A DOUBLE FEATURE FOR AMERICA'S TROUBLED TIMES

Two Films, One Nearly 60 years old, Are Worth Re-watching

The History of America’s Calamity is sign posted with unlikely Hollywood films. Unlikely because they are so political and in many ways unpromising for the box office and yet, they get made.

If you want some psychological and historical insights into how and why a white supremacist mob attacked the Capitol in a vain attempt to invalidate the election you could spend a very profitable afternoon watching a double feature of Sidney Lumet’s “The Hill” and Konstantinos Costa-Gavras’ “Betrayed.” I will explain why but I have to warn you, there will be spoilers.

How far can people be pushed before they fight back?

The essential dilemma of modern liberalism is that it has tied itself to a very limited number of ways to respond to bullying and outright violence from its enemies. It’s a problem that has never been resolved. Surely sometimes you just have to fight back with the same level of aggression, don’t you?

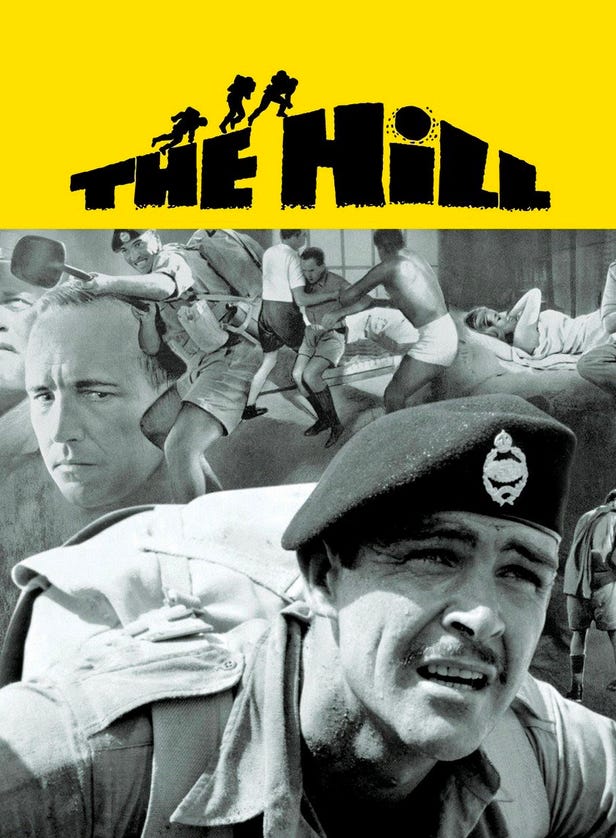

The Hill directed by Sidney Lumet is about that dilemma. I was not quite fifteen when the film came out in the summer of 1965. I went to see it at a matinee, not because of its political themes - I was not that politically precocious - but because it starred Sean Connery, “as you’ve never seen him before.” Connery was trying to free himself from the lucrative millstone of being James Bond, a part he had already played three times.

The film was like a two-hour long punch in the face. It wasn’t just Connery’s performance that shone although I came out of it aspiring to live up to his, “I don’t give a damn there’s nothing you can do to hurt me” masculinity.

The Hill, from a script by Ray Rigby, is set in a British military prison in North Africa during WW2. In the middle of the stockade is a massive hill of sand built by the prisoners as a form of punishment and when they break regulations they are forced to run up and down it in full kit and packs under the African sun until they drop.

Connery is an army lifer who ends up a prisoner because he no longer buys into the mind-numbing discipline of the military.

The place is run by the guards. Violent abuse is rife and the psychopath in chief is Staff Sgt. Williams played with sadistic gusto by Ian Hendry.

The system for preventing the pain and death being meted out by Hendry completely breaks down. The officers in charge of the prison are lazy and weak. But eventually they find their backbones and reform is on the way. The sadists are going to be relieved of duty.

Williams decides to give Connery one last beating. He is dragged off him by two of Connery’s cellmates and, out of shot, is heard being beaten himself, quite possibly to death. As Hendry shrieks in fear and pain, the camera focuses on Connery shouting at his comrades, “You’ll muck it up! Don’t punch him. We’ve Won!” His comrades don’t listen and out of shot we hear the man continuing to be beaten, quite possibly to death.

The fierce intensity of that moment burned itself into my adolescent mind. I found myself siding with those giving Hendry what he deserved. Why is Connery calling them off? Without some kind of justice delivered to the sadist, what victory have the men won?

It was a question I think embedded in the times. Outside the movie theatre the Civil Rights era was at its bloody height. Campaigners were being murdered helping African-Americans to vote down South. A few months before the film came out Sherriff Bull Connor unleashed dogs, water cannons and riot police on Martin Luther King and hundreds of non-violent protestors marching from Selma to Mongomery Alabama over the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Dr. King said, The arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice. But there are many corpses strewn along the way —including that of Martin Luther King— and murderers walk free. In the 60s we understood this was the problem of liberalism. The imperfect reach of justice in a power structure that is basically unchanged.

In 1965, the civil rights movement was about to split apart - even as the Voting Rights Act was about to become law - between those who wanted to continue with non-violent action and those who had taken enough blows and were demanding greater militancy. In my mind this echoed the split between Connery and his cellmates.

