”

Mississippi men fought bravely in the federal government's wars. More Mississippians had won the Medal of Honor, America's highest military decoration, than from any other state, or so he claimed. The implication was their blood sacrifice should be enough to keep the Feds out of his state’s business.

The talk was contemporary, but it resonated with disputed history. Draw a radius of 50 miles from where we were sitting and go back 130 years, and the area around Tupelo was a hive of military action. Listening to the two men talk, it was as if the Civil War had ended 30 years ago, rather than a century before that.

There was something familiar in Cotton McCullough's combined sense of aggrievement and certainty, but I couldn't quite put my finger on it until he started talking about his family roots, which were Scots-Irish Presbyterian. The same Protestant stock that had been settled in what is today Northern Ireland back in the 17th century, and that's when the penny dropped. Northern Ireland was my beat for NPR and I encountered the same attitude among Ulster Protestants when they were speaking about Catholics, civil rights, and the blood sacrifice of their boys in the British army at World War 1’s Battle of the Somme.

Aggrievement and certainty, good manners and intolerance. It seems that one's cultural worldview emanates from deep within the currents of one’s family's history. A century and more and transplanted thousands of miles away, the Ulster Protestant’s essential world view remains the same, only focused on African Americans instead of Catholics.

They were Republicans and unabashed racists, I wondered whether the two men could support General Colin Powell if he became the Republican Party's nominee for President. The retired General's possible bid for the nomination was the hot topic around the country this November day. "No," they said. Because he was black, I asked? "No." Powell was not strong on family values, and he supported affirmative action. Their view? The Powell candidacy was being created by the liberal media in Washington, desperately frightened that a real conservative Republican would get the party's nomination.

Much coffee had been drunk. Jake Mills had business to attend to and left, Cotton kindly offered to take me to a last-minute election get-together out in the country, in a hamlet called Auburn, that evening. There I met Devin Dutka. His business card said he was “Evangelist of the Crossroads Christian Church” and he invited me to his place the next day for lunch.

His home was in a scattering of live-in trailers and small-frame houses. Pastor Dutka lived in one of the latter. In the drizzly grey daylight you could see Auburn really wasn't the country any more. The malls and new developments of modern Tupelo were approaching rapidly. Soon the settlement would disappear.

Dutka greeted me at the door wearing a truck driver's cap which hardly fit on his big round head. Everything about him was large and round. Although he tried to hide the fact by sporting a thin beard to give his face some shape.

We settled around the kitchen table on which his wife had laid out white bread, lunch meat and soda, and held hands and said grace. And the preacher added a special note of welcome as I was the first Jew to ever visit his home. It was a few days after Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin had been assassinated and curiously, that turned out to be the conversational ice-breaker.

The pastor expressed his condolences about the Israeli leader's death. Although he did question whether Rabin's policy of returning some land captured during the course of Israel's wars with the Arabs was wise. In fundamentalist Christian eschatology, Israel must exist in more or less its Biblical borders and Jews must return and be re-established in the land before the full fury of the end days, as described in the Book of Revelation, is released. After Armageddon, the last battle, is finished, Christ will return in judgment and the righteous will be borne up to Heaven and the wicked consigned for eternity to Hell.

I wondered what that meant for the Jews who had returned and he explained we would be given a second chance to acknowledge Jesus as the Messiah. I thought, well, if the end times really happen with all the violent weirdness in the Book of Revelation passing in front of my eyes I just might have to reconsider my view on whether Jesus is the promised one, but I kept that to myself.

"We're not reformation Christians," the preacher explained, "We are restoration Christians. We believe in restoring the Christian faith to the way it was at the time the Gospel was written, before the Catholic Church invented itself." In Dutka's church, there's no room for interpretation. The Bible is taken literally. His wife, in the deferential way required by their faith, said very little.

We spoke about politics. The couple’s greatest concern centred on the federal government's interference in education. Prayer was forbidden by the federal government in school. The Bible's views on creation were not taught, but Darwin's views on evolution were. They also believed there was a conspiracy to teach a new religion in the schools called “Secular Humanism”. It was a religion that put man's teachings above God's.

The fact that evolution is a scientific fact and the creation story in Genesis is not was not important to him. “Evolution’s what you believe.”

Well, no. There's a difference between truth and belief but in this part of America belief motivates action more than fact-based truth. The pastor believed the creation story should be taught as a scientific fact, he believed there was a religion called secular humanism and despite my being Jewish he was certain that’s what my faith really was.