Sidney Lumet was a prodigiously prolific filmmaker. Making nearly a film a year for 40 years. His very best works were in one way or another about this dilemma of liberalism. All, one way or another, were about trying to work within the system, reform from within no matter the personal cost, or to strike out in violence. It was a dilemma the director faced in his own life.

Lumet began his career as a child actor. He made his Broadway debut in 1935 at the age of 11 in, “Dead End,” a slice of social realism about life in the New York slums. He continued to work as an actor until World War 2. Following Army service, he mustered out into the Age of American Victory, where New York was the world centre of culture, particularly theatre.

He inevitably hooked up with the Actors Studio shortly after it opened in 1947. So many of the people who had been part of his pre-war acting world - members of the Group Theatre - were part of the scene there.

The Actor’s Studio it has been repeated a thousand times was all about Stanislavski but it was also about much more. It was about a political and social esthetic and that esthetic had grown out of the social realism of the 1930s in response to the Great Depression.

Stanislavski’s technique trained actors to bring the “truth of life” to their performances. The truth of the Depression led many in the Group Theatre to political activism

In the years before the war many of the actors were involved in anti-fascist activities connected to the Communist party. And when the post-war communist witch hunts led by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House UnAmerican Activities Committee began in earnest, a lot of people connected to the Studio had problems.

Most prominent were the Studio’s founder, Elia Kazan, who directed the original production of Death of a Salesman, and Lee J. Cobb, who had originated the role of Willy Loman in that play. In 1951 Cobb was blacklisted for refusing to name names of people who might have been members of the Communist Party to HUAC. No one would hire him, in two years he went from creating one of the most important roles in 20th century theatre to unemployable and broke.

This was genuine “cancel culture.” Banks wouldn’t lend the actor money, friends had to be circumspect in seeing him because the FBI tailed Cobb wherever he went. His wife had a complete mental breakdown from the strain and had to be institutionalised.

Eventually Cobb named names, so did Kazan. Others didn’t. Lumet inevitably was caught up in the dragnet. He was not directly accused of Communist Party membership but was confronted by FBI agents looking for dirt on somebody else. Lumet remembered walking to the meeting thinking the career he had just got going was about to be taken away from him. But in the end nothing came of his interaction with the not so secret police.

And his career really was going well. There was a new medium for telling dramatic stories: television. And there were very few rules about what could or could not be done, except the rigours of the clock and making sure there was time for the commercial break. There were hours to fill and not a lot of programs to fill them with.

Lumet directed many different programs, including my favorite (when I was 6), “You Are There,” He often hired blacklisted writers if they were willing to work uncredited. And they did.

I wonder what impact living through the paranoid intensity of the McCarthy era had on Lumet’s sensibility. Surely, like Connery’s cell mates he must have wanted to physically confront the blacklist bullies.

But he didn’t and I wonder how surviving the witch hunts and building a thriving career shaped the way he told stories, how he directed his actors—and he was one of the greatest directors of actors in the history of cinema.

56 years after I first saw The Hill, in an America on fire —literally, the Watts riot in Los Angeles which would leave 14 people dead took place a few weeks after the film was released — I’m still thinking of Sidney Lumet and the dilemma of liberalism.

When the mob stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6 I couldn’t help but think it was inevitable, and if “liberals” over the last quarter century, as civility broke down in Congress and incitement on the airwaves in the world of right-wing talk radio and Fox News had been pushed back against with a fighter’s heart, perhaps America would not have reached this moment.

The thousands that attacked the Capitol were a disparate group but within the mob were well-armed and well-organized white supremacists from groups like the Oath Keepers dedicated to the violent overthrow of the US government and the creation of a white Christian government in its place.

This is not a new phenomenon. Periodically these groups spawn adherents who become terrorists in the cause of establishing this new government. Dylann Roof who murdered nine African Americans during a Bible study class at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston SC in 2015 is a recent example. Timothy McVeigh, who blew up the Alfred P. Murragh Federal Building in Oklahoma City OK in 1995 killing 168 people is the most notorious.

But even before McVeigh there was a dangerous sub-culture of white nationalist terrorists roaming rural America. Their presence was sufficiently well-known that they were the subject of Hollywood thriller in 1988, Betrayed, directed by Greek-French filmmaker, Costa-Gavras, and written by journalist turned screenwriter, Joe Eszterhas.

The pair were a match made in political melodrama heaven. Subtlety in story-telling was neither’s style and both had interesting daddy issues going back to the second world war.

Costa-Gavras’s father had been a member of a band of Greek communist partisans and in the years after the war, as the West and the Soviet Union vied for control of the Balkans stoking a civil war in Greece, Costa-Gavras’s father had been imprisoned. The director was sent to France where he completed his education and became a filmmaker specializing in political thrillers like the double Oscar nominated “Z.” (it won for Best Foreign Language film) And “Missing” about the murder of American Charles Horman during the military coup that overthrew the freely elected socialist government of Salvador Allende in Chile (Costa-Gavras won a second oscar for his screenplay).