From his pulpit he preached these beliefs and urged his flock to vote against secular forces by voting Republican, the one party that took a strong stand on moral issues. The preacher was young, in his early 30s, and his certainty was overpowering. I asked him if he did not look inside the deepest part of himself, his soul, and fear sometimes that he might be wrong. The man simply did not understand the question.

After lunch, the big guy took me down to his basement. His own little kingdom. In his office the walls were lined with posters: satirical drawings mocking Darwin's theory of evolution, charts showing the correct fundamentalist chronology of humanity's time on earth—6000 years, rather than several million. There was also a romantic recreation of a scene from the Civil War, the Battle Above the Clouds, a gallant Confederate defeat, on Lookout Mountain near Chattanooga, Tennessee.

In my mind the images and conversation ran together: heroism in the face of superior numbers; holding on to beliefs that are scorned, particularly up North; making Christian belief the basis for government policy; and the big man’s implacable certainty that his cause was right. It was the same toxic mix that led to rebellion in 1861.

"Do you get the sense you're fighting the Civil War all over?"

"Yes, only there won't be secession and there won't be war this time around. We'll fight through the political system, and this time we'll win."

Just after the polls closed that evening, the news came through that Kirk Fordyce, businessman and Christian, had won reelection easily. The next morning I headed South out of Tupelo on the Natchez Trace Parkway. Cotton McCullough had taken me this way a few days previously. He wanted to show me proof of how useless the federal government is. We turned off at the Troy Road, pulled onto the shoulder, and walked up a little knoll into some woods. There we found around a dozen stone grave markers.

A Union patrol, on a reconnaissance mission during the Civil War, had been ambushed by Confederate troops. They were buried where they fell, the weathered little markers their only memorial. Cotton's point was that for decades local organisations had petitioned Washington for some money to tidy up the site and make it into a proper memorial ground, after all these were their soldiers. That hadn't happened. In his mind it was just another example of the insensitivity of the federal government. We stood quietly, looking at the little markers. Cotton said "They died so far away, and their mommas and daddies never knew where they were buried."

I almost turned off again at the Troy Road. I thought I might pay private respects to the Union dead. But I just kept heading deeper into Mississippi, thinking of the words of the American philosopher George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” Santayana forgot to add,

“Those who remember the past too well are condemned to repeat it also.”

This has been the second chapter of Part Four of History of a Calamity, the story of how America went from Victory in World War 2 to Donald Trump and Cold Civil War in a single lifetime … Mine. The next chapter continues the journey around Mississippi in 1995, going from Philadelphia to Biloxi to Natchez and back to Clarksdale. Here’s a preview:

Sometimes, if you're lucky, you get a chance to confront your fears. Fear was on my mind when I chose to travel through Mississippi. I've travelled through most of the United States, but I had always avoided the place. My fear of Mississippi arose from a single incident; in June 1964, three civil rights workers were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi. James Chaney, a Black Mississippian, and Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman who were Northerners, from a background very similar to my own: white, middle class, liberal and Jewish.

And Philadelphia was my next destination.

And if you need to catch up on previous parts of my book, Part One, Bliss Was It In That Dawn, begins here:

Notes:

If ever there was a true statement regarding Southern thinking... "I asked him if he did not look inside the deepest part of himself, his soul, and fear sometimes that he might be wrong. The man simply did not understand the question."

"We may have lost the South for a generation" an un-sourced comment attributed to LBJ after signing the Civil Rights Act turns out to be insanely optimistic. Another excellent chapter Michael. I am always impressed (not jealous) of people able to interact with strangers in the way some journalists do. Your voice certainly identifies you as an outsider but I wonder if the interviews would have gone the same way if you had picked up a British accent with your move to the UK. (Everyone I have ever known who moved into the Old South found themselves fighting picking up an accent. Some without success.) LBJ's attributed quote "If you can convince the lowest white man he's better than the best colored man, he won't notice you're picking his pocket. Hell, give him somebody to look down on, and he'll empty his pockets for you" seems to me to be a defining point for much of the US. Americans claim to hate elites but we are very selective about who gets that attribution. And "States Rights" I love it. The Right is all for them until they control the federal government and then the States are expected to subservient to the Federal controls. Looking forward to the next chapter.