Eszterhas’s father was a Hungarian journalist before and during the war who had written anti-Semitic propaganda. He was an earnest collaborator with the Nazi occupation, something he neglected to mention when he applied to come to the US immediately after the war. More than 560,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered during the Holocaust. Eszterhas claims not to have known about his father’s history until just after he finished writing the script for Betrayed.

That’s an interesting claim since the film opens with the murder of a Jew. Specifically, a Jewish liberal talk radio host. The scene is based on the real life murder of Alan Berg, a Denver talk show host. It’s an incident long-forgotten but probably shouldn’t be. In 1984, Berg was gunned down by members of The Order, a neo-Nazi group led by a man named Robert Mathews.

Ultimately Berg’s murder led to an FBI investigation, a shoot-out in which Matthews was killed, and ten of the group’s members were imprisoned under RICO statutes.

A good thriller could have been made from these facts but that’s not Hollywood’s style. There has to be a love story. In Betrayed, the character based on Mathews is played by Tom Berenger and he is brought down by an FBI undercover agent, Debra Winger, who gets a little too close for comfort. Their sexual chemistry managed to obscure the fact that Berenger is a genuine Nazi.

The film’s tension is ratcheted up in a scene—wholly invented—in which Berenger and his followers capture a Black man, take him out to an area of empty fields, give him a gun and a head start and then track him down and kill him.

The film didn’t do particularly well at the box office. The man hunting scene, and the love story, had critics rolling their collective eyes.

Roger Ebert wrote in the Chicago Sun-Times:

It is reprehensible to put a sequence like that in a film intended as entertainment, no matter what the motives of the characters or the alleged importance to the plot. This sequence is as disturbing and cynical as anything I’ve seen in a long time - a breach of standards so disturbing that it brings the film to a halt from which it barely recovers.

Rita Kempley in the Washington Post wrote:

It's Nazi Germany all over again, banal as ever and inflamed by recession. There's no logic to the supremacists' thinking, only unreasoning hatred, the need to protect their purity, to cleanse the land. Gary and the others act in "self-defense."

Kempley’s paragraph is the one that resonates today. There isn’t a thing in that description of the fictional characters in this potboiler of a movie that hasn’t been written about the real-life white supremacists who roamed the Capitol armed and looking for Democratic legislators to kill.

The ones willing to kill were a minority of the mob although what percentage is hard to calculate. Anyway, when you’re locked and loaded and marauding with intent your presence shouldn’t be measured in percentages.

By the time the film came out I had left the United States for Britain and was freelancing as an arts reporter. I often reviewed American themed films for BBC Radio’s daily arts show, Kaleidoscope, and a producer sent me to see Betrayed. My memory is the studio discussion raised the same questions about plausibility that Ebert, Kempley and others did.

I accepted the film’s flaws but not the possibilities that it described. I know that there is a world that might exist beyond my urban liberal imaginings. America is a huge country with such disparities of experience that it’s almost impossible for people living a rural life in a community that is exclusively white to have any idea of what life is like in one of America’s cosmopolitan cities … and vice versa.

And as for the man-hunt sequence: I didn’t think it was cynical. I was aware even in 1988 that Black men simply go missing in America, mostly for economic reasons or they are imprisoned and removed from their communities. It didn’t seem implausible in a country where lynchings occasionally continued that an African-American male, on his own, detached from his community and all other social connections, might be murdered by a gang who shared the beliefs of The Order. Who would know? Who would care?

People in America’s cities for too long ignored the reaction to the civil rights movement that has been a primary feature of American politics since 1968. That resentment took over the Republican Party long ago. Ronald Reagan campaigned on it and won the White House. Generations have been brought up in it.

There has long been a refusal by people in the main population centers to see the violent white Christian rage which is the nuclear fuel at the core of the GOP. People filled with this rage are willing to murder talk show hosts and women’s health care providers and Black worshippers in the midst of their Bible study class on a weekday evening. They drag young gay men out of town, bend their bodies over barbed wire fences and slowly beat them to death.

This violence has been going on for decades. If you look beyond Betrayed’s flaws, the message of this 1988 film was loud and clear: These white supremacist groups are a danger to the American body politic. Root them out.

Thanks for reading this far. Please leave a comment and let me know what you think. Agree, disagree (but politely!) add some of your knowledge … and I will respond. Please tell your friends about History of a Calamity. Better yet, invite them to subscribe as well.

As a 14 yr old I stood in Duke St in Derry on the afternoon of Oct 5th 1968. Despite being behind the police line, (very few were in front of it) I still found myself fleeing across Craigavon bridge with a water cannon hard on my heels. Your article may be a necessary light on American society but so much of it resonates in Ireland and no doubt many other countries.

The dilemma of how one fights fire is pivotal to an individual's disposition. Do you choose to fight something with itself but bigger stronger or with its opposite; fire with water, heat with cold, anger with calm, rudeness with politeness? On the other hand, as a friend once explained to me when I asked why no one was rude to her: "When people bark at me i bite, they tend not to bark again."

To finish, it was the great Republican (irish) Terance McSweeney who said "It is not those who can inflict the most but those who can endure the most, who will conquer." Something the Republican movement forgot.

What a delightful read!